DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.16732Published:

2021-09-30Issue:

Vol. 23 No. 2 (2021): July-DecemberSection:

Theme ReviewCritical Pedagogy Trends in English Language Teaching

Tendencias de la pedagogía crítica en la enseñanza del idioma inglés

Keywords:

pedagogía crítica, pensamiento crítico, enseñanza del inglés, revisión de literatura (es).Keywords:

critical pedagogy, critical thinking, English language teaching, literature review (en).Downloads

References

Arcila, F. C. (2018). The Wisdom of Teachers’ Personal Theories: Creative ELT Practices From Colombian Rural Schools. Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 20(2), 65-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.67142 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.67142

Bastos, M. D. A. A., & Ramos, M. A. S. (2015). Tecnologias e competências de pensamento na aprendizagem da língua estrangeira-inglês. Revista e-Curriculum, 13(3), 589-609. https://revistas.pucsp.br/index.php/curriculum/article/view/24732/17668

Bolaños, F., Florez, K., Ramírez, M., & Tello, S. (2018). Implementing a community-based project in an EFL rural classroom. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 20(2), 274-289. http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/22487085.13735 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.13735

Chun, C. W. (2018). Critical pedagogy and language learning in the age of social media? Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, 18(2), 281-300. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1984-6398201811978 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-6398201811978

Contreras-León, J. J., & Chapetón-Castro, C. M. (2016). Cooperative Learning With a Focus on the Social: A Pedagogical Proposal for the EFL Classroom. HOW Journal, 23(2), 125-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.23.2.321 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19183/how.23.2.321

Cortés-Rozo, E. J., Suárez-Vergara, D. A., & Castañeda-Trujillo, J. E. (2019). Exploring Students’ Context Representations by Using Songs in English With a Social Content. Profile Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 21(2), 129-141. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v21n2.77731 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v21n2.77731

Echeverri-Sucerquia, P. A., Arias, N., & Gómez, I. C. (2014). Critical Pedagogy in English Teacher Professional Development: The Experience of a Study Group. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 19(2), 167-181. http://dx.doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v19n2a04 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v19n2a04

Echeverri-Sucerquia, P. A., & Pérez-Restrepo, S. (2014). Making sense of critical pedagogy in L2 education through a collaborative study group. Profile Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 16(2), 171-184. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n2.38633 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n2.38633

Freire, P. (2005). Pedagogía del oprimido (2nd ed.). Siglo XXI Editores.

Giroux, H. (2003). Pedagogía y política de la esperanza. Teoría, Cultura y enseñanza. Amorrortu Editores.

Gómez, P. A., & Cortés-Jaramillo, J. A. (2019). Constructing sense of community through community inquiry and the implementation of a negotiated syllabus. GIST Education and Learning Research Journal, 18, 68-85. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.432 DOI: https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.432

Gutiérrez, C. (2015). Beliefs, attitudes, and reflections of EFL pre-service teachers while exploring critical literacy theories to prepare and implement critical lessons. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 179-192. http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a01 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a01

Kim, M. K., & Pollar, V. A. (2017). A modest critical pedagogy for English as a foreign language education. Education as Change, 21(1), 50-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/492 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/492

Kemmis, S. (1993). El curriculum: Más allá de una teoría de la reproducción. Ediciones Morata.

Mahmoodarabi, M., & Khodabakhsh, M. R. (2015). Critical Pedagogy: EFL Teachers' Views, Experience and Academic Degrees. English Language Teaching, 8(6), 100-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n6p100 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v8n6p100

Malebese, M. L. (2019). A socially inclusive teaching strategy: A liberating pedagogy for responding to English literacy problems. South African Journal of Education, 39(1), 1514. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39n1a1514 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39n1a1514

Mayaba, N. N., Ralarala, M. K., & Angu, P. (2018). Student voice: Perspectives on language and critical pedagogy in South African higher education. Educational Research for Social Change, 7(1), 1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2018/v7i1a1 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17159/2221-4070/2018/v7i1a1

Mizan, S. (2019). Transnational imaginaries of emerging identities in English teacher education in a period of accommodation to social change in Brazilian Higher Education. Trabalhos em Linguística Aplicada, 58(1), 177-194. https://doi.org/10.1590/010318138654076456311 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/010318138654076456311

Ortiz, J. Z. P., & Duarte, E. G. (2014). Bridging the gap between theory and practice in a BA program in EFL. HOW journal, 21(1), 122-137. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.21.1.19 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19183/how.21.1.19

Palacios-Mena, N., & Chapetón-Castro, C. M. (2014). The use of English songs with social content as a situated literacy practice: Factors that influence student participation in the EFL classroom. Folios, 40, 125-138. https://doi.org/10.17227/01234870.40folios125.138 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17227/01234870.40folios125.138

Pennycook, A. (1994). The cultural politics of English as an international language. Longman Group Limited

Quintero-Polo, Á. H. (2019). From utopia to reality: Trans-formation of pedagogical knowledge in English language teacher education. Profile Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 21(1), 27-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v21n1.70921 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v21n1.70921

Rincón, J. A., & Clavijo-Olarte, A. (2016). Fostering EFL learners' literacies through local inquiry in a multimodal experience. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 18(2), 67-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n2.10610 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n2.10610

Sardabi, N., Biria, R., & Golestan, A. A. (2018). Reshaping Teacher Professional Identity through Critical Pedagogy-Informed Teacher Education. International Journal of Instruction, 11(3), 617-634. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2018.11342a DOI: https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2018.11342a

Sharma, B. K., & Phyak, P. (2017). Criticality as ideological becoming: Developing English teachers for critical pedagogy in Nepal. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 14(2-3), 210-238. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2017.1285204 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2017.1285204

Stenhouse, L. (1984). Investigación y desarrollo del currículum. Ediciones Morata.

Tadeu da Silva, T. (1999). Documentos de identidade: Uma Introdução às teorias do currículo (2nd ed.). Autêntica Editorial.

Varani, S. B., & Kasaian, S. A. (2014). On the effects of doing CDA term projects on Iranian graduate TEFL students' critical pedagogic attitudes. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 4(6), 1207-1213. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.4.6.1207-1213 DOI: https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.4.6.1207-1213

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 3 de agosto de 2020; Aceptado: 26 de agosto de 2021

Abstract

This article presents a literature review regarding the latest trends in the inclusion of Critical Pedagogy (CP) in English Language Teaching (ELT) in different countries worldwide and in Colombia, considering its different regions. A review of different articles was conducted by considering four databases that include two regional and two international journal directories in both English and Spanish. The papers were analyzed and discussed from a mixed approach in which four keywords were tracked, and factors such as geographical distribution, as well as the way in which CP was implemented in the studies, were identified. The results of this query show that CP in ELT is an emerging trend, especially in countries where political, social, and economic inequality remains. In the same way, the findings suggest that different strategies regarding curricula analysis, the role of teachers and students as social subjects, among others, have been carried out in order to foster the understanding of this theory and its application and considerations in real-life contexts. Attempts to implement CP in English classes have proven to be meaningful experiences and constructive at developing critical thinking strategies in students.

Keywords

critical pedagogy, critical thinking, English language teaching, literature review.Resumen

Este artículo presenta una revisión de literatura de las últimas tendencias en la inclusión de la Pedagogía Crítica (PC) en la enseñanza del inglés en diferentes países del mundo y en regiones de Colombia. Se llevó a cabo una revisión de varios artículos considerando cuatro bases de datos que incluyen directorios de revistas regionales e internacionales tanto en inglés como en español. Los artículos fueron analizados desde un enfoque mixto en donde se rastrearon cuatro palabras clave y se identificaron factores como la distribución geográfica y la manera en que se implementó la PC en los estudios. Los resultados de esta búsqueda sugieren que la PC en la enseñanza del inglés es una tendencia emergente, sobre todo en países en los que aún hay desigualdad social, política y económica. De la misma manera, los hallazgos revelan la implementación de diversas estrategias relacionadas con el análisis del currículo, el rol del maestro y del estudiante como sujetos sociales, entre otros, para promover el entendimiento de esta teoría, así como las consideraciones y aplicaciones en contextos de la vida real. Los esfuerzos de implementar la PC en las clases de inglés demuestran ser experiencias significativas y enriquecedoras en el momento de desarrollar estrategias de pensamiento crítico en los estudiantes.

Palabras clave

pedagogía crítica, pensamiento crítico, enseñanza del inglés, revisión de literatura.Introduction

Education and Society

Educational theories and practices have been strongly influenced by context needs. Thus, each society establishes what is more important and urgent to approach. In most current societies - as in the case of the Colombian context - economic models determine what students must know and, more importantly, what they must be able to do. In a neoliberal economic system, education is not a service but a good that is sold, and it aims at creating qualified labor force. Authors like Freire (2005) differ from this vision, call into question the presupposed purpose of education, and claim that emancipation must be key for social transformation. Giroux (1988) and McLaren (1984) argue that this could be reached through the permanent questioning of the kinds of subordination through school discourse in which students belonging to minorities, (in terms of nationality, gender, sexual orientation, race, etc.) access to knowledge that is understood as a ‘common heritage’ which, in reality, is information that has been transmitted for years through the legacy of the dominant groups. This legacy in Western societies is mainly white, patriarchal, and sexist. The authors’ stances evidence the conception of education as a political and sociocultural practice. Critical Pedagogy (CP) emerged from this perspective, and, even though it is not a perfectly bounded territory, what we do know about CP is its capacity to relate education and social situations.

As in education in general, the field of English Language Teaching (ELT) has evolved according to context needs. Consider the case of the Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) approach that prevailed over other methods when globalization hit the market, wherein fluency became more important than perfecting grammar structures. In the same way, it is necessary to ask ourselves how ELT is contributing to our current context necessities and particularities. Unlike critical thinking, which seeks to develop higher-order reasoning and foster reflexive and autonomous thinking in a single person, CP seeks the emancipation of human societies through education.

Pennycook (1994) , with regard to Critical Pedagogy in ELT, points to the urgency of understanding what it means to learn English in current global power relations. The author states that teachers must be conscious of the political dimension in ELT and suspect those who claim the neutral nature of English. In this sense, teachers must evaluate the significance of their teaching practices in the reproduction of social inequalities. In addition, adopting CP in the educational context is considering a new paradigm for teachers’ professional activity; it is thinking about a way of academic life in which the educational process considers for whom, why, how, when, and where activities are performed. These academic practices approach the acquisition of self-awareness, which facilitates the construction of new knowledge and the transformation not only of the subjects’ particular contexts, but also of the social-educational context.

This state-of-the-art article is presented within the framework of a research project named Implementación y seguimiento del enfoque sociocrítitico en el área de inglés de la Fundación Universitaria Católica Lumen Gentium [2] , which seeks to identify the conception and implementation of CP by EFL teachers in their classes. To this effect, the identification of the tendencies in the inclusion of CP in ELT contexts is necessary. It is also necessary to understand how CP is being implemented and how it is impacting educational subjects.

Methodology

To construct this literature review, four databases were selected: the first two were SCOPUS and Dialnet, as they include an international overview of the published literature regarding our research topic; Redalyc and SciELO were also considered, given that an exploration of the studies that have been carried out in the regional context was required. Four concepts related to our research analysis unit were traced. These included Critical Pedagogy and combinations such as Critical Pedagogy-Foreign Languages, Critical curriculum-English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and Critical PedagogyEnglish. In the case of regional databases, the concepts in Spanish were searched, and, to expand the search scope, the terms Currículo crítico, as well as its accepted synonym sociocrítico, were included.

The initial query delivered 40 articles that were subjected to a deeper examination. An analysis grid was designed considering the bibliographic information, as well as the objectives, approaches, methodologies, and results of the articles in the corpus. The final query was focused on the timelapse of five years (2014-2019) in order to get an updated view of the implementation of CP in EFL contexts. The articles were also grouped according to the continent, country, and, in the case of Colombia, city or department. After analyzing the search results, the articles that were irrelevant for the study were discarded. In this way, a corpus of 22 research articles that were related to Critical Pedagogy or Critical Curriculum and Foreign Languages, English, or English Language Teaching was consolidated.

Results

During the exploration of the databases, it was found that the concept of Critical Pedagogy was mentioned in 1.007 articles in Scopus, 2.278 in Dialnet, 456 in SciELO, and 490 in Redalyc. Likewise, the combination Critical PedagogyEnglish generated 111 results in Scopus, while 79 articles were registered in Dialnet, five in SciELO, and 415 in Redalyc. The final search included the terms Critical pedagogy-English as a Foreign language, which had an occurrence of 21 times in Scopus, 24 in Dialnet, 3 in SciELO, and 415 in Redalyc.

These findings show that, even though CP has been widely studied around the world, its inclusion in the field of English as a foreign language is still emerging. Despite the results, a more detailed selection process was conducted by excluding the articles related to areas of knowledge outside of the scope. This final selection resulted in 22 articles. In the following section, the results are shown, which are discriminated by geographical location.

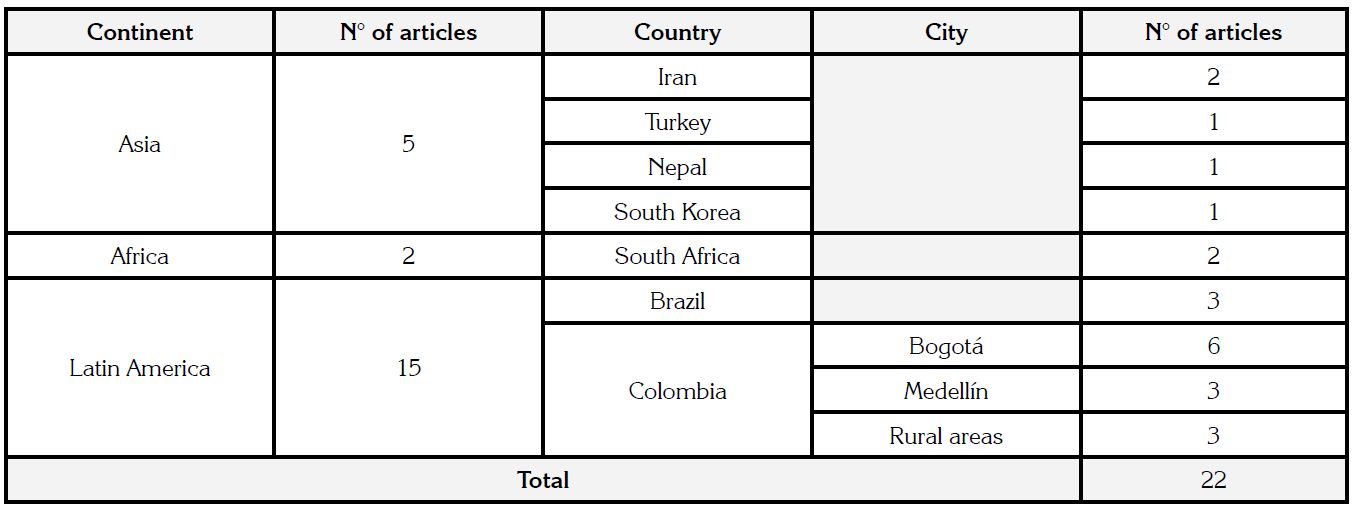

Table 1: Critical Pedagogy studies

In Table 1 the studies are classified by continent, country, and, in the case of Colombia, city.

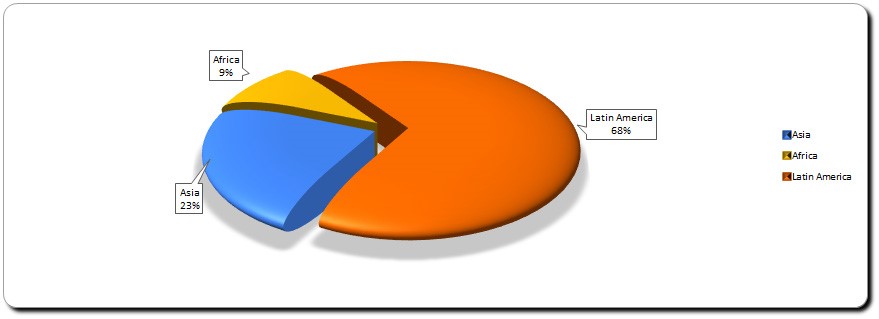

The corpus shows that most of the articles published within the last five years in our area of interest prevail in Latin America, whereas Africa has a lower participation in the subject (only 9% of the sample). Although Latin America’s 68% stands out, studies carried out in Asia have an important contribution in the sample constituting the 23% of it. It is interesting to notice that European and North American countries did not have any representation in the query conducted in the four databases.

Figure 1 graphically represents the proportions in which continents have contributed to the understanding of CP in foreign language teaching. While it is evident that Latin America and Asia comprised more than the 90% of the sample, it is necessary to explore why this field has been hardly studied in other continents. It is assumed that this tendency is due to the historical roots upon which CP sets its foundations, which has its origins in the proposals of the Brazilian pedagogue, Paulo Freire. Moreover, CP seeks to ameliorate the particular needs of countries where social, political, and economic injustice and inequality are generally present, i.e. Latin American countries.

Asia

As for the Asian continent, two of the research studies were completed in Iran. The first is a case study led by Varani and Kasaian in 2014 . This study was completed with 43 graduate TEFL students. It aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of working with critical discourse analysis projects as a way to promote CP in teachers. In order to do so, the participants were tested through an attitude questionnaire before and after the course. The findings showed that these types of projects influence the attitudes of the students by reshaping their identity as teachers. On the other hand, Mahmoodarabi and Khodabakhsh (2015) published a qualitative study that involved around 400 teachers of EFL at different institutions with diverse academic backgrounds and years of experience. The objective was to explore Iranian EFL teachers’ beliefs and tendency to implement CP in their teaching praxis. Through a scaling questionnaire, it was evidenced that the higher the educational background and longer experience was, the more aware teachers were regarding critical pedagogy.

Figure 1: Percentage of studies carried out per continent

Additionally, there was a Turkish qualitative case study that examined the role of a teacher education program. The project was based on the principles of CP, and the purpose was to observe its influence in novice EFL teachers’ professional identity construction. Sardabi, Biria, and Golestan (2018) found that there were two main changes in participants’ professional identity. The study established that the participants were transformed from compliant and with a narrow view of EFL teaching, to having a more developed voice and adopting a humanistic conception of EFL.

Sharma and Phyak (2017) discussed how criticality was constructed and implemented for EFL teacher development in Nepal. The study consisted of two phases. First, teachers designed EFL materials considering cultural practices in their country that were viewed as controversial by foreigners. Then, a five-hour workshop was developed to discuss the possibilities of implementing such materials in an EFL class. The authors prompted dialogues that concerned their and their students’ sociopolitical issues. The design of materials included controversial topics such as child labor and gender disparity in education, among others. During the conversations, the participants identified how the dowry, for instance, was a cultural practice that was hard to change but needed to be addressed. They also discussed how enriching it would be to adopt such approach in English education.

Another case study in South Korea in 2017 evaluated the reactions of the inclusion of CP in the curriculum. It proved that the role of educators as ‘meddlers in the middle’ generated some resistance and its implementation could be riddled with difficulties. Kim and Pollar (2017) executed this research by using reflective research journals and interviews.

In the Asian continent, there is an emerging trend of including CP issues in ELT teacher development programs. Most of the case studies presented suggest that, although there is an evolution in the participants’ identity and attitude towards teaching after the experiences with CP in their teaching practices, it is quite difficult to transform the traditional paradigms. It is also very interesting that the intention of applying CP in this continent is attributable to the need of changing the system and the context.

Africa

Both studies found in the African continent were developed in South Africa. In the first one, Mayaba et al. (2018) recognized the importance of multilingualism as a skill that students should have. The authors recommended that students’ opinions ought to be considered in the construction of curriculum to avoid the reproduction of inequalities by imposing a hegemonic language. On the other hand, there was a participatory action-research led by Malebese (2019) , which implemented Socially Inclusive Teaching Strategies (SITS) in order to improve listening and speaking skills in students of fourth, fifth, and sixth grade in a public rural school. Results demonstrate how these strategies contributed to overcome the students’ difficulties in these abilities. Thus, African studies in our subject suggest the importance given to students’ voices and concerns regarding their educational processes. It is enthralling how researchers are aware of the importance of including students’ feelings in curriculum design.

Latin America

It is intriguing how the Latin American countries stood out. However, according to the consulted databases, only two out of the 20 countries in this continent have conducted studies concerning the issue under study: Brazil and Colombia.

A Brazilian case study performed by Bastos and Ramos (2015) intended to examine the impact of cognitive tools and critical thinking processes on EFL learning. The results demonstrated important differences in the students’ accomplishments, and they evidenced an increase in the reasoning ability and the effective use of communicative and digital tools. Although Bastos and Ramos’s article is about the development of critical thinking, it focuses more on the metacognitive strategies students can construct while learning English, rather than on the building of an emancipatory reasoning.

Chun (2018) addressed the possibilities of incorporating CP in social media. The author examined how students faced the language and discourses found in both online and offline spaces, and how these spaces attempt to build hegemonic social representations. The author concludes that it is necessary to expose our students to varied discourses in a critical way, so that they become active subjects that aim to construct a democratic society.

Finally, Mizan (2019) conducted a study with an ethnographic approach to investigate the cultures and literacies surrounding students. This study emerged from an academic writing course for EFL teachers that aimed to develop both their writing skills and their critical thinking. The students were requested to discuss and write about certain topics in light of experiences of other contexts they had heard of by different means (e.g. the Internet). According to the author, the texts produced by students revealed reflections on the topics that involved interacting with media and resources that go beyond national borders. For example, some students were interested in the educational approach to gender practices in foreign countries like Sweden, as well as in the social aesthetics of gender, feminism, among others. The author concludes that these transnational literacies can be considered to be an expansion of critical literacies based on critical thinking, as they extend our capacity to read and interpret the world from positions that are culturally alien to our own, and also that these experiences enriched the classroom as a learning space.

Colombia

Colombian research experiences that included CP in EFL were mostly developed in major cities such as Bogotá and Medellín. However, it is also very intriguing that rural areas and less populated departments such as Tolima have started to walk the path of the implementation of CP in EFL contexts.

In the case of Bogotá, six studies were conducted during the last five years. Four of them focused on students’ experiences regarding CP in a foreign language context, and two of them worked with teachers’ beliefs and professional experiences regarding the inclusion of CP in their field of knowledge.

For example, Cortés-Rozo et al. (2019) analyzed the representations students made about their own context after working with some songs in English with social content. From the analysis, some categories such as Feelings of Loneliness, Physical and Verbal Mistreatment, Problem Management, among others, resulted as representations of the students’ closest context. The results also proved how this kind of activity encourages students to talk about their own realities. In the same way, Palacios-Mena and Chapetón-Castro (2014) also carried out a study with social-content songs to examine the factors that influence forty 11th grade students’ participation while using this material. The findings, which were obtained from classroom observation and student participation, showed the way in which songs in a particular context can motivate students to be reflective, as well as how teaching English can go beyond the grammar to give meaningful experiences and promote students’ critical role in society.

Rincón and Clavijo-Olarte (2016) conducted a study addressing the ways in which community inquiries generate possibilities for students to explore cultural issues in their neighborhoods by using multimodality. In this qualitative study, the authors discussed the role of these community inquiries in the creation of relations between students and their own contexts. The data were collected through class observations and recordings of class debates to have a general and individual perspective of the participants, who were 10th graders from the lowest socioeconomic levels. The results revealed that students’ communities represent opportunities for the creation of meaningful English learning spaces in order to transform the traditional language practices into ways to communicate what students really care about. In the same way, the results show how community inquiries also locate students in a role with a critical view inside their own community.

The last study focused on the development of CP among students in Bogotá in a four-year period. It was carried out by Contreras-León and ChapetónCastro (2016) with a group of 7th graders in an EFL class in a public school. This research sought to foster students’ interaction in the classroom using cooperative learning principles on topics related to students’ social aspects. The contents were addressed in three cycles, where students had the opportunity to activate their previous knowledge about the reality of the topic under study in order to analyze it and link it to the new ideas they came up with. This research showed that it was also possible to articulate the EFL syllabus with the students’ realities in order to promote critical reflections. In addition, it revealed how the vision of a language as a social practice and interaction through cooperative strategies are useful to encourage social awareness.

On the other hand, Quintero-Polo (2019) developed a study about future English teachers’ trans-formations of knowledge regarding language education. This qualitative study used the conception and reflections of five future teachers in diaries and interviews that constituted the data to be analyzed. The findings revealed that the implementation of trans-formations mediated by pedagogical and research agendas offered opportunities to develop awareness related to social and cultural issues in language education. In the same way, according to the author, the concept of language education was transformed by adopting a reflective approach, where the participants assumed a more critical role.

Finally, Ortiz and Duarte (2014) centered their study on the theoretical principles on the field of research in a bachelor’s program of a Colombian public university. The objective of the study was to reflect about the program’s syllabus in order to encourage students and teachers to understand how, through the research component of the program, it is possible to link the theory with the pedagogical practice with the intention of having transformative and meaningful practices in an EFL educational context. The authors concluded that constant group reflection is a useful tool to evaluate the syllabus and academic processes in the program to avoid gaps in contents. In the same way, after this revision, the participants included problematic questions in their subjects to make students engage with the exploration of alternatives in their classroom in order to promote transformative teachers and practices.

In the second largest Colombian city, Medellín, only three studies regarding CP in ELT contexts have been carried out during the last five years. All of them have a focus on teachers’ professional development and the process of implementing CP in their English teaching practices.

Echeverri-Sucerquia et al. (2014) explored the experience of a study group comprising six language teachers (French and English) of a public university in Medellín. The purposes of the group were to continue their teaching professional development and explore the possibilities of CP in language teaching. The group’s methodology consisted of different readings and discussions of theoretical texts about CP and experiences of CP in ELT contexts. The narratives of the participants were recorded and then transcribed by themselves. Results showed that this experience led participants to recognize themselves as humans and socio-political beings. It was also an opportunity to re-construct the meaning of education in L2. At the end of the experience, the group proposed a Humanizing Education (HE) in which students are at the center of the process, contents are related to students’ realities and contexts, and collaborative work and Project Based Learning are used as strategies.

Echeverri-Sucerquia and Pérez-Restrepo (2014) report their experience in the conception and understanding of CP in a study group of foreign language teaching professionals mentioned in the previous article. The authors first characterize the participants of the study group and describe the differences in their experience, academic background, and personal beliefs.They also relate different levels of familiarity with CP and describe it as an abstract concept that is difficult to understand given its complex language. It was through discussions and different strategies such as guiding questions, mind-mapping, sketches, etc., that leaders in the group guided this issue. Conclusions in the paper show that sense-making of the theory involved two simultaneous and interlinked processes: an individual understanding of the theory and the collaborative construction of meaning. Both enterprises are equally important and necessary in the assimilation of new concepts. The authors point out some conditions necessary to make sense of theory: improvement of reading habits, recognition of time-investing in the understanding of theory, creation of a positive learning environment, and the use of experiences to contextualize the theory ( Echeverri-Sucerquia and Pérez-Restrepo, 2014 ).

Gutiérrez (2015) conducted research seeking to explore how three pre-service English teachers understood and attempted to implement Critical Literacies (CL) in their teaching practices. Initially, the participants were exposed to literature about CL by different authors; this phase was developed in a controlled environment (the classroom) and different discussions and reflections were illustrated based on the readings. Then, the design of lesson plans seeking the promotion of CL in their future students was carried out. During the third phase of the study, the researcher observed the participants’ classes and could evidence their understanding of the implementation of CL in their classes. The results showed that each participant dealt with the challenge in a different way, but they all managed to have the experience of teaching an English class while fostering critical thinking in their students. Two common results for all three of them were the worry of not being able to cover the contents in the curricula and the opinion of the parents. Two participants were worried about the level of English proficiency needed for adapting a CL approach and the workload it implied. At the end of the study, only one of them was willing to continue promoting a critical thinking in the students.

Other regions in Colombia have also sought alternatives in ELT and have explored CP fostering through community-based projects and other creative strategies. The following three studies were conducted in Colombian rural contexts, something very interesting that is subject of analysis in the next section. Arcila (2018) conducted a study as part of a bigger research project that aimed to assess English teaching in rural Colombia and the challenges the context represents for teachers. The study explored seven English teachers’ narratives, perspectives, and teaching practices. The participants were located in different regions of Colombia, in the departments of Boyacá, Cundinamarca, Casanare, and Nariño. Class observations and interviews with the teachers revealed that, without even being aware of post-method theories, teachers’ creativeness and flexibility compiled the use of L1 as a means to reach L2 abilities, the contextualization of resources to motivate students, the use of available technology, and the design of their own material. The conclusions of this study suggest that teachers attempt to negotiate between external demands and the reality of their educational contexts. They are also proof that, even in difficult socio-cultural contexts, teaching practices are valuable.

Bolaños et al. (2018) carried out a project in a rural municipality of Santander, Colombia. The project aimed to implement a pedagogical intervention that fostered the development of critical thinking in a group of 36 9th graders at a public school. Five pre-service teachers designed a curriculum with Project Based Learning, whose goal was to improve the sense of community in students. The curriculum consisted of the development of two units that considered both the rural context and the standards of the Ministry of Education. By the end of the four-month intervention, students felt more engaged in their learning processes; English as a school subject resulted more enjoyable, and they felt empowered after classes.

Gómez and Cortés-Jaramillo (2019) carried out an English course in a public school located in a rural area of Planadas, Tolima by implementing a community-based project and a negotiated syllabus. First, a survey was conducted to assess particular needs. Then, the group made a proposal about the topics and activities that could make part of the course syllabus. At a third stage, the design of a curricular proposal that integrated both students’ requests and the language policy mediated by the BLR (Basic Learning Rights) was created. Finally, the implementation and assessment were made by the teacher through observations and adjustment of some issues during the learning process. The findings suggest that involving students in course design raised awareness about the purpose and importance of learning English. Also, working under a community-based project encouraged students to address real community problems and take actions to solve them.

Discussion

The tendencies in the implementation of CP in ELT evidence two paths that researchers and academics have undertaken to achieve it: teacher professional development and the implementation of different strategies in the classroom to foster critical thinking in students.

Studies around the world emphasize the understanding of CP by means of teacher professional development workshops and programs. The compiled experiences prove that strategies such as study groups, material design, curricula analysis, and reflection upon their own teaching practices led participant English teachers to develop critical thinking and understand the principles of CP and CL.

However, the evolution of teachers in this regard does not come without its own struggles. As pointed by Stenhouse (1984) resistance to change is present because of conflicts of power, practicality, and psychological issues. Teachers find it difficult to apply CP principles because they also need to cope with curriculum content, favor parents’ demands, and deal with context difficulties such as lack of resources, overcrowded classrooms, and language policies.

Nevertheless, the above-mentioned struggles can be addressed in different ways. Kemmis (1993) , for instance, mentions the importance of considering students’ needs and social problems in the curricula. This does not imply the need to neglect national language policies or interfere with the standards set by the institution regarding the expected levels of communicative competences in students. Indeed, Tadeu da Silva (1999) poses the question of identity in curriculum as central and more important than content itself. Some of the teaching experiences showed that involving cultural issues, controversial topics, and community problems in the syllabus facilitated not only the development of critical thinking in students, but also motivated them to learn the language since the topics were meaningful for them.

The real struggle that CP represents in teachers’ lives is related to their own capacity of being critical and their willingness to change. Although some issues regarding quality of education as a workload, the number of students per class, and the availability of materials and teaching tools need to be solved and are out of teachers’ possibilities; a deeper conscious, critical stance needs to be developed for teachers to become agents of transformation.

Another visible tendency in the implementation of CP in ELT is the students’ experiences. Most of the study cases showed effectiveness. Positive experiences resulted in the improvement of both English language teaching as a social practice and the development of critical thinking capacities in students. Strategies such as a negotiated curriculum, the use of social-content songs or general contents related to students’ realities, cooperative learning tactics, the use of L1 to reach L2, among others, were key to foster students’ reflection upon their own contexts. This constitutes an important step towards the development of a true emancipation of students’ thinking within a language learning context.

It is interesting to highlight how, in these studies, EFL education breaks with the traditional paradigms of second language acquisition theories in which cognitive and structuralist aspects prevail and the communication aim is just communication itself; now, these theories make their way to the inclusion of elements such as students’ cultural identity, emotional factors, and beliefs that foster the transformation of a society and regard the foreign language as a sociocultural practice and a tool to reflect, transform, and re-build society.

Despite these results, it is worth asking why there are not enough studies of this type in other Latin American countries or even in Colombia, where a lack of education opportunities and social inequality prevail. It is also very intriguing not to have any occurrence of studies of this nature in Europe and North America. Probably, the five-year time lapse restriction for the query of the articles may have led to the exclusion of studies in these places. It is also necessary to reflect about the sample and whether it actually shows a trend, or if education with a colonial perspective - i.e. non authentic material, non-contextualized topics, standardized tests, dominant culture contents, etc. - is still leading the way in Latin American education.

Conclusions

This literature review revealed that Critical Pedagogy is still an emerging theoretical trend in the field of ELT and EFL education, as English teachers and researchers are developing different mechanisms to understand it and implement it in their classrooms. The presented experiences provide different strategies in which educators are managing the meaning-making of CP in English teaching environments. The approaches could be divided into two big categories: teacher professional development and implementation of CP, critical thinking, or CL in the classroom from the students’ perspectives.

The sample revealed that CP is an intriguing element in countries where political, economic, social, and educational inequality remains. Hence, the need to involve CP as an axis of education for social change. Also, transforming teachers’ professional identity, building critical thinking in students, and awareness of the need for a change in the teaching paradigm of English according to our contexts needs are some of the profits that these experiences have delivered. Nevertheless, some struggles have been also evidenced, especially in the area of English teachers’ conceptions and the transformation of their identities.

References

Notes

Metrics

License

Copyright (c) 2021 Brenda Portilla Quintero, Jennifer Herrera Molina

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.