DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.11987Published:

2018-02-16Issue:

Vol 20, No 1 (2018) January-JuneSection:

Reflections on PraxisPromoting meaningful encounters as a way to enhance intercultural competences

Promoviendo encuentros significativos como una forma de mejorar las competencias interculturales

Keywords:

antecedentes culturales, competencias interculturales, competencias, foros virtuales (es).Keywords:

Intercultural competences, skills, cultural backgrounds, virtual forums (en).Downloads

References

Barnett, R. (1997), Higher Education: A Critical Business. Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press.

Barreto, C. (2011). Development of Intercultural Competences in Virtual Learning Environments. “Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte”. 34, 194- 219. Retrieved February 8th, 2016 from http://revistavirtual.ucn.edu.co/

Bennett, M. J. (1986). A developmental approach to training for intercultural sensitivity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10, 179-196.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communication competence. New York: Multilingual Matters

Byram, M., Gribkova, B., & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching: a practical introduction for teachers [Electronic Version]. Retrieved February 8th, 2016 from http://lrc.cornell.edu/rs/roms/507sp/ExtraReadings/Section0/Section0/uploads/File1235272745204/InterculturalDimensionByram.pdf

Deardorff, D.K. (2006). The identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization at institutions of higher education in the United States. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10(3), 241-266.

Deardorff, D. K.,(2014). Some Thoughts on Assessing Intercultural Competence [Electronic Version]. Retrieved February 8th, 2016 from https://illinois.edu/blog/view/915/113048

Deardorff, D. K.,(2016). How to Assess Intercultural Competence. In

Zhu, H. (Ed.), Research Methods in Intercultural Communication: A Practical Guide (pp. 120-135). West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Dervin, F. (2015) On the dangers of intercultural competence. 11. Program from Intercultural Competence in Communication and Education (ICCEd) 2015. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Universiti Putra Malaysia.

Dervin, F. (2016) How Current Understandings of Language and Culture (Should) Inform L2 Pedagogy. 10-11. Program from Fifth International Conference on the Development and Assessment of Intercultural Competence 2016. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona.

Fantini, A. E. (1995). Language, culture, and world view: Exploring the nexus. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 19, 143-153.

Fantini, A. E. (2009), Assessing Intercultural Competence: Issues and Tools. In Deardorff, D. K. (ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage, 456- 476.

Griffith, D. A., & Harvey, M. G. (2000). An intercultural communication model for use in global interorganizational networks. Journal of International Marketing, 9 (3), 87-103.

Holmes, P. and O’Neill, G. (2012). Developing and evaluating intercultural competence: ethnographies of intercultural encounters. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 36(5), pp. 707-718.

House, J. (2007). What is an intercultural speaker? In Soler, E. A. & Safont Jorda, M. P. (Eds.), Intercultural language learning and language use (7-21). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. Retrieved May 15th, 2016 from https://eslebooklibrary.files.wordpress.com/2009/07/interculturallanguageuseandlearn.pdf

Howard Hamilton, M. F., Richardson, B. J., & Shuford, B. (1998). Promoting multicultural education: A holistic approach. College Student Affairs Journal, 18, 5-17.

Muyuy Jacanamejoy, G. (2014). Interculturalizar la educación superior para interculturalizar la sociedad. In Hacia la Interculturalización de la Educación Superior (5). Retrieved February 8th, 2016 from http://www.colombiaintercultural.gov.co/Documents/Cartilla-Seminario-Educacion-Superior.pdf

Neuner, G. (2012). The dimensions of intercultural education Gerhard. Intercultural competence for all: Preparation for living in a heterogeneous world. Retrieved May 15th, 2016 from http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/education/pestalozzi/Source/Documentation/Pestalozzi2_EN.pdf

Reitenauer, V. L., Cress, C. M. & Bennett, J. (2005). Creating cultural connections: Navigating difference, investigating power, unpacking privilege. In C. M. Cress, P. J. Collier, & V. L. Reitenauer (Eds.), Learning through serving: A student guidebook for service-learning across the disciplines. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Spitzberg, B. H., & Chagnon, G. (2009). Conceptualizing intercultural communication competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 2-52). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Spitzberg, B. H. (2012). Axioms for a theory of intercultural communication competence. Annual Review of English Learning and Teaching, 14, 69-81.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Promoting Meaningful Encounters as a Way to Enhance Intercultural Competences

Promoviendo encuentros significativos como una forma

de mejorar las competencias interculturales

Laura Carreño Bolivar1

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Carreño, L. (2018). Promoting Meaningful Encounters as a Way to Enhance Intercultural Competences. Colomb. appl. linguist. j., 20(1), pp. 120-135.

Received: 10-May-2017 / Accepted: 09-Jan.-2018

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.11987

Abstract

This article presents a pedagogical experience in which a course aiming at the development of intercultural competences was taught to university-level students in a Colombian higher education institution. Topics such as minority groups, national identity, and racism were included in the course syllabus in order to raise students’ awareness regarding the importance of interculturality. Data were collected from students’ individual and group posts to the virtual forums proposed every week. In addition, survey responses contributed to determining the influence of the course on the development of intercultural competences. Findings suggest that interacting with individuals coming from various cultural backgrounds increases one’s awareness and appreciation of difference as a valuable and particular asset of human nature.

Keywords: cultural backgrounds, intercultural competences, skills, virtual forums

Resumen

El presente artículo tiene como objetivo compartir la experiencia obtenida al impartir un curso que apuntaba al desarrollo de Competencias Interculturales en estudiantes universitarios de una institución Colombiana de educación superior. Temas como las minorías, la identidad nacional y el racismo fueron incluidos en el programa del curso con el fin de sensibilizar a los estudiantes sobre la importancia de la interculturalidad. Con el fin de retratar las percepciones de los estudiantes acerca del curso y su influencia en el desarrollo de las competencias interculturales; se incluyó el análisis de los mensajes individuales y grupales de los estudiantes a los foros virtuales que se proponían semana a semana, además de sus respuestas a una encuesta individual. Los hallazgos sugieren que la interacción con personas procedentes de diversos contextos culturales aumenta la conciencia y la apreciación de la diferencia como un rasgo valioso y particular de la naturaleza humana.

Palabras clave: antecedentes culturales, competencias interculturales, competencias, foros virtuales

Introduction

Intercultural competences (IC) is a trendy term that reunites all those ‘abilities’ that people should possess in order to interact appropriately and effectively with people from different cultural backgrounds (Bennet, 1986). However, thinking about the relevance of intercultural competences in a person’s life is what really matters when planning and teaching an interculturally-focused course.

Although multi- and intercultural education has been a topic of interest for several cultural and educational organizations in Colombia since the late 1990s, most of the research conducted focuses on the need for ethnic minorities and languages to be integrated into the existing educational system of our country which fails to acknowledge both their native languages and religious beliefs. It is widely accepted that intercultural education should focus on the needs of indigenous and ethnic minorities; nevertheless, as stated by Clavijo-Olarte and Gonzalez (2016), “although Indigenous groups consider education as a relevant element to empower their social and cultural conditions, some curricular and educational contexts lack knowledge about Indigenous people’s ways of learning causing a mismatch between the community interests and schools” (p. 433).

Our country is still lacking development in terms of the conditions needed for the academic success of Indigenous communities. The most important aspect is that there should be a shift in the view of education that has shaped the development of educational policy. Due to the difficult conditions that surround the integration of Indigenous communities into the ‘dominant’ society, institutions perceive their roots and identity as obstacles for them to cope with the needs of ‘standard’ education. Guerrero (as cited in Clavijo-Olarte & Gonzalez 2016) states that “Colombia has a variety of languages that should be seen as resources and not as problems” (p. 432).

Although some of the literature addresses governmental attempts to include Indigenous communities into the “dominant” educational system; most of it addresses topics such as geography, history, and sociology. In a review of the literature, Castro Suárez (2009) asserts that there is limited work in terms of the educational situation of indigenous and afro communities, multiculturality, cultural diversity, and etnoeducación, (a term proposed by the Colombian Ministry of Education as a way to offer education to indigenous communities that addresses their specific needs; Arbeláez Jiménez & Velez Posada, 2008).

Up to now, the Colombian Ministry of National Education (MEN) has developed several initiatives regarding etnoeducación. According to the principles promulgated by the MEN, in documents such as “Politicas Educativas sobre la Interculturalidad” (Velez-White, 1994); etnoeducación should indeed respect minorities’ beliefs regarding cultural identity, religion, and language. Colombian ethnic minorities should at least be guaranteed, officially, that their children have access to primary education in order to acquire reading and writing abilities both in their native language and in Spanish; however, these basic rights have been openly neglected and “generally undervalued and associated with an invisible form of bilingualism” (De Mejia, 2006, as cited in Clavijo-Olarte & Gonzalez 2016, p. 435). In recent years, the MEN has studied many of these issues in relation to the situation of the minority languages as promulgated by “Proyecto de Fortalecimiento de la Educación Media y Tránsito a la Educación Terciaria 2014-2021 Marco de Planificación para Grupos Étnicos (Mpge; MEN, 2014),” but little attention has been given to issues such as teacher-training, learning and teaching materials, and social equity policies.

Government efforts have principally focused on the establishment of policies that acknowledge difference; such policies not only invite people to tolerate each other but to value the abundance of cultural heritage existing within a single country. It is highly important that government policies recognize that all members of the Colombian society, regardless of beliefs, race, or ethnic origin, play a fundamental role in the construction of national identity. According to Muyuy Jacanamejoy (2014), the inclusion of intercultural competences in higher education is key to the establishment of a society in which persons respect and are aware of their rights and duties as individuals and as members of a community. Additionally, Muyuy Jacanamejoy

(2014) highlights the significance of having higher education institutions embrace IC as a group of competences that needs to be included in the academic curricula of all majors. What is more, efforts should be made to create institutions that, despite being mainly focused on the development of IC, are still capable and willing to interact with other fields of knowledge to satisfy both indigenous communities and Colombian citizens in general in order to reaffirm national identity.

Regarding this issue, Barreto (2011) argues that although some institutions have made efforts to initiate the inclusion of IC into their programs, the development of IC is not contained within the group of competences that must be learned by students. What is more, educators do not count on a formal curriculum that addresses IC explicitly either in virtual or in online programs.

As higher education has been the context of my 10 years of experience as a language educator, I have had the chance to teach not only language courses but also diploma courses whose focus (as stated in the syllabi) is to develop IC in students. These courses have been developed over several years, and, for over three years, I have been in charge of adapting previous programs and creating new ones in order to offer the academic community (national and international students from over 20 majors) alternatives to practice their English skills and to learn about other cultures.

In spite of these efforts, it was evidenced that, differently from international students, national students were not aware enough of the relevance that IC have for both their professional and personal development. As stated by Cruz Arcila (2007), “we usually tend to perceive our own culture as the appropriate way of looking at and doing things, and of perceiving reality” (p. 146). This was, sadly, the most common attitude assumed by the Colombian participants of the course before being exposed to activities planned in order raise their awareness and appreciation of difference.

The fact that international students are more aware of the relevance of IC was continuously evidenced throughout the implementation of the mentioned diploma courses. Activities such as debates, virtual forum discussions, and in-class presentations (among other activities) substantially demonstrated how those international students counted on more tools as to perform successfully in social and cultural backgrounds which were considerably different from their own.

The issue described above triggered my interest in researching the acquisition and development of intercultural competences in Colombia, particularly at the level of higher education. It has been my interest to find out whether and how the implementation of these diploma courses contributes to the development of IC on the one hand, and, on the other, how these courses maintain, and hopefully increase such awareness in international students. However, creating an environment in which national and international students’ intercultural abilities can actually develop has not been an easy task. Cruz Arcila (2007) also emphasizes the fact that:

Currently, we are facing many instances of cultural contact that may lead to situations of conflict if we are not prepared to deal with this. Nowadays, language learners need to be provided, not only with linguistic tools, but also with cultural knowledge for them to be prepared for intercultural communication. (p. 148)

When conflict takes place, classroom environment can become harsh and result in

students refraining from expressing their opinions and insights. It is of utmost importance to train students in the development of competencies that allow them to understand, comprehend, and respect others. However, it is difficult to determine how respectful our students are regarding a specific aspect, but it is possible to assure their exposure to controversial topics that motivate students to think critically and reflect upon unknown matters.

What are Intercultural Competences?

Several studies on the definition of the term intercultural competences have been conducted over the years, given its relevance especially in higher education where “students from different contexts come together to live and learn” (Holmes & O’Neill,

2012, p. 707). However, taking a look at various studies, it is clear that discrepancies abound among the authors who, according to their perspectives, value some characteristics more than others.

Reitenauer et al. (2005) defined intercultural competences as “the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in a variety of cultural contexts” (p. 68). Taking a look at the words “effectively and appropriately,” one could consider that what is appropriate and effective in a specific context may not have the same appreciation in other settings. In a project conducted by Spitzberg and Chagnon (2009), five basic types of intercultural communicative competences (ICC) were identified including “compositional, co-orientational, developmental, adaptational, and casual” (p. 425).

Authors such as Fantini (1995) and Byram (1997) have developed models that correspond to a compositional ICC model which is related to the attitudes, knowledge, and skills that ICC comprises at an individual level (Howard-Hamilton, Richardson, & Shuford, 1998). The co-orientational model refers to those symbolic and pragmatic moments of interaction that lead the parts involved to find commonalities; and, developmental ICC models focus on the importance of processes in the acquisition of intercultural competences, Bennet (1986) proposes a model in which acceptance of the new culture precedes the adaptation and integration phases of the ICC development process. Unlike compositional models, adaptational ICC models focus on a “dyadic or group perspective” (Spitzberg, 2012, p. 426) in which one communicator adjusts their behavior to that of the other’s culture. Finally, causal models are those in which certain conditions are pre-established in order to predict the outcome of an intercultural system or relationship (Griffith & Harvey, 2000).

Additional to the ICC models identified by Spitzberg and Chagnon (2009), Spitzberg proposes another ICC model called “relational”

which comprises several elements included in the adaptational, developmental, and causal models. The relational model focuses on the outcomes that result from intercultural communication encounters. Spitzberg (2012) asserts that “the model outcomes include intercultural effectiveness, communication effectiveness, relational validation, intimacy, relational satisfaction, relational commitment, relational stability and uncertainty reduction” (p. 427).

The model proposed by Spitzberg appears then as the most suitable model for the purposes of this experience given that it considers not only a set of skills that an interculturally knowledgeable communicator must possess in order to be successful but it also focuses on specific outcomes that a communicator obtains once an intercultural communicative event has occurred. Considering that communicative and interactive events are those which actually measure one’s ability to efficiently communicate with people who come from different contexts and backgrounds, the relational model tackles issues that other models had overlooked. Here, adaptability becomes a critical aspect in order to navigate a mighty ocean of cultures. In this sense, Dervin (2015) asserts that intercultural competences are seen as:

The values, attitudes, skills, knowledge and critical understanding that enable us to participate effectively in today’s diverse democracies, these competences are said to include the following (canonical) aspects: responsibility, tolerance, conflict resolution, listening skills, linguistic and communication skills, critical thinking, empathy and openness. The ultimate goal is to propose “a universal and objective system to define and measure the democratic competences required. (p. 11)

From a more critical perspective, Dervin (2016) talks about the “commercial” shift that IC have acquired over the years. He asserts that “intercultural competences can easily be used as an intellectual simplifier or as a simplistic and deterministic slogan idea, which contributes to pinning down and labeling people” (p. 10). The downside to IC that the proposed methods have ignored is that instead of acknowledging differences, people are demanding others to think, behave, and act similarly (if not equally) to them (those who belong to the culturally dominant context).

Secondly, Dervin (2016) considers that one of the major issues within intercultural competence nowadays is the overreliance on the term “culture” which has been a subject of study for several years but which has also been recently removed from several research grounds. In this way, he suggests that:

The over-reliance on culture to explain intercultural encounters leads us to concentrate on difference only and to compare and judge willy-nilly the self and the other, often leading to ethnocentrism, (explicit and/or implicit) moralistic judgments and social injustice. This orthodoxy is intolerable in our accelerated globalized times. (p. 10)

As argued by Dervin, it is clear that modern times do not go hand-in-hand with studies that exclusively focus on culture and the differences that exist among individuals whose backgrounds differ. It is of utmost importance to find commonality instead, which will lead us to a search for understanding, awareness, and willingness to accept and adapt ourselves to people and situations that do not share similar characteristics with our own society. The word tolerance would have to be replaced given that tolerating others brings with it a sense of self-sacrifice on behalf of the individual who tolerates the other. It should not be about who sacrifices and endures others more in order to have a truly intercultural encounter. It should be about two communicators who appreciate, acknowledge and value difference as a source of wisdom for life.

Nevertheless, these new definitions of IC have been opposed by researchers and educators all over the world who have adopted and adapted older models and who have had successful experiences with those. In my view, the discussion should not be about which model to choose but about the evolution that IC have had now that we live in a much more globalized society in which people from all over the globe face intercultural encounters on an almost daily basis. It is not only a demand for educators but for governments and public institutions to raise awareness on the importance of IC in order to avoid judgment, racism, and social injustice, among others.

Is it possible to Assess Intercultural Competences?

The question as to whether cultural competence should be assessed or not has been a subject of discussion for several years in the field, and several models for IC assessment have been proposed. Yet, most of those models have been challenged due to the subjectivity involved when trying to determine the kinds of tests that people should be submitted to in order to determine how interculturally competent they are. Byram, Gribkova, and Starkey assert that assessing knowledge is thus only a small part of what is involved. What we need is to assess ability to make the strange familiar and the familiar strange (savoir etre), to step outside their taken for granted perspectives, and to act on the basis of new perspectives (savoir s’engager).

The authors refer to how difficult it would be to assess IC as a humanistic concept that cannot and should not be quantified due to the fact that measuring one’s ability to tolerate and value differences is only possible by using purely qualitative methods. One way proposed by the authors was a thorough description of a person’s competences by means of a portfolio:

The portfolio introduces the notion of selfassessment, which is considered significant both as a means of recording what has been experienced and learnt and as a means of making learners become more conscious of their learning and of the abilities, they already have. (Byram et al., 2002, p. 24)

Basically, the model proposed by Byram et al. (2002) gives learners a chance to evaluate the intercultural experiences they live. The authors propose portfolios in which students keep record of and reflect upon aspects such as feelings, knowledge, and actions that occurred during the course of the intercultural experience. In this way, “the role of assessment is therefore to encourage learners’ awareness of their own abilities in intercultural competence, and to help them realize that these abilities are acquired in many different circumstances inside and outside the classroom” (p. 26).

Fantini (2009) asserts that intercultural competences comprise “complex abilities that are required to perform effectively and appropriately when interacting with others who are linguistically and culturally different from oneself” (p. 468).

124

However, as argued by many other authors, it would be necessary to list millions of skills in order to create some sort of bank of intercultural competences that can be used by people all over the globe according to a specific context, culture, or situation.

In recent years, many other models have been proposed. Deardorff (2014) stated that for IC to be evaluated, “it should be broken down into more discrete, measurable learning objectives representing specific knowledge, attitudes or area skills” (Assessment of Intercultural Competence— Myths, Themes and Implications section, para.4). Analyzing these modern models for the assessment of intercultural competence, it is evident that scholars have realized the need to focus our attention on the development of a model that assesses more specific features evidencing how knowledgeable people become after being exposed to several intercultural encounters and given a chance to analyze and reflect upon their performance. However, it seems that most of the assessment tools that have been created over the years mainly focus on how people self-evaluate their skills and the perceptions they have about themselves. In her most recent publication, Deardorff (2016) states that:

What is often missing in the assessment of intercultural competence (at least in education and the humanities) is the other half of the picture—the appropriateness of communication and behavior, which, according to research studies, can only be measured through other’s perspectives, beyond self-report. This can be done through observation of behavior in real life situations or through surveys completed by other persons engaged in the interactions. (p. 122)

The perspective presented by Deardorff is both enriching and innovative and goes beyond what has been established as the assessment of Intercultural Competences for several years. Previous studies focused exclusively on having students reflect upon their performance, abilities and skills regarding intercultural encounters; however; self-evaluation is not always accurate as one’s view can be biased by numerous factors. It is important to count on other people’s perspectives in order to get an idea on how ‘efficient’ the interactions were.

Asking other people can provide more objective insights that progressively shape and modify attitudes, feelings and behaviors to become more proficient intercultural communicators.

Methodology and Context

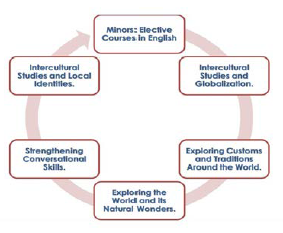

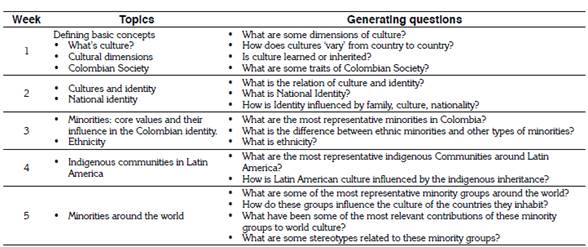

The experience shared in the present article is about the implementation of several lessons in which students from different cultural backgrounds had the opportunity to analyze, provide opinions, and discuss varied topics that dealt with culturally-related issues present in today’s society. The context of this study is a higher education institution in Colombia, South America. For this institution, and more specifically for the Department of Languages and Cultures (DLC), it is of utmost importance to provide students with a wide range of skills that contribute to their future success. In response, the DLC created a group of courses (see Figure 1) which are not focused on teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFL); on the contrary, the courses focus on the development of intercultural competences by providing students with input regarding cultural aspects and manifestations in several cultures.

Figure 1. Minor courses available.

For this particular implementation, the course titled “Intercultural Studies and Local Identities” was selected due to the fact that it focuses on those aspects of national culture and identity that any human being, regardless of nationalities or backgrounds, can talk about and analyze in depth. It was considered that for genuine interaction and critical thinking to take place, it would be necessary to plan lessons in which everyone felt touched and moved.

The mechanics of the course were quite simple. Students attended a total of 64 face-to-face hours divided in two-hour blocks twice a week. In addition to the four weekly face-to-face hours, they were also asked to devote an extra hour to work on virtual activities. The face-to-face hours mainly included studying, analyzing, and understanding different (and as neutral as possible) sources of information regarding the topics selected for each week.

During these sessions, students were presented with a series of resources that dealt with the topic of interest. It was my objective to include topics that could actually generate discussion and that motivated students to disclose their insights regarding different matters which would, in turn, result in the increase of their intercultural awareness which as stated by Baker (2012) is:

A conscious understanding of the role

culturally based forms, practices, and frames

of understanding can have in intercultural communication, and an ability to put these conceptions into practice in a flexible and context specific manner in real time communication. (p. 5)

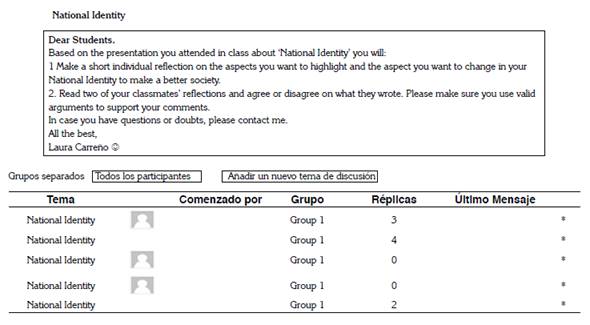

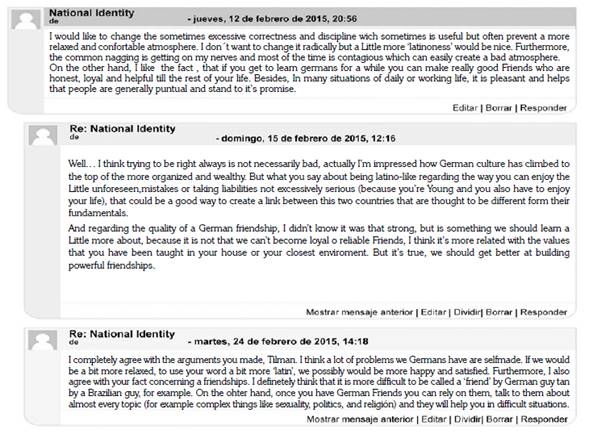

Intercultural awareness in this particular experience plays a major role since the main intention of the implementation was to expose learners to different views of the world. A series of videos, articles, and guest speakers were some of the resources that made part of the pedagogical implementation of the course. Additionally, during the virtual session, students were asked to analyze different situations and cases related to the weekly target topics, and to engage in discussions via asynchronous forums. Figure 2 illustrates how the virtual sessions were structured. I provided instruction regarding the activities in which students had to engage and specified the steps they had to follow.

For this particular activity, students were asked to reflect upon the topic discussed during the face-to-face sessions and write a short post about it. Then, they were asked to read at least two of their classmates’ posts in order to encourage discussion. Including

National Identity Dear Students,

Based on the presentation you attended in class about ‘National Identity’ you will:

1 Make a short individual reflection on the aspects you want to highlight and the aspect you want to change in your National Identity to make a better society.

2. Read two of your classmates’ reflections and agree or disagree on what they wrote. Please make sure you use valid arguments to support your comments.

In case you have questions or doubts, please contact me.

All the best,

Laura Carreño ©

Grupos separados | Todos los participantes | | Añadir un nuevo tema de discusión

|

Tema Comenzado por |

Grupo |

Réplicas |

Último Mensaje | |

|

National Identity |

Group 1 |

3 |

* | |

|

National Identity |

Group 1 |

4 |

* | |

|

National Identity |

Group 1 |

0 |

* | |

|

National Identity |

Group 1 |

0 |

* | |

|

National Identity |

Group 1 |

2 |

* |

Figure 2. Virtual session structure.

126

mutual reading into the instructions was an effective strategy to motivate students to provide opinions and interact with others. All the contributions made by students during the virtual sessions were used in order to ‘assess’ how interculturally competent students had become over time and with the help of the implementation. Other components such as an oral test and a class presentation were also included in order to give students more chances to show how their intercultural competences had improved and how aware they had become of the importance of differences in the construction of an open-minded society that gradually accepts others.

Participants

During the first semester of year 2015, the course “Intercultural Studies and Local Identities” (ISLI) was presented as one of the options for the academic community interested in having a different option to practice their English language skills and learn about other cultures. I had previously taught the course but in that specific semester, when I entered the classroom, I realized that out of the six students who were registered, four of them were foreign students who for different reasons had come to Colombia to either start or conclude their majors.

Six university-level students—three from

Germany, two from Colombia, and one from Haiti— joined the course. This was quite a challenge given that the course had never been taught to such a diverse audience. Initially, the course had been designed for a more “local” audience, meaning that the students who had enrolled in the course in previous semesters were mostly Colombian: a total of only six foreign students had been enrolled over the previous five years. In contrast, during this specific semester, the challenge of having several international students (four out of six) taking a course originally designed for national students was faced. Therefore, it was decided that the course needed a twist that made it a more appealing experience for the participants.

During the first session, discussion took place easily and all students participated in the proposed activities. In fact, I noticed that this group had very special characteristics that could make the learning experience a lot more enriching for the students and for my teaching practices. To be more precise, the characteristics I identified were: variety of nationalities, diverse social and cultural backgrounds (not only because of their nationalities, but also because of their life experiences), eagerness to learn about others and appreciation of differences, among others. It may seem as though it would be difficult to identify all of those characteristics in just one week; however, through a series of activities inquiring as to how much they knew about other cultures (e.g., class debates on a series of generating statements, written and spoken reflections, class discussions based on videos or reading excerpts, etc.) and how interested they were in getting to know other countries, their societies, and identities, it was evidenced that this would be a remarkable experience.

Having a more international audience was then considered to be an opportunity to focus on actually teaching intercultural competences by taking advantage of the life experiences that students from other nationalities, who had travelled around the world, could share with those who had not had such chances. It was now necessary to create an intercultural environment in which participants had the opportunity to acquire, increase, and develop the necessary competences to become successful intercultural speakers (House, 2007).

Findings

National and International Students Engaged in “Meaningful Intercultural Encounters”

As stated previously, the focus of this course in previous semesters was a matter of concern at the beginning of semester (2015-1) given the type of population that had previously taken the “Intercultural Studies and Local Identities” course. Based on the initial activities (e.g., ice-breaking, discussion, short writing exercise), I considered that the topics had to be focused differently in order to motivate students to share their insights in ways in which they could all learn new concepts and thus benefit from the course, especially from the intercultural aspect of it.

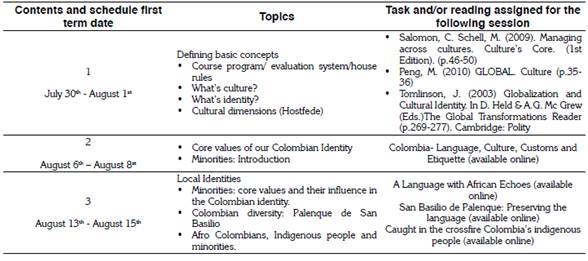

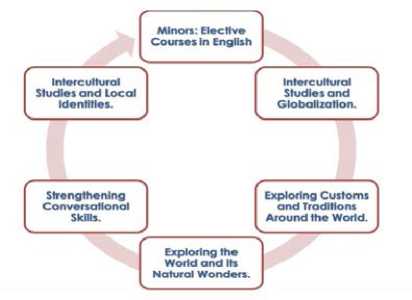

As explained in the methodology section, the course had two main components: the face-to-face sessions and the asynchronous forums. The main objective when planning was to create spaces for students not only to practice their English language skills, but also to exercise criticality (Barnett, 1997). Taking a look at the previous program (see Figure 3), I could notice that it was “too local” which could potentially make international students refrain from participating in discussion given their lack of knowledge regarding our culture.

Therefore, it was necessary to find the ‘magical shift’ that made everyone feel involved, which was not as difficult as I had thought. In the re-structured program (see Figure 4) the language used for the

|

Contents and schedule first term date |

Topics |

Task and/or reading assigned for the following session | |

|

1 July 30th - August 1st |

Defining basic concepts • Course program/ evaluation system/house rules • What’s culture? • What’s identity? • Cultural dimensions (Hostfede) |

• Salomon, C. Schell, M. (2009). Managing across cultures. Culture’s Core. (1st Edition). (p.46-50) • Peng, M. (2010) GLOBAL. Culture (p.3536) • Tomlinson, J. (2003) Globalization and Cultural Identity. In D. Held & A.G. Mc Grew (Eds.)The Global Transformations Reader (p.269-277). Cambridge: Polity | |

|

2 August 6th - August 8st |

• • |

Core values of our Colombian Identity Minorities: Introduction |

Colombia- Language, Culture, Customs and Etiquette (available online) |

|

3 August 13th - August 15th |

Local Identities • Minorities: core values and their influence in the Colombian identity. • Colombian diversity: Palenque de San Basilio • Afro Colombians, Indigenous people and minorities. |

A Language with African Echoes (available online) San Basilio de Palenque: Preserving the language (available online) Caught in the crossfire Colombia’s indigenous people (available online) | |

|

Week |

Topics |

Generating questions | |

|

1 |

Defining basic concepts • • What’s culture? • • Cultural dimensions • • Colombian Society • |

What are some dimensions of culture? How does cultures ‘vary’ from country to country? Is culture learned or inherited? What are some traits of Colombian Society? | |

|

2 |

• • |

• Cultures and identity • National identity • |

What is the relation of culture and identity? What is National Identity? How is Identity influenced by family, culture, nationality? |

|

3 |

• • |

Minorities: core values and their • influence in the Colombian identity. • Ethnicity • |

What are the most representative minorities in Colombia? What is the difference between ethnic minorities and other types of minorities? What is ethnicity? |

|

4 |

• |

• Indigenous communities in Latin America • |

What are the most representative indigenous Communities around Latin America? How is Latin American culture influenced by the indigenous inheritance? |

|

5 |

• |

• • Minorities around the world • |

What are some of the most representative minority groups around the world? How do these groups influence the culture of the countries they inhabit? What have been some of the most relevant contributions of these minority |

groups to world culture?

• What are some stereotypes related to these minority groups?

Figure 4. Re-structured course program

128

presentation of the topics was gradually modified. In that way, the frequency in usage of the word ‘Colombian’ considerably decreased and was replaced by the word ‘national’ in order to open the space for nationals from other countries to share their knowledge and insights with the class. Furthermore, a series of generating questions was posed in order to guide the inquiries and discussions to be carried out each week.

Through this shift, I intended to create a more welcoming, involving, and comfortable space for students, regardless of their nationality or background. In addition, efforts were made in order to include more topics that could let us find out more about other cultures. As stated by Barletta (2009):

Not only do teachers now have to teach culture facts, skills to interact, and positive attitudes, but they also have to develop commitment to the education of citizens that are reflective, critical, sensitive and committed to issues of human suffering and dignity both at local and global levels. (p. 147)

Sharing about their cultures and their social contexts allowed students to speak their minds regarding several concepts and aspects of society. This was, in my opinion, one of the most enriching experiences of the implementation given that sharing about taboo topics (e.g., minorities, education and health issues, racism, gender issues, etc.) required that students carefully plan their interventions taking into account the cultural

Re: National Identity

de

National Identity . ... . , . ..

de - jueves, 12 de febrero de 2015, 20:56

I would like to change the sometimes excessive correctness and discipline wich sometimes is useful but often prevent a more relaxed and confortable atmosphere. I don't want to change it radically but a Little more ‘latinoness’ would be nice. Furthermore, the common nagging is getting on my nerves and most of the time is contagious which can easily create a bad atmosphere. On the other hand, I like the fact , that if you get to learn germans for a while you can make really good Friends who are honest, loyal and helpful till the rest of your life. Besides, In many situations of daily or working life, it is pleasant and helps that people are generally puntual and stand to it’s promise.

Editar | Borrar | Responder

Re: National Identity

de - domingo, 15 de febrero de 2015, 12:16

Well... I think trying to be right always is not necessarily bad, actually I’m impressed how German culture has climbed to the top of the more organized and wealthy. But what you say about being latino-like regarding the way you can enjoy the Little unforeseen,mistakes or taking liabilities not excessively serious (because you’re Young and you also have to enjoy your life), that could be a good way to create a link between this two countries that are thought to be different form their fundamentals.

And regarding the quality of a German friendship, I didn’t know it was that strong, but is something we should learn a Little more about, because it is not that we can’t become loyal o reliable Friends, I think it’s more related with the values that you have been taught in your house or your closest enviroment. But it’s true, we should get better at building powerful friendships.

Mostrar mensaje anterior | Editar | Dividir| Borrar | Responder

- martes, 24 de febrero de 2015, 14:18

I completely agree with the arguments you made, Tilman. I think a lot of problems we Germans have are selfmade. If we would be a bit more relaxed, to use your word a bit more ‘latin’, we possibly would be more happy and satisfied. Furthermore, I also agree with your fact concerning a friendships. I definetely think that it is more difficult to be called a ‘friend’ by German guy tan by a Brazilian guy, for example. On the ohter hand, once you have German Friends you can rely on them, talk to them about almost every topic (for example complex things like sexuality, politics, and religión) and they will help you in difficult situations.

Mostrar mensaje anterior | Editar | Dividir| Borrar | Responder

Figure 5. Students’ sample post.

differences and social distinctions present in the classroom. It was decided to include such topics in order to encourage discussion that contributed to students’ awareness regarding difference and to a more positivist perception of it.

Valuing one’s culture is crucial when constructing a well-founded identity; however, it is also important to assume a critical perspective regarding one’s own culture, values, and traditions. When trying to foster intercultural competences among students, it is of high relevance to encourage learners to think of others and consider that because a specific group of people do certain things in a certain way, that they are necessarily right and their actions are correct. In a specific post made by a couple of students (see Figure 5), it was possible to see how they critically analyzed typical aspects of their own cultures (Colombian and German) and addressed aspects that, to their view, are both positive and negative. What was most interesting was that when one of the students highlighted something negative regarding their culture, this was appreciated as a positive aspect to those who did not belong to their same background.

In this particular post, differences were appreciated as valuable characteristics of a culture whose members might consider too flexible and relaxed. Contrary to what most people may think, the German students participating in this study mentioned how beneficial it would be for their culture if they adopted a ‘Latin’ attitude to see problems in life; they justify this by saying that their excessive discipline creates more problems than solutions, which makes them unhappy in a number of ways.

One of the most valuable insights gained from the experience was that citizens from a developed country who have probably had better life quality and more opportunities in all senses, considered that living in a developing country has made them realize how simple differences have an important role in the way people react to everyday situations. In this case, the participant asserted that his compatriots are constantly complaining and assuming negative attitudes in different situations, which can be contagious; therefore, he appreciates how Latinos are more cheerful and assume positive attitudes when facing difficult situations. This also contributed to having local students reflect upon how wealthy their culture is, and how they are valued by others.

Our national identity has been undermined throughout history due to several issues dealing with historical, political, and social events that have created a collective sense of national shame. Authors like Fowler and Lambert (2006) argue that:

Given that national identity can either powerfully reinforce or deeply undermine the state, the inability of the Colombian state to create a legitimate national identity has left it lacking one of its key components. Without a unifying national vision the state is condemned to weakness and violent conflict. (p. 94)

Considering this, for the purposes of this experience education becomes a crucial tool to help people become more proud than ashamed of their country and their national identity. Being proud of one’s own culture opens the door to a more open-minded society that appreciates difference as an irreplaceable human asset.

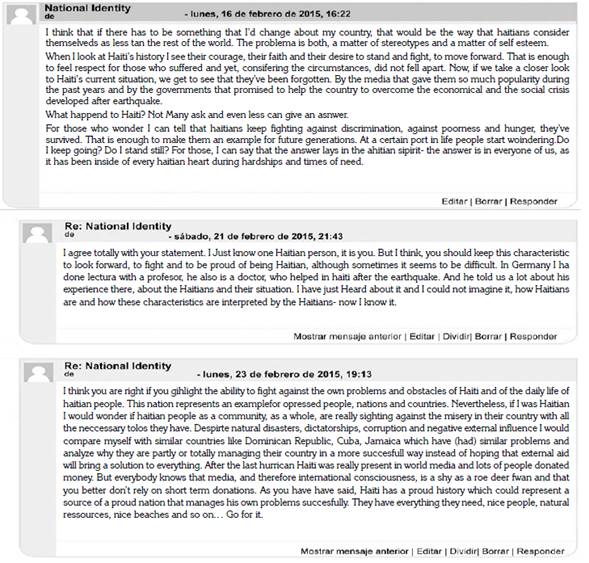

In Figure 6, a Haitian student highlights features of her country, her culture, and her national identity. She also makes an analysis of how historical occurrences and natural disasters have had a high impact on the perception that Haitian nationals have of themselves. It is also evidenced that her own perception of identity poses high value on the role that resiliency and endurance have on someone’s construction of identity. She highlights how hardship has not demeaned what she calls the ‘Haitian spirit’ referring to the capability of facing and eventually overcoming adversity.

In their replies, her classmates also make an analysis of her position and start connecting to the aspects presented in her post. In the first reply, her classmate recalls how he had previously heard of Haitians and how difficult it was for him to understand the ‘Haitian spirit’; but that after having the chance to meet a Haitian citizen, it was much easier for him to understand how they are and how they have managed to overcome difficulties.

130

National Identity , . . . .

do - lunes, 16 de febrero de 2015, 16:22

I think that if there has to be something that I’d change about my country, that would be the way that haitians consider themselveds as less tan the rest of the world. The problema is both, a matter of stereotypes and a matter of self esteem. When I look at Haiti’s history I see their courage, their faith and their desire to stand and fight, to move forward. That is enough to feel respect for those who suffered and yet, consifering the circumstances, did not fell apart. Now, if we take a closer look to Haiti’s current situation, we get to see that they’ve been forgotten. By the media that gave them so much popularity during the past years and by the governments that promised to help the country to overcome the economical and the social crisis developed after earthquake.

What happend to Haiti? Not Many ask and even less can give an asnwer.

For those who wonder I can tell that haitians keep fighting against discrimination, against poorness and hunger, they’ve survived. That is enough to make them an example for future generations. At a certain port in life people start woindering.Do I keep going? Do I stand still? For those, I can say that the answer lays in the ahitian sipirit- the answer is in everyone of us, as it has been inside of every haitian heart during hardships and times of need.

Editar | Borrar | Responder

Re: National Identity

d® - sábado, 21 de febrero de 2015, 21:43

I agree totally with your statement. I Just know one Haitian person, it is you. But I think, you should keep this characteristic to look forward, to fight and to be proud of being Haitian, although sometimes it seems to be difficult. In Germany I ha done lectura with a profesor, he also is a doctor, who helped in haiti after the earthquake. And he told us a lot about his experience there, about the Haitians and their situation. I have just Heard about it and I could not imagine it, how Haitians are and how these characteristics are interpreted by the Haitians- now I know it.

Mostrar mensaje anterior | Editar | Dividir| Borrar | Responder

Re: National Identity

de - lunes, 23 de febrero de 2015, 19:13

I think you are right if you gihlight the ability to fight against the own problems and obstacles of Haiti and of the daily life of haitian people. This nation represents an examplefor opressed people, nations and countries. Nevertheless, if I was Haitian I would wonder if haitian people as a community, as a whole, are really sighting against the misery in their country with all the neccessary tolos they have. Despirte natural disasters, dictatorships, corruption and negative external influence I would compare myself with similar countries like Dominican Republic, Cuba, Jamaica which have (had) similar problems and analyze why they are partly or totally managing their country in a more succesfull way instead of hoping that external aid will bring a solution to everything. After the last hurrican Haiti was really present in world media and lots of people donated money. But everybody knows that media, and therefore international consciousness, is a shy as a roe deer fwan and that you better don’t rely on short term donations. As you have have said, Haiti has a proud history which could represent a source of a proud nation that manages his own problems succesfully. They have everything they need, nice people, natural ressources, nice beaches and so on... Go for it.

Mostrar mensaje anterior | Editar | Dividirl Borrar | Responder

Figure 6. Students’ sample post.

In the following reply, although positive aspects were taken into account, the participant also makes a parallel among other Central American countries that have undergone similar situations to that of Haiti. He makes a more elaborate analysis and encourages the Haitian student to reflect upon the factors that have impeded Haiti to grow and become a more successful country.

It is evidenced how that particular task took students to a point in which they were able to reflect upon their origins, and actually start becoming interculturally effective (Spitzberg & Chagnon, 2009) when engaging in the analysis of a specific culture and the perceptions their classmates have on their own national identity. This also contributes to the achievement of other relational outcomes proposed

by Spitzberg (2012) which include “intercultural effectiveness, communication effectiveness, relational validation, intimacy, relational satisfaction, relational commitment, relational stability and uncertainty reduction” (p. 427).

The main goal of the elective courses offered by the DLC is to provide students with opportunities to improve not only their language skills but also to gather tools that can be used in real life and that can help them face challenges and overcome challenging situations successfully. The relational outcomes proposed by Spitzberg (2012) are not only “class strategies” that help students achieve a specific goal or complete a determined task. Students are expected to transfer all of these to their realities regardless their age, the major they have chosen or their country of origin. In addition, the relational outcomes focus on specific skills that future professionals should possess in order to perform well in their fields of expertise.

Although students’ posts and contributions were the main source of information, other activities were implemented in order to analyze students’ IC development and understanding. It must be highlighted that developing intercultural competences and intercultural awareness does not happen overnight; therefore, students’ appreciations and contributions should be taken into account for future replications of the experience. When asked about the best ways to develop intercultural competences, as part of an informal class survey, one of the participants highlights that:

Participant 5: The best form of develop intercultural competences is to study with students with different cultural backgrounds because it is the perfect form to get to know a person with different cultural attitudes and to learn from them.

(Informal Class Survey 1)

This student focuses on how important it is to have the opportunity to interact with others in order to learn from them. The words “learn from them” could be interpreted as a sign of awareness and mindfulness in terms of cultural differences. When asked about the topics they found most interesting, local students highlighted how important it is not only to know about other cultures around the world, but also to acknowledge differences inside their countries. In this regard, one of the participants asserts that:

Participant 2: A topic that was very interesting was “minorities” because usually a person relates intercultural studies with different countries. However, in one country more than one culture can exist. Because of that, in my opinion it is very important to maintain this topic. (Informal Class Survey 1)

Participant 6: I found it good that ethnic minorities were a topic, because they represent a different culture in the own country and are mostly ignored and discriminated against. This is a very good way to show existing but ignored or suppressed stereotypes and resentments. (Informal Class Survey 1)

Conclusions

Thinking of how to build, create, or set an intercultural classroom is still a puzzling issue to me. However, the experience discussed in this paper presented interesting challenges that led me to reflect upon several aspects that I had disregarded when planning previous courses. Up to this day, I continue to think that fostering students’ awareness regarding their intercultural competences and how important these competences have become, is a task that requires commitment and persistence from all those involved in the process in order to achieve common goals.

Developing intercultural awareness is not only about listing specific abilities and skills that intercultural speakers should possess. It is actually about offering chances in which students can develop the willingness to learn from others and consider that everyone has something to give, even if they do not belong to dominant groups of society. Offering opportunities for reflection, analysis, and for the development of interpersonal relationships becomes a key aspect when trying to develop and enhance students’ intercultural competences.

Differences exist in every context; students need to become interculturally competent, not only because

132

they might travel out of their countries someday, but also because foreigners might visit them. Due to the high ethnic and cultural diversity existing in our country, our students face intercultural experiences every day. Our capital city is a place that reunites people coming from all over the country in search of better opportunities and quality of life. It is of utmost importance that students become aware of this situation and learn how to respect and value differences.

In order to value difference, it must be considered that taboo topics such as discrimination, racism, indifference, etc., are controversial issues that happen on a daily basis in Colombia and all over the world; however, events related to these matters are overlooked and usually disregarded by society. Generalizations predominate regarding the kinds of populations coexisting in the Colombian territory; for example, it is no surprise that up to this day, people do not know about the existence of such diverse ethnic minorities in our country and, equally, it is still unknown for most of the population that indigenous communities need to be acknowledged and included in order to overcome several difficult situations which they face.

The intention of including the topic of ethnic minorities in specific countries was to create awareness of the misjudgments that take place when analyzing the situation of different kinds of populations not only in Colombia, but around the world. It is no secret that minorities are pigeonholed in negative roles in society. Those stereotypes should be studied in depth given that they are mostly false and bring harmful consequences for those peoples. In an ideal context, minorities should be regarded as communities that contribute to society in varied and diverse ways. Their wisdom should be regarded as an asset rather than as a burden. Minorities should not be forced to be inserted into a society that disregards their values and beliefs; however, this is the case of most minority groups around the world and this negative perception is leading to the disappearance of such populations.

As mentioned in the findings section, the topic of minorities was mentioned by students as one of the topics they considered key in order to analyze culture and identity. Regardless of the country, minorities exist all over the world and they face issues that are affecting and gradually destroying them. This particular topic, then, was used as a reason to generate discussion and to encourage students to connect to the reality of people living around them, people who are usually ignored by the dominant societies. Which leads us to think that choosing the right topics to be included in the course syllabus is of the most relevant factors in the success of an implementation aiming for the development of intercultural competences.

A final question arising from this reflective experience and which could be part of a second phase of the experience is: Is it possible to assess IC? Various models to assess IC have been proposed by several authors; however, such models have numerous limitations that would hinder their use depending on the context, participants, and content to be studied, among other factors. This is a fact that should be considered and studied more in depth in order to identify the most suitable method to evaluate, assess, or measure students’ intercultural competences.

In this particular experience, students took part in evaluation activities that helped the instructor in the identification of strengths and weaknesses, however; it should be considered that evaluating IC is not an easy task and therefore new strategies and alternatives should be constantly explored. Regarding this matter, Barletta (2009) asserts that:

Other important questions are whether the strategies proposed in class and used for solving or describing an intercultural encounter should be the ones considered correct or adequate; whether education should prescribe attitudes; whether intercultural competence should be evaluated separately from linguistic competence; and, lastly, how levels of intercultural competence can be defined. (p. 147)

The inclusion and assessment of IC should be regarded by higher education institutions around the world as a matter of high relevance due to the contexts in which students are most likely to be part of. Interculturality does not only happen when people travel abroad; nowadays, cultural differences are the order of the day, and learners must be prepared in order to be successful members of society capable of establishing effective interaction regardless of cultural backgrounds or national origins.

References

Arbeláez Jiménez, J., & Vélez Posada, R (2008). La etnoeducación en Colombia:

Una mirada indígena. Universidad Eafit, Escuela De Derecho Medellín. Retrieved from http://repository. eafit.edu.co/handle/10784/433

Baker, W (2012). From cultural awareness to intercultural awareness: Culture in ELT ELT Journal, 66(1), 62-70.

https://doi. org/10.1093/elt/ccr017

Barletta, N. (2009). Intercultural competence: Another challenge. PROFILE: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 11(1), 143-158.

Barnett, R. (1997). Higher education: A critical business. Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press.

Barreto, C. (2011). Development of intercultural competences in virtual learning environments. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte, 34, 194-219.

Bennett, M. J. (1986). A developmental approach to training for intercultural sensitivity.

International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10, 179-196.

https://doi. org/10.1016/0147-1767(86)90005-2

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communication competence. New York, NY: Multilingual Matters

Byram, M., Gribkova, B., & Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching: A practical introduction for teachers. Retrieved February 8th, 2016 from http:// lrc.cornell.edu/rs/roms/507sp/ExtraReadings/ Section0/Section0/uploads/File1235272745204/ InterculturalDimensionByram.pdf

Castro Suárez, C. (2009). Estudios sobre educación intercultural en Colombia: Tendencias y perspectivas. Revista Digital de Historia y Arqueología desde El Caribe, 10, 358-375.

Clavijo-Olarte, A., & González, A.R (2016). The missing voices in Colombia Bilingue: The case of Ebera children’s schooling in Bogotá, Colombia. In N. Hornberger (Ed.), Honoring Richard Ruiz and his work on language planning and bilingual education (pp. 431-457). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Cruz Arcila, F. (2007). Broadening minds: Exploring intercultural understanding in adult EFL learners. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 9, 144-173.

Deardorff, D. K. (2014). Some thoughts on assessing intercultural competence. Retrieved February 8th, 2016 from https://illinois.edu/blog/view/915/113048

Deardorff, D. K. (2016). How to assess intercultural competence. In H. Zhu (Ed.), Research methods in intercultural communication: A practical guide (pp. 120-135). West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Dervin, F (2015). On the dangers of intercultural competence. Program from Intercultural Competence in Communication and Education (ICCEd). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Universiti Rutra Malaysia.

Dervin, F (2016). How current understandings of language and culture (should) inform L2 pedagogy. Program from Fifth International Conference on the Development and Assessment of Intercultural Competence 2016. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona.

Fantini, A. E. (1995). Language, culture, and world view: Exploring the nexus. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 19, 143-153.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(95)00025-7

Fantini, A. E. (2009), Assessing intercultural competence: Issues and tools. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 456476). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fowler, W, & Lambert, P (Eds.). (2006). Political violence and the construction of national identity in Latin America. New York, NY: PALGRAVE MACMILLAN.

https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230601727

Griffith, D. A., & Harvey, M. G. (2000). An intercultural communication model for use in global interorganizational networks. Journal of International Marketing, 9(3), 87-103.

https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.9.3.87.19924

Holmes, P, & O’Neill, G. (2012). Developing and evaluating intercultural competence: Ethnographies of intercultural encounters. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 36(5), 707-718.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.04.010

House, J. (2007). What is an intercultural speaker? In E. A. Soler & M. P Safont Jorda (Eds.), Intercultural language learning and language use (pp. 7-21). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-5639-0_1

Howard-Hamilton, M. F, Richardson, B. J., & Shuford, B. (1998). Promoting multicultural education: A holistic approach. College Student Affairs Journal, 18, 5-17.

Ministerio Nacional de Educación (MEN). (2014, June). Proyecto de fortalecimiento de la educación media y tránsito a la educación terciaria 2014-2021: Marco de planificación para grupos étnicos (MPGE).

Muyuy Jacanamejoy, G. (2014). Interculturalizar la educación superior para interculturalizar la sociedad. Retrieved February 8th, 2016 from http://www. colombiaintercultural.gov.co/Documents/Cartilla-Seminario-Educacion-Superior.pdf

Reitenauer, V L., Cress, C. M., & Bennett, J. (2005). Creating cultural connections: Navigating difference, investigating power, unpacking privilege. In C. M. Cress, P J. Collier, & V L. Reitenauer (Eds.), Learning through serving: A student guidebook for servicelearning across the disciplines (pp. 67-82). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Spitzberg, B. H., & Chagnon, G. (2009). Conceptualizing intercultural communication competence. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 2-52). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Spitzberg, B. H. (2012). Axioms for a theory of intercultural communication competence. Annual Review of English Learning and Teaching, 14, 69-81.

Velez White, M. C. (1994). Políticas educativas sobre la interculturalidad-MEN. Men, (8), 3-28. Retrieved from http://www. mineducacion.gov. co/1621/ articles-85375_archivo_pdf.pdf

Recibido: 10 de mayo de 2017; Aceptado: 9 de enero de 2018

Resumen

El presente artículo tiene como objetivo compartir la experiencia obtenida al impartir un curso que apuntaba al desarrollo de Competencias Interculturales en estudiantes universitarios de una institución Colombiana de educación superior. Temas como las minorías, la identidad nacional y el racismo fueron incluidos en el programa del curso con el fin de sensibilizar a los estudiantes sobre la importancia de la interculturalidad. Con el fin de retratar las percepciones de los estudiantes acerca del curso y su influencia en el desarrollo de las competencias interculturales; se incluyó el análisis de los mensajes individuales y grupales de los estudiantes a los foros virtuales que se proponían semana a semana, además de sus respuestas a una encuesta individual. Los hallazgos sugieren que la interacción con personas procedentes de diversos contextos culturales aumenta la conciencia y la apreciación de la diferencia como un rasgo valioso y particular de la naturaleza humana.

Palabras clave:

antecedentes culturales, competencias interculturales, competencias, foros virtuales.Abstract

This article presents a pedagogical experience in which a course aiming at the development of intercultural competences was taught to university-level students in a Colombian higher education institution. Topics such as minority groups, national identity, and racism were included in the course syllabus in order to raise students’ awareness regarding the importance of interculturality. Data were collected from students’ individual and group posts to the virtual forums proposed every week. In addition, survey responses contributed to determining the influence of the course on the development of intercultural competences. Findings suggest that interacting with individuals coming from various cultural backgrounds increases one’s awareness and appreciation of difference as a valuable and particular asset of human nature.

Keywords :

cultural backgrounds, intercultural competences, skills, virtual fórums.Introduction

Intercultural competences (IC) is a trendy term that reunites all those ‘abilities’ that people should possess in order to interact appropriately and effectively with people from different cultural backgrounds (Bennet, 1986). However, thinking about the relevance of intercultural competences in a person’s life is what really matters when planning and teaching an interculturally-focused course.

Although multi- and intercultural education has been a topic of interest for several cultural and educational organizations in Colombia since the late 1990s, most of the research conducted focuses on the need for ethnic minorities and languages to be integrated into the existing educational system of our country which fails to acknowledge both their native languages and religious beliefs. It is widely accepted that intercultural education should focus on the needs of indigenous and ethnic minorities; nevertheless, as stated by Clavijo-Olarte and Gonzalez (2016) , “although Indigenous groups consider education as a relevant element to empower their social and cultural conditions, some curricular and educational contexts lack knowledge about Indigenous people’s ways of learning causing a mismatch between the community interests and schools” (p. 433).

Our country is still lacking development in terms of the conditions needed for the academic success of Indigenous communities. The most important aspect is that there should be a shift in the view of education that has shaped the development of educational policy. Due to the difficult conditions that surround the integration of Indigenous communities into the ‘dominant’ society, institutions perceive their roots and identity as obstacles for them to cope with the needs of ‘standard’ education. Guerrero (as cited in Clavijo-Olarte & Gonzalez 2016) states that “Colombia has a variety of languages that should be seen as resources and not as problems” (p. 432).

Although some of the literature addresses governmental attempts to include Indigenous communities into the “dominant” educational system; most of it addresses topics such as geography, history, and sociology. In a review of the literature, Castro Suárez (2009) asserts that there is limited work in terms of the educational situation of indigenous and afro communities, multiculturality, cultural diversity, and etnoeducación, (a term proposed by the Colombian Ministry of Education as a way to offer education to indigenous communities that addresses their specific needs; Arbeláez Jiménez & Velez Posada, 2008).

Up to now, the Colombian Ministry of National Education (MEN) has developed several initiatives regarding etnoeducación. According to the principles promulgated by the MEN, in documents such as “Politicas Educativas sobre la Interculturalidad” (Velez-White, 1994); etnoeducación should indeed respect minorities’ beliefs regarding cultural identity, religion, and language. Colombian ethnic minorities should at least be guaranteed, officially, that their children have access to primary education in order to acquire reading and writing abilities both in their native language and in Spanish; however, these basic rights have been openly neglected and “generally undervalued and associated with an invisible form of bilingualism” (De Mejia, 2006, as cited in Clavijo-Olarte & Gonzalez 2016, p. 435). In recent years, the MEN has studied many of these issues in relation to the situation of the minority languages as promulgated by “Proyecto de Fortalecimiento de la Educación Media y Tránsito a la Educación Terciaria 2014-2021 Marco de Planificación para Grupos Étnicos (Mpge; MEN, 2014),” but little attention has been given to issues such as teacher-training, learning and teaching materials, and social equity policies.

Government efforts have principally focused on the establishment of policies that acknowledge difference; such policies not only invite people to tolerate each other but to value the abundance of cultural heritage existing within a single country. It is highly important that government policies recognize that all members of the Colombian society, regardless of beliefs, race, or ethnic origin, play a fundamental role in the construction of national identity. According to Muyuy Jacanamejoy (2014) , the inclusion of intercultural competences in higher education is key to the establishment of a society in which persons respect and are aware of their rights and duties as individuals and as members of a community. Additionally, Muyuy Jacanamejoy (2014) highlights the significance of having higher education institutions embrace IC as a group of competences that needs to be included in the academic curricula of all majors. What is more, efforts should be made to create institutions that, despite being mainly focused on the development of IC, are still capable and willing to interact with other fields of knowledge to satisfy both indigenous communities and Colombian citizens in general in order to reaffirm national identity.

Regarding this issue, Barreto (2011) argues that although some institutions have made efforts to initiate the inclusion of IC into their programs, the development of IC is not contained within the group of competences that must be learned by students. What is more, educators do not count on a formal curriculum that addresses IC explicitly either in virtual or in online programs.

As higher education has been the context of my 10 years of experience as a language educator, I have had the chance to teach not only language courses but also diploma courses whose focus (as stated in the syllabi) is to develop IC in students. These courses have been developed over several years, and, for over three years, I have been in charge of adapting previous programs and creating new ones in order to offer the academic community (national and international students from over 20 majors) alternatives to practice their English skills and to learn about other cultures.

In spite of these efforts, it was evidenced that, differently from international students, national students were not aware enough of the relevance that IC have for both their professional and personal development. As stated by Cruz Arcila (2007) , “we usually tend to perceive our own culture as the appropriate way of looking at and doing things, and of perceiving reality” (p. 146). This was, sadly, the most common attitude assumed by the Colombian participants of the course before being exposed to activities planned in order raise their awareness and appreciation of difference.

The fact that international students are more aware of the relevance of IC was continuously evidenced throughout the implementation of the mentioned diploma courses. Activities such as debates, virtual forum discussions, and in-class presentations (among other activities) substantially demonstrated how those international students counted on more tools as to perform successfully in social and cultural backgrounds which were considerably different from their own.

The issue described above triggered my interest in researching the acquisition and development of intercultural competences in Colombia, particularly at the level of higher education. It has been my interest to find out whether and how the implementation of these diploma courses contributes to the development of IC on the one hand, and, on the other, how these courses maintain, and hopefully increase such awareness in international students. However, creating an environment in which national and international students’ intercultural abilities can actually develop has not been an easy task. Cruz Arcila (2007) also emphasizes the fact that:

Currently, we are facing many instances of cultural contact that may lead to situations of conflict if we are not prepared to deal with this. Nowadays, language learners need to be provided, not only with linguistic tools, but also with cultural knowledge for them to be prepared for intercultural communication. (p. 148)

When conflict takes place, classroom environment can become harsh and result in students refraining from expressing their opinions and insights. It is of utmost importance to train students in the development of competencies that allow them to understand, comprehend, and respect others. However, it is difficult to determine how respectful our students are regarding a specific aspect, but it is possible to assure their exposure to controversial topics that motivate students to think critically and reflect upon unknown matters.

What are Intercultural Competences?

Several studies on the definition of the term intercultural competences have been conducted over the years, given its relevance especially in higher education where “students from different contexts come together to live and learn” (Holmes & O’Neill, 2012, p. 707). However, taking a look at various studies, it is clear that discrepancies abound among the authors who, according to their perspectives, value some characteristics more than others.