DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.18401Published:

2022-08-22Issue:

Vol. 24 No. 2 (2022): July-DecemberSection:

Research ArticlesEmotions Experienced by Secondary School Students in English Classes in Mexico.

Emociones experimentadas por estudiantes de secundaria en clases de inglés en México

Keywords:

achievement emotions, foreign language learning, secondary school students (en).Keywords:

emociones de logro, aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras, estudiantes de secundaria (es).Downloads

References

Abdullah, M. C., Elias, H., Mahyuddin, R., & Uli, J. (2004). Emotional intelligence and academic achievement among Malaysian secondary students. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 19(3-4), 105-121. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=9346962414930394898&hl=es&as_sdt=0,5

Csizér K., Albert Á., & Piniel K. (2021). The interrelationship of language learning autonomy, self-efficacy, motivation and emotions: The investigation of Hungarian secondary school students. In M. Pawlak (Ed.), Investigating Individual Learner Differences in Second Language Learning (pp. 1-21). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75726-7_1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75726-7_1

Barcelata, B., Durán C. & Lucio, E. (2004). Indicadores de malestar psicológico en un grupo de adolescentes mexicanos. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 13, 64-73. https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/psicologia/article/view/1210/1762

Becerril, I. (2015, April 27). En México sólo 5% de la población habla inglés: IMCO. El financiero. http://www.elfinanciero.com.mx/economia/en-mexico-solo-de-la-poblacion-habla-ingles-imco.html

Bieleke, M., Gogol, K., Goetz, T., Daniels, L., & Pekrun, R. (2021). The AEQ-S: A short version of the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 65, 101940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101940 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101940

Boekaerts, M. (2007). Understanding students’ affective processes in the classroom. In P. Schutz, R. Pekrun, & G. Phye (Eds.), Emotion in Education (pp. 37-56). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012372545-5/50004-6 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012372545-5/50004-6

Buenrostro-Guerrero, A. E., Valadez-Sierra, M. D., Soltero-Avelar, R., Nava-Bustos, G., Zambrano-Guzmán, R., & García-García, A. (2012). Inteligencia emocional y rendimiento académico en adolescentes. Revista de Educación y Desarrollo, 20(1), 29-37. https://www.cucs.udg.mx/revistas/edu_desarrollo/anteriores/20/020_Buenrostro.pdf

British Council (2015, May). English in Mexico: An examination of policy, perceptions and influencing factors. https://ei.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/latin-america-research/English%20in%20Mexico.pdf

Clem, A. L., Rudasill, K. M., Hirvonen, R., Aunola, K., & Kiuru, N. (2021). The roles of teacher-student relationship quality and self-concept of ability in adolescents’ achievement emotions: Temperament as a moderator. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 36(2), 263-286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00473-6 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-020-00473-6

Coutinho dos Santos, J., Veiga de Souza, V., & Vélez-Ruiz, M. (2020). Evaluación de las emociones que impiden que estudiantes ecuatorianos hablen inglés en clase: Caso Provincia de Los Ríos. Maskana, 11(1), 5-14. https://doi.org/10.18537/mskn.11.01.01 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18537/mskn.11.01.01

Cheng, L., Klinger, D., Fox, J., Doe, C., Jin, Y., & Wu, J. (2014). Motivation and test anxiety in test performance across three testing contexts: The CAEL, CET and GEPT. TESOL Quarterly, 48(2), 300-330. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.105 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.105

Cheng, Y. S. (2017). Development and preliminary validation of four brief measures of L2 language-skill-specific anxiety. System, 68, 15-25.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.06.009 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2017.06.009

de Prada, E. (1993). Aspectos psicolingüísticos del aprendizaje de una lengua extranjera. Universidad de Santiago de Compostela: Servicio de Publicaciones e Intercambio Científico.

Dewaele, J-M., & MacIntyre, P. (2014). The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 4(2), 237-274. http://dx.doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.5 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.5

Dewaele J-M., Witney J., Saito K., & Dewaele L. (2018). Foreign language enjoyment and anxiety: The effect of teacher and learner variables. Language Teaching Research, 22(6), 676-697. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817692161 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817692161

Duarte-Melgarejo, G. E. (2014). Influencia de las estrategias pedagógicas en las emociones académicas que afectan negativamente el desarrollo de habilidades de comprensión de lectura y análisis literario en una lengua extranjera [Master’s thesis, Universidad de los Andes]. https://repositorio.uniandes.edu.co/handle/1992/12798

Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2003). La inteligencia emocional en el contexto educativo: hallazgos científicos de sus efectos en el aula. Revista de Educación, 332, 97-116. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/dam/jcr:6b5bc679-e550-47d9-804e-e86b8f4b4603/re3320611443-pdf.pdf

Flores, Z. (2017, January 31) Superan salarios en EU seis veces los de México. El Financiero. http://www.elfinanciero. com.mx/economia/superan-salarios-en-eu-seis-veces-los-de-mexico.html

Ganotice, F. A., Datu, J. A. D., & King, R. B. (2016). Which emotional profiles exhibit the best learning outcomes? A person-centered analysis of students’ academic emotions. School Psychology International, 37(5), 498-518. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316660147 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316660147

Granada-Páez, D. C. (2021). Espacios lúdicos en la clase de inglés que favorecen el desarrollo de emociones y habilidades comunicativas [Undergraduate thesis, Fundación Universitaria Los Libertadores]. https://repository.libertadores.edu.co/handle/11371/3816

Hamideh, T., Firooz, S., Mohammad, S. B., & Mohammad, B. (2020). Investigating the relationship between Iranian EFL learners’ use of language learning strategies and foreign language skills achievement, Cogent Arts & Humanities, 7(1), 1710944.

https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2019.1710944 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2019.1710944

Horwitz, E. K. (2017). On the misreading of Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope (1986) and the need to balance anxiety research and the experiences of anxious language learners. In C. Gkonou, M. Daubney, & J.-M. Dewaele (Eds.), New Insights into Language Anxiety: Theory, Research and Educational Implications (pp. 31-47). Multilingual Matters. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783097722-004

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70, 125-132. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586302 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x

King, R. B. (2010). What do students feel in school and how do we measure them? Examining the psychometric properties of the S-AEQ-F. Philippine Journal of Psychology, 43(2), 161-176. https://www.academia.edu/1133678/What_do_students_feel_in_school_and_how_do_we_measure_them_Examining_the_psychometric_properties_of_the_S-AEQ-F

King, R. B., & Areepattamannil, S. (2014). What students feel in school influences the strategies they use for learning: Academic emotions and cognitive/meta-cognitive strategies. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 8(1), 18-27. https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2014.3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/prp.2014.3

MacIntyre, P., & Vincze, L. (2017). Positive and negative emotions underlie motivation for L2 learning. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 7(1), 61-88. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2017.7.1.4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2017.7.1.4

MacIntyre, P. D. (2017). An overview of language anxiety research and trends in its

development. In C. Gkonou, M. Daubney, & J.-M. Dewaele (Eds.), New Insights

into Language Anxiety: Theory, Research and Educational Implications (pp. 11-30).

Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783097722-003 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783097722-003

Martín-Velásquez, O. (2019). La influencia del componente emocional en el aprendizaje del inglés [Master’s thesis, Universidad de la Laguna]. http://riull.ull.es/xmlui/handle/915/17307

Martinenco, R. M., Vaja, A. B., & Martín, R. B. (2020). Emociones académicas en una secuencia didáctica de Lengua y Literatura en Educación Secundaria. Quaderns de Psicología, 22(1), e1495. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.1495 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.1495

Mendelson, R. A., Mantz, T., Guity, F., & Mendelson, R. (2016). The role of emotional intelligence in the academic achievement of Latin American Students in secondary school. Journal of Academy of Business and Economics, 16, 53-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.18374/JABE-16-2.6 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18374/JABE-16-2.6

Méndez-López, M. G. (2011). The motivational properties of emotions in Foreign Language Learning. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 13 (2), 43-59. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.3764 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.3764

Méndez-López, M. G. (2012). The emotional experience of learning English as a foreign language: Mexican ELT students’ voices on motivation. Manda Editores.

Méndez-López, M. G., & Peña-Aguilar, A. (2013). Emotions as learning enhancers of Foreign Language Learning motivation. PROFILE Journal, 15(1), 109-124. Retrieved from https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/profile/article/view/37872

Méndez-López, M. G., & Fabela-Cárdenas, M. (2014). Emotions and their effects in a language learning Mexican context. System 42 (2), 298-307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.12.006 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.12.006

Méndez-López, M. G. (2015). Emotions reported by English language teaching major students in Mexico. UQROO.

Noor H. R. (2019). Cycle of fear in learning: The case for three language skills. American Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 4(1), 151-162. https://doi.org/10.20448/801.41.151.162 DOI: https://doi.org/10.20448/801.41.151.162

Oga-Baldwin, W. L. Q. (2019). Acting, thinking, feeling, making, collaborating: The engagement process in foreign language learning. System, 86, 102128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.102128 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.102128

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2015). Programme for international student assessment (PISA): Results from PISA 2015. http://www.oecd.org/pisa/PISA-2015-Mexico.pdf

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2021). Youth not in employment, education or training (NEET).

https://doi.org/10.1787/72d1033a-en DOI: https://doi.org/10.1787/72d1033a-en

Ovejas, I. S. (2020). La socialización diferencial emocional de género como factor predictor del carácter. IQUAL. Revista de Género e Igualdad, (3), 80-93. https://doi.org/10.6018/iqual.369611 DOI: https://doi.org/10.6018/iqual.369611

Paoloni, P., Vaja, A., & Muñoz, V. (2014). Reliability and validity of the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire. A study of Argentinean university students. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 12(3), 671-692. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2931/293132659006.pdf

Pekrun, R. (2017). Emotion and achievement during adolescence. Child Development Perspectives 11, 215-221. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12237 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12237

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., & Perry, R. P. (2006). Academic Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ) – User’s manual. University of Munich: Department of Psychology.

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., Barchfeld, P., & Perry, R. P. (2011). Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 36-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.002 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.10.002

Piniel, K., & Albert, A. (2018). Advanced learners’ foreign language-related emotions across the four skills. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 8(1), 127-147. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.1.6 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.1.6

Shao, K. Q., Loderer, K., Symes, W., & Pekrun, R. (2019). Achievement emotions in second language learning: Validating the achievement emotion Questionnaire. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.102121

(Learning-related) in a Chinese EFL context. Unpublished manuscript.

Ramírez-Romero, J. L., Sayer, P., & Pamplón-Irigoyen, E. N. (2014). English language teaching in public primary schools in Mexico: The practices and challenges of implementing a national language education program. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 27(8), 1020-1043. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2014.924638 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2014.924638

Reilly, P., & Sánchez-Rosas, J. (2019). The achievement emotions of English language learners in Mexico. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 16(1), 34-48. http://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/v16n12019/reilly.pdf

Retana-Alvarado, D. A., Camacho-Álvarez, M. M., Osborne-Rovira, A., Vázquez-Bernal, B., Jiménez-Pérez, R., & de las Heras-Pérez, M. Á. (2018). Emociones de estudiantes costarricenses de secundaria respecto al desarrollo de un proyecto de indagación según el género. In C. Martínez-Losada & S. García-Barros (Eds.), Iluminando el cambio educativo (pp. 1289-1294). Universidad de la Coruña, Servicio de Publicaciones.

Rivera-Ruseria, I. P. (2021). La relación entre los niveles de ansiedad con la enseñanza socioemocional en estudiantes del nivel A1 en una academia de idiomas. https://ciencia.lasalle.edu.co/maest_didactica_lenguas/20.

Rodríguez-Pérez, N. (2014). Creencias y representaciones de los profesores de lenguas extranjeras sobre la influencia de los factores motivacionales y emocionales en los alumnos y en las alumnas. Porta Linguarum, 21, 183-197. http://hdl.handle.net/10481/30490 DOI: https://doi.org/10.30827/Digibug.30490

Román-Leal, E., & García-Pérez, J. A. (2020). Efecto del tipo de sesión y del estilo de enseñanza sobre las emociones del alumnado de educación secundaria. EmásF: Revista Digital de Educación Física, 11(62), 27-41. http://emasf.webcindario.com

Saito, K., Dewaele, J.-M., Abe, M., & In'nami, Y. (2018), Motivation, emotion, learning experience, and second language comprehensibility development in classroom settings: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Language Learning, 68, 709-743. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12297 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12297

Sayer, P. (2015). More & earlier: Neoliberalism and primary English education in Mexican public schools. L2 Journal 7(3), 40-56. https://doi.org/10.5070/L27323602 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5070/L27323602

Taheri, H., Sadighi, F., Sadegh Bagheri, M., & Bavali, M. (2019). EFL learners’ L2 achievement and its relationship with cognitive intelligence, emotional intelligence, learning styles, and language learning strategies. Cogent Education, 6(1), 1655882.

https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2019.1655882 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2019.1655882

Tapia, M. & Marsh, G. E. (2006). The effects of sex and grade point average on emotional intelligence, Psicothema, 18, 108-111. Recuperado a partir de https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/8428

Teimouri, Y. (2018). Differential roles of shame and guilt in L2 learning: How bad is bad? The Modern Language Journal, 102(4), 632-652. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12511 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12511

Trigoso, M. (2013). Inteligencia emocional en jóvenes y adolescentes españoles y peruanos: variables psicológicas y educativas [Doctoral thesis, Universidad de León]. https://buleria.unileon.es/bitstream/handle/10612/3344/Inteligencia_emocional.PDF

Valadez, D., Pérez., L. & Beltrán, J. (2010). La inteligencia emocional de los adolescentes. Faisca, 15(17), 2-17.

Villavicencio, F. T., & Bernardo A. B. I. (2013). Positive academic emotions moderate the relationship between self-regulation and achievement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83, 329-340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02064.x DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02064.x

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 26 de agosto de 2021; Aceptado: 16 de junio de 2022

Abstract

This study examined the frequency of emotions experienced by 845 (F = 448, M = 397) secondary school students in the city of Veracruz, Mexico, who self-reported their experience of eight emotions included in the reference framework by Pekrun et al. while attending English as foreign language classes. The students answered the short version of the academic emotions questionnaire for Filipinos (S-AEQ-F), with the results revealing a higher frequency of hope, pride, and enjoyment, while hopelessness, anger, and boredom were reported with lower frequency levels. Although the students seem to have experienced the same emotions, a statistical difference was found for the experience of pride, anxiety, and shame by female learners. The results also indicate that female students self-reported being more proficient in English than their male counterparts. Female participants self-reported higher grades than their male counterparts, a surprising result, given that, although they reported more pride, shame, and anxiety, they also reported higher levels of achievement in English. The results of the study and its implications for language learning are also presented.

Keywords

emotions, foreign language learning, secondary school students, Mexico.Resumen

Este estudio examinó la frecuencia de emociones de 845 (F = 448, M = 397) estudiantes de secundaria en la ciudad de Veracruz, México, quienes autorreportaron su experiencia de ocho emociones incluidas en el marco referencial de Pekrun et al. mientras asistían a clases de inglés como lengua extranjera. Los estudiantes respondieron la versión corta del cuestionario de emociones para filipinos (S-AEQ-F), cuyos resultados revelaron una mayor frecuencia de esperanza, orgullo y disfrute, mientras que la desesperanza, la ira y el aburrimiento fueron reportados con niveles de frecuencia más bajos. Aunque parece que los estudiantes experimentaron las mismas emociones, se encontró una diferencia significativa en la experiencia de orgullo, ansiedad y vergüenza por parte de las alumnas. Los resultados también indican que las alumnas declararon ser más competentes en inglés que los alumnos. Las participantes autorreportaron calificaciones más altas que sus compañeros, un resultado sorprendente, dado que, aunque reportaron más orgullo, vergüenza y ansiedad, también reportaron niveles más altos de competencia en inglés. Se presentan, además, los resultados del estudio y sus implicaciones para el aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras.

Palabras clave

emociones, aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras, estudiantes de secundaria, México.Introduction

The emotions experienced when learning, specifically when learning a foreign language, are a subject that needs to be explored in order to better understand how they affect the interest and motivation shown by students in the classroom. In Mexico, English language proficiency is crucial not only for academic purposes, but also for employment. English as a foreign language (EFL) is a required subject from primary school to undergraduate degree programs, wherein students need to show a proficient English level in order to graduate, and said proficiency is useful for obtaining a well-paid job (Becerril, 2015). However, few Mexicans have a high English proficiency, with the British Council (2015) finding that only 14% of Mexicans can speak fluent English. A lack of English language skills affects the number of Mexicans that can access well-paid employment and a good quality of life, with a monolingual Spanish-speaker earning an approximate 290 dollars per month on average (Flores, 2017).

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2015), Mexican secondary school students rank very low in terms of academic achievement in different academic subjects. Thus, an exploration of the emotional experience of 11- to 15-year-olds in foreign language classes is important because emotions are a crucial element of the language learning process (Piniel and Albert, 2018). Emotions such as enjoyment and anxiety have been linked to the use of higher-level learning strategies, which have been found to lead to better results in academic subjects in general (Clem et al., 2021. Pekrun, 2017 ) and in language classes specifically (Abdullah et al., 2004. Oga Baldwin, 2019).

The English language has been taught at the secondary school level for over 60 years in Mexico. Despite this long history, Mexican learners have historically achieved poor levels of English language proficiency ( Sayer, 2015 ). While EFL is taught in private schools, starting at kindergarten, it was not taught in Mexican state primary schools until the National Program for English in Basic Education was introduced by the Ministry of Education in 2009 (Ramírez-Romero et al., 2014). The objective of this program was that, by the end of ninth grade, Mexican students would have received 360 hours of instruction, which would place them at a B1 level as per the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001).

Research suggests that unpleasant emotions are associated with lower academic performance (Extremera and Fernández-Berrocal, 2003) and school desertion among Latino students (Mendelson et al ., 2016), which is why it is of the utmost importance to determine the type of emotions most experienced by secondary school students in Mexico when studying English. The OECD found poorer academic performance in females than in males in different academic subjects, so it is relevant to compare the emotions experienced by these while learning English at the secondary school level. The high-school learning experience exerts an influence not only on females’ access to learning opportunities, but also on the completion of a bachelor’s degree, employment, and quality of life (Becerril, 2015. Flores, 2017. Mendelson et al ., 2016). Thus, this study aims to explore the emotions experienced by secondary school students in Veracruz, Mexico, in order to provide insights into the emotional experience of young Mexican people.

Emotions in language learning

Research has explored emotions over the past decade in an effort to understand how they affect student interest and motivation in EFL classrooms. Various studies have shown that students experience a wide range of positive and negative emotions in the classroom, such as enjoyment, pride, anxiety, and fear (Coutinho dos Santos et al., 2020. Méndez-López, 2011. Rivera-Ruseria, 2021 ). Positive emotions are essential for language learning, with various studies reporting the benefits of this type of emotion, which lead to action tendencies that favor language learning (Shao et al., 2019), cause students to focus on the task at hand ( Pekrun, 2017 ), boost self-efficacy judgments, and reduce ego-protective behaviors ( Boekaerts, 2007 ). While positive emotions are generally favorable for language learning (Dewaele et al., 2018. MacIntyre and Vincze, 2017), experiencing solely positive emotions can undermine a students’ level of effort ( Pekrun, 2017 ).

In Mexico, studies conducted on the emotions experienced by secondary school language learners are scant; the ones developed have only involved university students ( Méndez-López, 2011, 2015, 2015. Reilly and Sánchez-Rosas, 2019). Dewaele and MacIntyre (2014) surveyed 1746 language learners around the world regarding their experience of enjoyment and anxiety. They found that learners reported experiencing enjoyment more frequently than anxiety. Joy was experienced during specific classroom activities (i.e., role plays, debates, and games) and because of peer recognition. Although the participants’ ages ranged from 11 to 75, the teenagers surveyed revealed more anxiety than any other age group in the sample. Latin American participants described enjoying their language classes at the same rate as European or Arab students. Concluding that “enjoyment might be the emotional key to unlocking the language learning potential of adults and children alike” (Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2014, p. 261), the study found that the bonds built by laughter and enjoyment in a language class result in improved learning and higher levels of achievement.

In Spain, Román-Leal and García-Pérez, (2020) conducted a study with 130 secondary students. Participants reported the emotions experienced in class, as well as their intensity. The results showed that students reported more positive than negative emotions, and that the intensity of said positive emotions was greater with class activities in which they worked individually or in groups. On the contrary, negative emotions were reported when classes were dominated by the teacher, without active participation by students. Thus, these results provide evidence that activities in which students are completely involved are more likely to increase not only positive emotions, but also their interest and motivation in class.

In a recent study, Martín-Velásquez (2019) carried out an intervention in secondary English classes in order to increase the experience of positive emotions by Spanish students. 56 secondary students of first, second, and third grade performed humanistic activities in order to better their intra and interpersonal relationships, so they could increase their interest, motivation, and level of achievement in the EFL classroom. The results obtained showed that the students were motivated and interested in class since the classroom climate improved, as well as their relationship with teachers. This led them to exhibit active participation as well as respect and empathy towards their classmates. Thus, the experience of positive emotions in language classes improves not only participation and interest in the language class, but also promotes a better relationship with teachers, thus enhancing the learning environment.

Negative emotions, in contrast to that discussed above, have been reported to be detrimental to language learning. Since the first studies conducted on anxiety in language learning (Horwitz et al., 1986), negative emotions have been considered unfavorable to the language learning process. Although some studies have reported that students may experience facilitative or debilitative anxiety, most research has reported a negative correlation between anxiety and language learning ( Cheng, 2017. Dewaele et al., 2018). Negative emotions distract attention, cause poor performance in the target language, affect attention spans, and restrict learners’ thinking and performance, among other consequences (Cheng et al ., 2014. Taheri et al., 2019). Negative emotions are experienced in language classrooms due to factors as diverse as the difficulty level, the teaching style, the teacher’s attitude, self-esteem, motivation, the grading system used by the teacher, or fear of speaking in the target language or of mockery by peers (Méndez-López and Fabela-Cárdenas, 2014. Noor, 2019).

Coutinho dos Santos et al. (2020) studied the emotions that block Ecuadorian students while speaking in English classes. Through observations, questionnaires, interviews, and a visual narrative, the researchers found that the fear of making mistakes, the fear of being judged, shyness, the lack of confidence, and anxiety are the negative emotions that inhibit students to participate in speaking activities in class. They found that fear of being judged and of making mistakes were more common in women, whereas anxiety was most reported by male students. The scholars concluded that women were more likely to experience negative emotions in class than men.

Retana-Alvarado et al. (2018) examined the intensity of the emotions experienced by 159 secondary students in Costa Rica. The students self-reported their emotional experience using a questionnaire that included 14 emotions (seven positive and seven negative). They reported experiencing more positive than negative emotions, which is in line with previous studies in different contexts. Female students reported greater intensity on the expression of positive and negative emotions, which may show their willingness to express their emotions openly. Regarding negative emotions, the results of the study showed that, while men students tend to experience frustration, boredom, and anger with greater intensity, female students reported experiencing stress and fear with greater intensity.

In a study conducted with Colombian students, Granada-Paéz (2021) found that participants reported experiencing insecurity, fear, anger, and anguish. Very few students reported feeling enthusiasm or any other positive emotion. The researcher implemented an intervention involving

ludic activities in order to increase the experience of positive emotions in English classes. According to Granada-Paéz (2021), the inclusion of ludic activities helped students to express their feelings and concerns, as well as to propose and build knowledge with their peers and teachers.

Ludic activities, together with a humanistic approach, have proven to be beneficial not only for the class environment, but also for the learning process (Granada-Paéz, 2021).

Teimouri (2018) examined, via two studies, the guilt and shame experienced by foreign language learners, as well as the effect of these emotions on motivation and performance. The first study applied a questionnaire with 86 language learners studying in private institutions in Iran, while 112 students from different private institutions participated in the second study. The results obtained showed that shame inhibits foreign language learners’ willingness to communicate in the classroom and hinders their attention in classroom tasks or activities, whereas guilt was an emotion that motivated students to perform actions in order to correct their failures in a specific task or activity. Negative feelings of regret and remorse encourage learners to look for ways to improve their target language performance. This corroborates the findings reported by MéndezLópez (2012), in that negative emotions experienced in a humanistic environment stimulate learners’ development, thus leading them, after a period of reflection, to seek learning strategies that improve their performance in English. As suggested by MacIntyre and Vincze (2017), some negative emotions experienced alongside multiple positive ones may be beneficial for language learning, as they can encourage reflection and action that will improve the process.

This study aims to contribute to the current knowledge on the role played by emotions in the process of learning English as a foreign language at the secondary school level, via the examination of the following research questions:

1. What emotions are most frequently experienced by secondary school students in Mexico in their English language classes?

2. What are the differences regarding the emotional experience of female and male students in secondary school English language classes in Mexico?

3. What are the differences regarding the level of achievement of female and male students in secondary school English language classes in Mexico?

To date, studies identifying the emotions experienced by secondary school students in the State of Veracruz cannot be found. This study will therefore be the first to explore said emotions in the State, as well as their relationship with gender and achievement. It has been reported that female secondary students are more prone to experience negative emotions than males (Coutinho dos Santos et al ., 2020), which may lead female students to perceive the learning of a foreign language as difficult and block not only their access to the university, but also to employment and a better quality of life. Thus, it is paramount to understand the emotions experienced by Mexican secondary students while learning English, so that help may be provided in managing them.

Method

This study applied a quantitative design in order to identify the most frequent emotions experienced by secondary school students in Mexico, developing a questionnaire with the aim to provide answers to the stated research questions and collecting quantitative data from students from all three grades at four public secondary schools in the city of Veracruz.

Participants

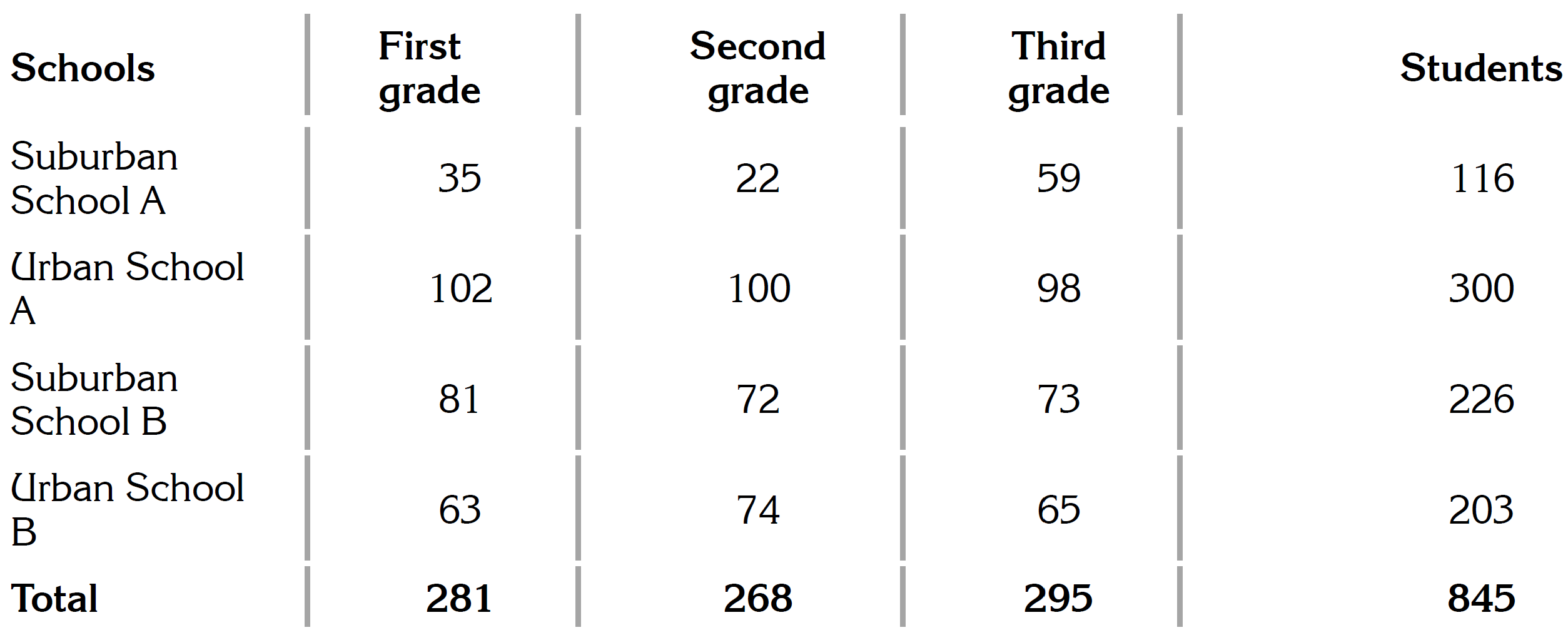

This study selected 845 students from the first, second, and third grades at schools in two urban and two suburban areas (116 students from Suburban School A, 300 from Urban School A, 226 from Suburban School B, and 203 from Urban School B). Prior to the collection of data, consent to conduct the study during classroom hours was obtained from the principals and teachers of the selected schools.

As shown in Table 1 , the total number of respondents was 845 (F = 448, M = 397), and their ages ranged from 11 to 15 years old (mean = 13.43, SD = 1.01). Out of the 845 students, 295 (35.03%) were in third grade, 268 (32.19%) were in second grade, and 281 (32.78%) were in first grade.

Instrument

The control-value theory by Pekrun et al. (2006) classifies emotions according to three dimensions: valence (positive or negative), activation level (activating or deactivating), and focus (activities or products). Pekrun et al. (2011) developed this theory into the Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ), which includes 24 scales measuring enjoyment, hope, pride, relief, anger, anxiety, shame, hopelessness, and boredom. Items in the AEQ measure said emotions in relation to classes, studying, and sitting exams, as these are the activities that trigger more emotions in educational contexts.

Table 1: Participants from the four secondary schools

The AEQ has also been used in different studies to measure foreign language students’ emotions while learning English (Shao et al., 2019). The validity and reliability of the instruments developed based on the AEQ have been demonstrated in various articles (King, and Areepattamannil, 2014. Pekrun et al., 2011. Shao et al., 2019). This study used the S-AEQ-F, which is another adaptation of the AEQ ( King, 2010 ) and includes 16 items measuring three positive (enjoyment, hope, and pride) and five negative emotions (anger, anxiety, boredom, hopelessness, and shame). Studies worldwide have provided evidence that the S-AEQ-F is a valid and reliable instrument (Bieleke et al ., 2021. Paoloni et al., 2014. King, 2010. King and Areepattamannil, 2014).

Data collection

The data were collected by means of the S-AEQ-F questionnaire ( King, 2010 ) during regular school days, with participants responding on a fourpoint Likert scale, with a score of four indicating a high frequency of experiencing the emotion and a score of one indicating no experience of the emotion. The data were gathered in Spring 2019 by four researchers, with the items translated into Spanish in order to aid the secondary school students’ comprehension (see Appendix 1).

Data analysis

The data extracted from the completed questionnaires were analyzed using the SPSS 23 software package, wherein the means for each emotion and the averages for the three positive and five negative emotions were calculated, and the differences were then tested for significance using paired t-tests. Moreover, the differences in the emotions reported by males and females, as well as high and low achievers, were compared using independent-samples t-tests. Low achievers were classified as those who self-reported usual grades of 70% or below in English class, while high achievers were those who self-reported grades of 71% or above. The alpha level for the t-tests was set at 0.01 in order to address the problem of multiple comparisons.

Results

Descriptive statistics were performed by comparing the mean frequency ratings of the eight emotions included in the S-AEQ-F questionnaire in order to answer the first research question.

In Table 2 , the results obtained show that the three most frequently experienced emotions are pride (M = 3.33), hope (M = 3.00), and enjoyment (M = 2.89), while the least experienced ones are hopelessness (M = 1.47), anger (M = 1.61), and boredom (M = 1.70). This indicates a general tendency towards experiencing more positive than negative emotions while learning English at secondary schools in Veracruz, which is consistent with previous studies conducted in international contexts, in which language learners have been found to experience more enjoyment than anxiety in their classes (Csizér et al., 2021. Rivera-Ruseria 2021. Saito et al., 2018).

Table 2: Frequency of emotions experienced by secondary school students

Number

Min.

Max.

Mean

Standard deviation

1. Pride

845

1.00

4.00

3.3337

0.71369

2. Hope

845

1.00

4.00

3.0012

0.75374

3. Enjoyment

845

1.00

4.00

2.8994

0.77003

4. Anxiety

845

1.00

4.00

2.0284

0.78668

5. Shame

845

1.00

4.00

1.8408

0.88520

6. Boredom

845

1.00

4.00

1.7059

0.69713

7. Anger

845

1.00

4.00

1.6148

0.66288

8. Hopelessness

845

1.00

4.00

1.4751

0.63187

Valid number

845

The most experienced negative emotion was anxiety (M = 2.02), a finding in line with the results of previous studies, which have revealed anxiety to be the negative emotion undergone by all learners during the process of learning a second or foreign language (Coutinho dos Santos et al ., 2020. Horwitz, 2017. MacIntyre, 2017 ). In Colombia, Rivera-Ruseria (2021) found that students’ anxiety is caused by teachers’ gestures, peer mockery, and fear of speaking. The results of her study show that previous learning experiences and beliefs about their abilities to speak a foreign language are strong determinants of learners’ anxiety.

The above-described findings suggest that secondary school students in the city of Veracruz experience positive emotions more frequently than negative ones while learning English, which is in line with a study conducted in Argentina with secondary students enrolled in a language and literature class (Martinenco et al., 2020). The participants of the foregoing study reported experiencing pride more than any of the emotions included in the AEQ instrument, with enjoyment being the second most experienced. In this study, secondary school students also reported pride to be their most frequent emotion, while enjoyment was the third most experienced. The results of both studies show that secondary school students seem to experience more positive than negative emotions in their language classes.

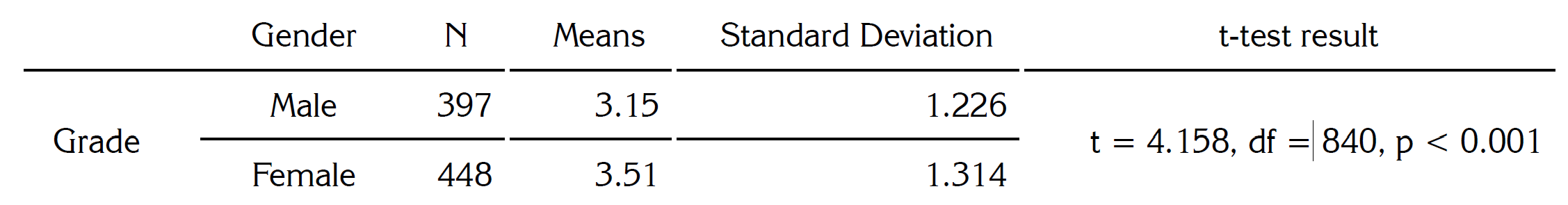

The second research question was formulated in order to examine whether there was a gender difference in the positive and negative emotions experienced by secondary school students. In general, no difference was found, with participants of the present study seeming to experience the same emotions irrespective of their gender. However, statistical differences were found for three of the emotions included in the questionnaire: pride, anxiety, and shame. Table 3 shows that female participants self-reported experiencing these emotions more than their male counterparts in their English language classes.

In Ecuador, Coutinho dos Santos et al. (2020) found that anxiety was more commonly reported by male students, whereas women reported more fear of being judged and making mistakes. An opposite result was found in this study, since women reported higher levels of anxiety and shame than men. The foregoing finding may be explained either by the fact that women have been reported to be more aware of their emotions than men (Valadez et al., 2010 ), or that men may be more reticent to show or express their emotions. Women, in turn, are more open to showing their pride when they get good grades or complete an exercise successfully (Tapia and Marsh, 2006). Moreover, girls may be more willing to show their shame and anxiety than boys at this age, as, in our culture, girls’ emotions are more openly acknowledged by their parents than those experienced by boys (Barcelata et al., 2004. Ovejas, 2020 ). Typically, at the secondary level of education, boys act more bravely and are very careful not to lose face in front of their male and, especially, female peers, covering their shame and anxiety under an indifferent façade. Furthermore, the male culture of machismo that remains influential in Mexico must also be considered, as this may be another reason why young male learners do not express their emotions.

The third research question aimed to ascertain whether there are any differences regarding the level of achievement reported by female and male students. Table 4 shows that female secondary school students self-reported higher levels of achievement than their male counterparts in their English classes.

Table 3: Differences in the emotions experienced by gender

Gender

Number

Mean

Standard Deviation

t-test results

Pride

Male

397

3.2758

.70808

t = 2.226, df = 843, p = 0.026

Female

448

3.3850

.71549

Anxiety

Male

397

1.9673

.75724

t = 2.131, df = 843, p = 0.033

Female

448

2.0826

.80885

Shame

Male

397

1.7645

.85166

t = 2.366, df = 843, p = 0.018

Female

448

1.9085

.90949

Third-grade students self-reported achieving the highest scores (80-100), while first-grade students self-reported the lowest scores (60-79), a result that may be due to the process of first year students becoming used to the secondary school environment, English classes, and the social and emotional changes they are experiencing (Barcelata et al ., 2004). For some first graders, this may be their first experience of learning a foreign language while making friends and getting to know their peers. In the case of third-grade students, they already know their teachers and their teaching styles. They are familiar with the school environment and may already have established a support network. In this study, women reported higher grades than men. This result is in line with a study conducted by Buenrostro-Guerrero et al . (2012), which found that first grade female students obtained higher grades than men, and that women scored higher in emotional intelligence. They concluded that the better the management of emotions, the greater the academic achievement.

Table 4: Differences in the level of achievement in English classes by gender

Table 5: Differences in the level of achievement in English classes by gender

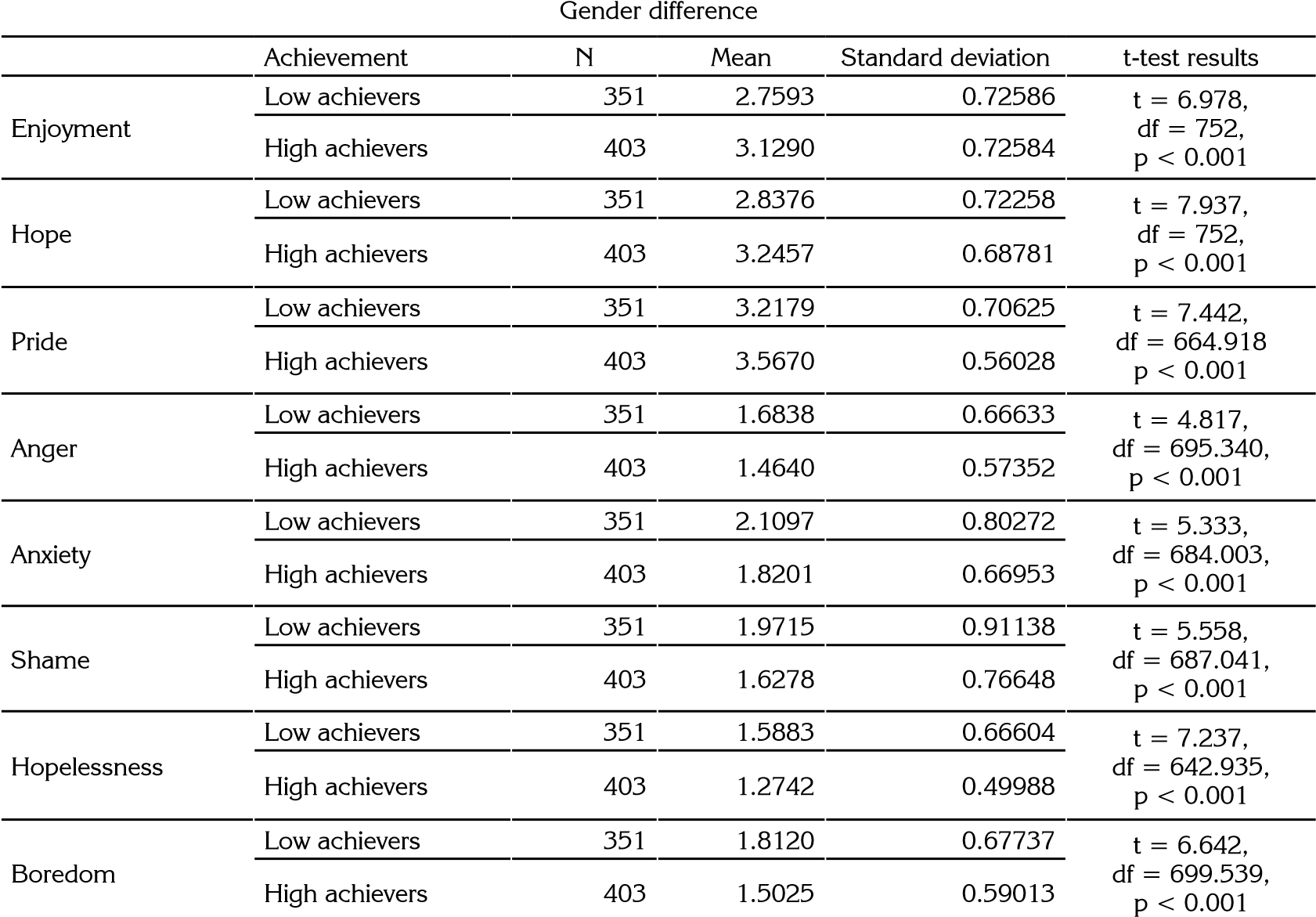

Independent t-tests were used to examine the emotions experienced by the 754 students who selfreported either higher (81-100) or lower scores (6080). The 91 students who reported grades below 60 were not included in the t-test. Table 5 shows that students who obtained higher grades experienced more pride, hope, and enjoyment, while those who reported lower grades experienced more anxiety, shame, boredom, anger, and hopelessness.

These results indicate that students who experience more positive emotions get better grades, while those experiencing more negative emotions get lower grades. As Pekrun (2017) claims, positive emotions experienced while learning can enhance engagement, interest, and curiosity, as well as increase academic performance and achievement. The results obtained by this study correlate with a quantitative study carried out with first-grade secondary students in Mexico (Buenrostro-Guerrero et al., 2012). The researchers found that women obtain higher grades than men and score higher in emotional intelligence than their male classmates. Furthermore, the results of a study conducted in the Philippines found that enjoyment and pride are good predictors of higher grades (Villavicencio and Bernardo, 2013). Our results are consistent with a study conducted on British high school students studying foreign languages, which revealed that positive emotions correlate with achievement (Dewaele et al., 2018).

Discussion

The presence and influence of emotions in foreign language classrooms has been widely reported in the literature (Csizér et al., 2021). This study examined the experience of emotions by secondary school students in Veracruz, Mexico. The findings corresponding to the first research question revealed that students reported experiencing more positive than negative emotions, with pride, hope, and enjoyment being the most reported emotions, whereas hopelessness and boredom were the least reported. These findings are consistent with research conducted in different contexts (Martinenco et al., 2020. Piniel and Albert, 2018. Buenrostro-Guerrero et al ., 2012). Furthermore, they suggest that students at secondary schools in Veracruz experience a positive language learning process, as they reported more positive than negative emotions. Positive emotions have been reported to lead students to focus more on tasks, increase self-efficacy, and boost both interest and motivation (Dewaele et al ., 2018. Pekrun, 2017 ). Thus, positive emotions should be evoked in language classrooms to assist learners in improving their social and emotional competency, with the purpose of improving their academic performance.

Regarding the differences in the emotions experienced by male and female learners, a statistically significant difference was found for three of the emotions included in the instrument. Female respondents self-reported experiencing more pride, shame, and anxiety in their Englishlanguage learning process. These results are in line with those obtained by Retana-Alvarado et al . (2018), who found that female students reported experiencing stress and fear with greater intensity than other negative emotions. However, this finding is contrary to the results obtained by a study conducted on Malay secondary school students (Abdullah et al., 2004), which found that female students experienced very low levels of negative emotion, such as frustration, anger, and anxiety. The study also reported that these female students had a higher emotional quotient (EQ) than their male counterparts, which may explain why they reported such low levels of negative emotion. Although this study did not test learners on their EQ, some were still adjusting to the secondary school environment, making friends, and experiencing new teaching styles, all of which may have affected the emotions they experienced. Another possible explanation lies in the relationship that the Malay students may have developed with their teachers, as the teacher-student relationship has been reported to influence both the type of emotions experienced by students and their level of achievement (Clem et al., 2021).

Different studies suggest that males are not open to showing their emotions, especially during their teenage years (Buenrostro-Guerrero et al., 2012. Rodríguez-Pérez, 2014 ). The fact that men are often considered stronger than women may be one reason why they do not show their emotions as openly as women. Another possible explanation is that women are more willing to share their life experiences with friends, mothers, or relatives when seeking advice or support, unlike men, especially in Latino cultures (de Prada, 1993). As found by Barcelata et al. (2004), Mexican male adolescents express not having someone to trust and are usually pressured by parents to comply with the social rules imposed on men. In this vein, Buenrostro-Guerrero et al . (2012) found that Mexican female secondary students demonstrate higher levels of emotional intelligence and seem to be better than men at feeling, expressing, and managing their emotional experiences. As concluded by Barcelata et al., “sociocultural factors influence on the expression of emotions by adolescents’ women than men” (2004, p. 72).

With regard to gender differences in foreign language achievement, female respondents in this study self-reported higher grades than their male counterparts, a surprising result, given that, although they reported more pride, shame, and anxiety, they also reported higher levels of achievement in English. This finding correlates with a study conducted in Mexico with first-grade secondary students, in which females scored higher in emotional intelligence and showed better achievement than their male counterparts (Buenrostro-Guerrero et al., 2012). As discussed above, the experience of negative emotions alongside numerous positive ones is useful for a learner’s development ( Duarte-Melgarejo, 2014 ). The highest scores were obtained by female third-graders, and the lowest ones by female firstgraders. This may be explained by the transition from elementary to secondary school, which affects first-graders both physically and emotionally (Barcelata et al., 2004. Trigoso, 2013 ), whereas third-graders may have developed a resilience to negative emotions due to their learning experiences in the previous two years. Furthermore, the fact that females in first grade may be learning English for the first time may affect their learning process and achievement levels, whereas female third graders have already developed strategies and some proficiency in the foreign language (RetanaAlvarado et al., 2018).

This study found that secondary school students in Mexico experience more pride, hope, and enjoyment in their English classes, emotions that have been reported to enhance language learning by focusing students on tasks and boosting their self-efficacy and motivation (Méndez-López and Peña-Aguilar, 2013). The female students reported experiencing higher levels of one positive and two negative emotions, as well as higher levels of achievement in their English language learning. This result is opposite to that found by the OECD (2021), which reported poorer academic performance in females than in males.

There are reports in the literature stating that experiencing some negative emotions alongside numerous positive emotions causes students to reflect and look for ways to improve their language performance in future tasks or activities (Ganotice et al ., 2016. Pekrun, 2017 ). Thus, cultural differences should be kept in mind when reporting emotions as negative per se, as they may provoke detrimental behaviors in learners in some contexts, but not in others.

Limitations

One of this study’s clear limitations is that the respondents could only refer to the eight emotions included in the instrument used. Language learners around the world have described experiencing more emotions (such as fear, anger, and despair) in educational contexts. Moreover, as the subjects of the present study (Mexican secondary school students) were experiencing physical, social, and emotional changes given their developmental stage, the results obtained should be interpreted with caution, as learning environments and circumstances can affect the emotions experienced. Different results for the same emotions have been reported by studies conducted in diverse contexts ( Teimouri, 2018 ).

Future research should examine the emotion of shame, so as to deepen our understanding of how Mexican students react to shame and the actions it triggers. Studies on the causes and effects of negative emotions may entail significant theoretical and pedagogical implications, while research focusing on the expression, recognition, and management of emotions in male learners in Mexico should also be carried out in order to explore any differences they may reveal.

Future research should address, via a mixedmethod approach, studies conducted in the Mexican context in order to provide detailed descriptions of how individual learners react to specific emotions, as well as the strategies they use to make their emotions work for them rather than against them.

Conclusion

To conclude, this study is the first attempt to provide quantitative evidence of the emotions experienced by students in public secondary schools in Veracruz, Mexico. Males and female learners reported more positive than negative emotions in their English classes. As revealed by various studies, positive emotions lead learners to develop learning strategies (Hamideh et al., 2020) and improve their emotional competency and motivation, actions that can improve their academic performance (Dewaele et al ., 2018).

A particularly interesting finding is that women reported more shame and anxiety than men. Thus, teachers should beware of the effect of mocking or judging when female students participate in class, as this seems to be a factor arousing negative emotions in them. Although females reported more shame and anxiety, they also obtained better grades. It seems that those negative emotions acted as a learning force that encouraged them to improve their English language proficiency as not to experience said emotions frequently. Thus, the role of shame should be investigated in our context in order to deepen our understanding of this emotion. A better understanding of the actions triggered by positive and negative emotions can help teachers to implement strategies that help learners manage and regulate their emotions.

References

Appendix 1

This questionnaire was designed to find out what emotions you have experienced while in English classes in secondary school. Please note that this is NOT an evaluation of how good a student you are, but rather a way to learn more about the role played by emotions in your learning of English.

SECTION I. In this section, the questions refer to the emotions or feelings that you have experienced when learning English. Try to remember some situations that you have experienced in your English classes. Read carefully and select the answer that most closely matches your opinion.

1 = Never 2 = Hardly ever 3=Usually 4= Always

____ I enjoy being in my English class.

____ I feel confident that I will be able to master the material in class.

____ I think I can be proud of my accomplishments in studying English.

____ I get annoyed about having to study English.

____ I get tense and nervous while studying.

____ When somebody notices how little I understand, I feel ashamed.

____ I have lost all hope in understanding this class.

____ I think about what else I might be doing rather than sitting in this boring class.

____ I am motivated to go to this class because it is exciting.

____ Being confident that I will understand the material motivates me.

____ When I do well in class, my heart throbs with pride.

____ When I think of the time I waste in class, I get aggravated.

____ Even before class, I worry whether I will be able to understand the material.

____ I feel ashamed when I realize that I lack ability.

____ I am resigned to the fact that I do not have the capacity to master this material.

____ Studying during my English course bores me.

Metrics

License

Copyright (c) 2022 Mariza Méndez López

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.