DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n1.8403Published:

2016-05-11Issue:

Vol 18, No 1 (2016) January-JuneSection:

Teaching IssuesMeaning making and communication in the multimodal age: ideas for language teachers

Construcción de significados y comunicación en la era multimodal: ideas para profesores del lenguaje

Keywords:

relación intersemiótica, construcción de significado, modo de comunicación, multimodalidad, recursos semióticos (es).Keywords:

meaning making, multimodality, mode of communication, intersemiotic relationship, semiotic resources (en).Downloads

References

Baldry, A. & Thibault, P. J. (2006). Multimodal transcription and text analysis. London; Oakville, CT: Equinox Pub.

Bateman, J. A. (2008). Multimodality and genre: A foundation for the systematic analysis of multimodal documents. Basingstoke; New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Beetham, H., Mcgill, L., & Littlejohn, A. (2009). Thriving in the 21st century: learning literacies for the digital age (LLiDA project). The Caledonian Academy, Glasgow Caledonian University: UK.

Borges, V. Are ESL/EFL software programs effective for language learning? Ilha do Desterro, 6, 19-73.

Busuu.com Retrieved from http://www.busuu.com/.

Cloonan, A. (2010). Multiliteracies, Multimodality and teacher professional. Australia: Common Ground Publishing.

Cook, V. (2001). Using the first language in the classroom. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 57, 402-423.

Cook, V. (2008). Second Language Learning and Language Teaching. London: Arnold.

Cousins, C. (2013). Serif vs. Sans Serif Fonts: Is One Really Better Than the Other? Retrieved from http://designshack.net/articles/typography/serif-vs-sans-serif-fonts-is-one-really-better-than-the-other/

Eggins, S. (2004). An introduction to systemic functional linguistics. New York: Continuum.

Ellis, R. (2008). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gee, J. P. (2001). New times and new literacies - Themes for a changing world learning for the future. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Proceedings of the learning conference 2001, 5 (pp. 1-20). Greece: Learning Conference & Common Ground.

Halliday, M. & Hasan, R. (1986). Language, context and text: Aspects of language in a social-semiotic perspective. Geelong: Deakin University Press.

Halliday, M.A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic. The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Hawisher, G. & Selfe, C. (2000) (Eds.). Conclusion: hybrid and transgressive literacy practices on the web. In Global Literacies and the World Wide Web (pp. 277-290). London: Routledge.

Hodge, R., & Kress, G. (1988). Social semiotics. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press in association with Basil Blackwell, Oxford, UK.

Howatt, A.P.R. (1984). A history of English Language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jewitt, C. (2006). Technology, literacy and learning: A multimodal approach. London: Routledge.

Jewitt, C. (2008). Multimodality and literacy in school classrooms. Review of Research in Education, 32(1), 241–267. doi:10.3102/0091732X07310586

Jewitt, C. (2009) (Ed). An introduction to multimodality. In The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis (pp. 14-27). Abingdon: Routledge.

Jewitt, C. & Kress, G. (2003) (Eds.). Introduction. In Multimodal literacy (1-18). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Kalantzis, M. & Cope, B. (2008). Introduction: Initial development of the ‘multiliteracies’ concept. In S. May and N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education, Vol.1: Language policy and political issues in education (pp.195–211). New York: Springer Science+Business Media LLC.

Kress, G. (1997). Visual and verbal modes of representation in electronically mediated communication the potentials of new forms of texts. In I. Snyder (Ed.), Page to screen: Taking literacy into the electronic era (pp. 53-79). London: Routledge

Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the new media age. London: Routledge.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality a social semiotic approach to communication. London: Routledge Falmer.

Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading images: the grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.

Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse. London: Arnold.

Lankshear, C., Peters, M., & Knobel, M. (2002). Information, knowledge and learning: Some issues facing epistemology and education in a digital age. In M. Lea & K. Nicoll (Eds.), Distributed learning: Social and cultural approaches to practice (pp. 16-37). London: Routledge.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2000). Techniques and principles in language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Learning English Online.com (LEO). Retrieved from http://www.learn-english-online.org/

Machin, D. (2007). Introduction to multimodal analysis. London: Hodder Arnold.

Mayer, R. E. (2001). Multimedia learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O'Reilly, T. (2005). What is Web 2.0. Design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. Retrieved from: http://oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html?page=5

O’Halloran, K. L., & Smith, B. A. (2011) (Eds.). Multimodal studies. In Multimodal studies: Exploring issues and domains (pp. 1-13). New York: Routledge.

Paivio, A. (1986). Mental representations: A dual coding approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

Paivio, A. (2007). Mind and its evolution: A dual coding theoretical approach. Mahwah, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Richards, J. & Rodgers, T. (2001). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

The New London Group (Cazden, C., Cope, B., Fairclough, N., Gee, J., Kalantzis, M., Kress, G., Luke, A., et al.) (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60–92.

van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing social semiotics. London: Routledge.

van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Towards a semiotics of typography. Information Design Journal+ communication design, 14(2), 139-155.

Warschauer, M. & Healey, D. (1998). Computers and language learning: an overview. Language teaching, 31, 57-71.

Warschauer, M. (2010). Digital literacy studies: Progress and prospects. In M. Baynham & M. Prinsloo (Eds.), The future of literacy studies (pp. 123-140). Houndmills, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Warschauer, M. & Grimes, D. (2007). Audience, authorship, and artifact: The emergent semiotics of Web 2.0. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 27, 1-23.

Waugh, L. & Álvarez, J. A., Do, T, H., Michelson, K., & Thomas, M. (2013). Meaning in texts and contexts. In K. Allan (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics (pp. 613-634). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Winet, K., Jacobson, B., & Tucker, M. (2014) (Eds.). A Student’s Guide to First-Year Writing, 35th ed. Plymouth: Hayden-McNeil Publishing.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n1.8403

TEACHING ISSUES

Meaning making and communication in the multimodal age: ideas for language teachers

Construcción de significados y comunicación en la era multimodal: ideas para profesores del lenguaje

José Aldemar Álvarez Valencia1

1 Escuela de Ciencias del lenguaje, Universidad del Valle, Valle del Cauca. Colombia. jose.aldemar.alvarez@correo.univalle.edu.co

Citation/ Para citar este Artículo: Álvarez, J. (2016). Meaning Making and Communication in the Multimodal Age: Ideas for Language Teachers. Colomb. Appl.Linguist.J., 18(1), pp 98-115

Received: 11-Apr-2015 / Accepted: 23-Feb-2016

Abstract

Contemporary societies are grappling with the social changes caused by the current communication landscape and complex textual habitats. To account for this complexity in meaning-making practices, some scholars have proposed the multimodal approach. This paper intends to introduce the core concepts of multimodality including semiotic resources, modes of communication, and intersemiotic relationships. It provides practical applications of multimodal analyses by examining printed and digital pages of educational materials. The final section proposes a set of recommendations to integrate the multimodal perspective in language classes, highlighting the need to make students aware of the new dynamics of meaning making, meaning negotiation, and meaning distribution.

Keywords: intersemiotic relationships, meaning making, mode of communication, multimodality, semiotic resources

Resumen

Las sociedades contemporáneas están enfrentándose a los cambios sociales provocados por el paisaje de comunicación actual y las complejidades de los hábitats textuales. Para dar cuenta de la complejidad en la construcción de significados, algunos académicos han propuesto el enfoque multimodal. Este escrito tiene la intención de introducir los conceptos básicos de la multimodalidad, tales como recursos semióticos, modos de comunicación y relaciones intersemióticas. Proporciono aplicaciones de análisis multimodal en páginas impresas y digitales de materiales educativos. La sección final propone un conjunto de recomendaciones para integrar la perspectiva multimodal en las clases de lenguas, destacando la necesidad de sensibilizar a los estudiantes sobre la nueva dinámica de creación, negociación y distribución de significados.

Palabras clave: relación intersemiótica, construcción de significado, modo de comunicación, multimodalidad, recursos semióticos

Introduction

Are we communicating in a different way today than we did three decades ago? The answer is yes; however, this might not be the right question to ask. Rather, we should inquire about the causes of such a change in the communication landscape and what characterizes current texts. There is one overarching question embedded within the previous two questions and that constitutes a locus of research and academic debate: How has the current communication landscape shaped the ways we make meaning and ultimately communicate? If communication is one of the principal channels of socialization and identity construction (Duff & Talmy, 2011), then it follows that shifts in the way societies communicate and access information have ramifications for education. Along with the turbulence produced by these shifts come challenges to conventional social institutions, e.g. schools (Hawisher & Selfe, 2000) and social activity (Kress, 2003). Therefore, it is imperative to conceptualize new theories of meaning and communication (Jewitt, 2008; Jewitt & Kress 2003; Kress, 2003).

The advent of computers and other technological devices is considered the foremost source of the recent change in the communication landscape. Kress (1997), Warschauer (2010), Gee (2001), and The New London Group (1996) posit that the processes of globalization and internationalization have boosted technological development (e.g. computers, the Internet), and thus, the upcoming of the electronic era which has moved literacy into the digital age (Jewitt, 2008; Kress, 1997, 2003). Kress lists three aspects that paved the way for a new conception of literacy and communication in light of the electronic era.

First, we have experienced a "trend towards the visual representation of information which was formerly solely coded in language" (Kress, 1997, p. 66). We have seen how the dominance of the book has given way to the dominance of the screen. Thus, we have become visual cultures. This is a phenomenon that can be observed daily as we navigate the Internet or we use digital devices. Most digital interfaces are designed so that we are required to read less verbal language and instead we are prompted to read more audiovisual messages. A look at the navigational interface of smartphones or websites such as Facebook, Flicker, or YouTube exemplifies the displacement of writing as the primary medium of dissemination in many domains of communication to favor image. Digital devices evince the transition from language-centered texts (monomodal texts) towards multimodal texts (Cloonan, 2010; Jewitt, 2006; Kress, 2003; Lankshear, Peters, & Knobel, 2002).

Second, language studies have been impacted by 'the multimodal turn.' Contemporary technologies facilitate the combination of various modes of communication such as image, sound, written language, and animation among others. This is the reason why several scholars have acknowledged that all communication is multimodal (e.g. Kress, 2010; Machin, 2007; O'Halloran & Smith, 2011). The turn to the multimodal is in stark contrast with language studies that have primarily foregrounded oral and written modes of communication. Language studies have downplayed the role of other semiotic resources such as proxemics, chronemics, gesture, gaze, spatial distribution2 and other elements that interplay in communication exchanges and contribute to meaning making.

Third, the digital era has given way to the development of convergent technologies. Kress (1997, 2003, 2010) and Kalantzis and Cope (2008) show that unlike past technologies in which electronic devices (e.g. radio, TV, telephone) were designed to perform one main task, new devices are designed in such a way that different technologies converge. If we look back in time, items such as phones, TV, computers, radios, photographic cameras, video games, and newspapers were associated to certain rituals performed at certain times and at specific physical spaces. For example, the family would gather in the living room to listen to the radio or watch the news show. Today, all of these items converge in a single device in which communication and information are accessible, mobile, and ubiquitous: the cellphone. The circulation of these devices impacts communication due to their ubiquity, availability, and ease of use (Beetham, Mcgill, & Littlejohn, 2009).

What can be concluded initially is that the new communication landscape has shaping effects on how people design, negotiate, and disseminate meaning; therefore, another approach to language and communication is necessary—an approach that is heuristic and looks at the different elements that part-take in meaning making and sign production. I am referring to the multimodal approach. The main purpose of this paper is to the highlight the multimodal nature of communication and the need for teachers and students to be aware of this. As the title indicates, the discussion and reflections in this article are targeted to language teachers in general, including teachers of first or second languages. This rationale explains the selection of the texts analyzed below: a textbook mainly used to teach composition to American students and samples from two websites for second language learners of French and English. In what follows, I intend to introduce the multimodal perspective and some of its major concepts. In the second part, I demonstrate how to examine multimodal texts along with some recommendations about how to integrate this perspective in language classes.

What is Multimodality?

The multimodal perspective advances a new conception of language and communication. However, to understand to what extent it constitutes a shift in the way we conceive of communication, a digression is in order to briefly examine the western linguistic tradition. It is well known that the linguistic mode of communication (oral and written language) has dominated language studies for the last millennium and a half. The linguistic mode has become specialized among the other modes of communication by being considered the main carrier of meaning (Kress, 2003, 2010). This view of communication gave rise to verbocentric and typographic cultures. Several disciplines have spent a great deal of time scrutinizing the oral and written modes of communication. The two major theories in linguistics, Generative Linguistics and Functional Linguistics, both have emphasized the study of oral and written language. In turn, a host of disciplines have developed with the purpose of studying language structure and language use, including text linguistics, speech act theory, conversation analysis, critical discourse analysis, discursive psychology, ethnography of communication, interactional sociolinguistics, all of which are rooted in different disciplines such as sociology, philosophy, anthropology, and psychology (Waugh, Álvarez, Do, Michelson, & Thomas, 2013). Despite the dominant role of verbal language, there are other approaches gravitating in the periphery of language and communication studies; for example, semiotics, film theories, visual analysis theories, which examine meaning making beyond the verbocentric and typographic views. In fact, the multimodal perspective draws on elements of all of these approaches.

Multimodality is a response to the challenges that linguistic description is facing in light of the changes in the way texts are designed, produced, and disseminated. Multimodality has been defined as "the approaches that understand communication and representation to be more than about language, and which attend to the full range of communicational forms people use—image, gesture, gaze, posture and so on—and the relationships between them" (Jewitt, 2009, p. 14). The multimodal approach is grounded in a social semiotic view of language and communication. Semiotics studies the processes and structures whereby meaning is made in social spaces (Hodge & Kress, 1988; Kress, & van Leeuwen, 2001). That is to say, it wonders about the elements that play out when we make meaning and how we represent those meanings in communication. The multimodal approach provides the tools to examine texts by breaking them into their basic components and by understanding how they work together to make meaning.

Central Concepts in Multimodality

The multimodal perspective adopted in this article draws on the concept of social semiotics that derives from the work of Halliday (1978) and his functional view of language. Halliday claims that texts need to be seen as contextually situated signs. In doing so, language (text) and its interrelation to social environments (context) determine the potential for users to make meaning, a process that Halliday (1978; Halliday & Hasan, 1986) has termed the meaning potential of language. For Halliday (1978), language serves three general functions in communication; it helps us express and represent our experience in the world (ideational metafunction), it creates relations between producers and receivers of messages (interpersonal metafunction), and it allows us organize texts to form coherent wholes (textual metafunction).

Following the Hallidayan thought, Kress and van Leeuwen (1906, 2001), Jewitt (2006), and Machin (2007) have developed the multimodal social semiotic view of communication. One central concept in this multimodal approach is semiotic resources. According to van Leeuwen (2005) semiotic resources are:

the actions, materials and artifacts we use for communicative purposes, whether produced physiologically – for example, with our vocal apparatus, the muscles we use to make facial expressions and gestures – or technologically – for example, with pen and ink, or computer hardware and software – together with the ways in which these resources can be organized. (p. 285)

The grouping of certain semiotic resources is called of communication or modes of meaning. The New London Group (1996; see Figure 1) describes modes of communication as resources that permit the design of meanings. They propose the following modes: inguistic, audio, spatial, gestural, and visual mode. Another concept in multimodality is intersemiotic relationships. It refers to how meaning is distributed across modes. In other words, how the combination of modes of communication add up to the general meaning of a text. As an illustration, if we think of a piece of advertisement, every single element in it has been designed to contribute to a general meaning: the color, the spatial distribution, the written message, and the images all combine to generate a specific message.

Doing Multimodal Analysis: An Example

This section presents an example of analysis of a multimodal text, particularly, a textbook page. The purpose is to illustrate the steps that I propose to examine multimodal texts as a way to raise awareness of the multimodal nature of texts and communication in general. By no means is it my intention to suggest that language teachers need to engage in such granular analysis of the texts they use with their students. However, it is important that teachers recognize the analytical possibilities in multimodal analyses. As I discuss in the section Recommendations to Integrate the Multimodal Approach in Language Classes below, there are several pedagogical strategies that will help teachers as well as students to engage in the analysis of multimodal texts. The intention is to broaden students understanding of the ways meaning is made by recognizing the structure of texts and the possible meanings that they construct.

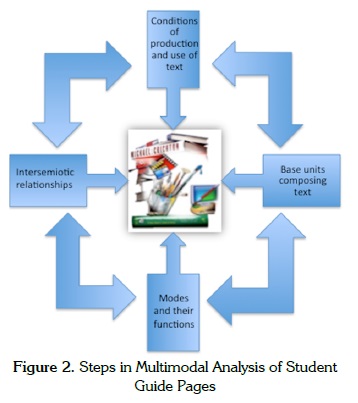

To conduct a multimodal analysis, I have devised a four-step process (see Figure 2) that I will follow below in analyzing a textbook section3. One experience common to most educators is the use of textbooks. With the passing of time, textbooks have relied more on audio-visual elements. Textbooks include icons, drawings, graphics, photographs, colors, sounds, video recordings; they even include supplementary material that can be accessed on the web. Textbooks are full-fledged multimodal texts for which most educators, coming from verbocentric educational traditions, have not been trained to manipulate. One important step in understanding the nature of the textbook as a multimodal composition is to examine pedagogical principles behind textbook design.

Examining conditions of production and use

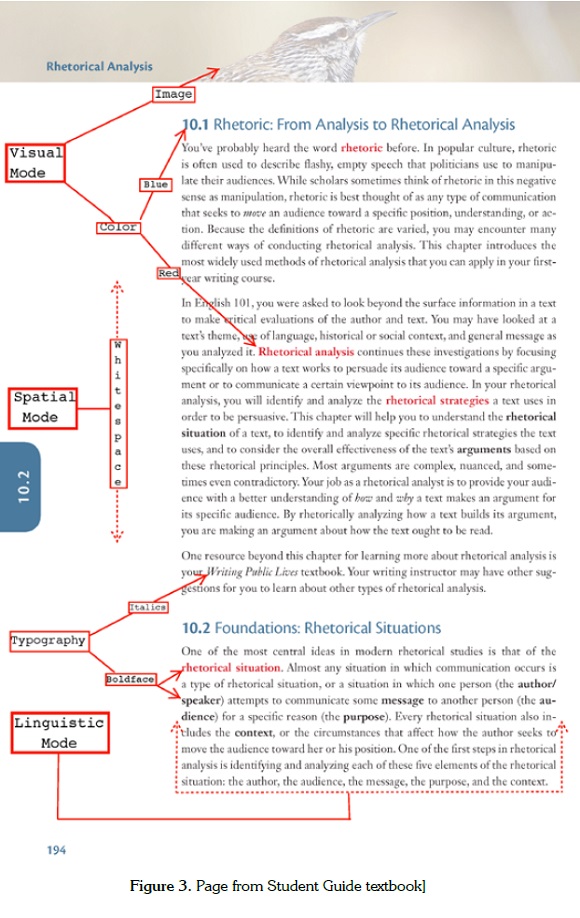

To examine the pedagogical principles of textbook design, I have chosen one page from one of the textbooks that I used in teaching first-year English Composition in the US: named A Students' Guide to First Year Writing (SG) (Haley-Brown, Lee, & Rodriguez, 2011). (See Figure 3). It is common to think that a "regular" written page might not be a good example of a multimodal text. Nonetheless, a closer look reveals that a written document is composed of a variety of semiotic resources. At the outset of a multimodal analysis4, the first question to ask is, what are the conditions of production and use of the text under scrutiny?

Part of this answer was introduced above: the genre of this text is that of a textbook. The book is edited by the Writing Program of the University of Arizona for instructors to employ in their English composition classes. The textbook is primarily targeted to American college students, although it is also used in ESL classes.

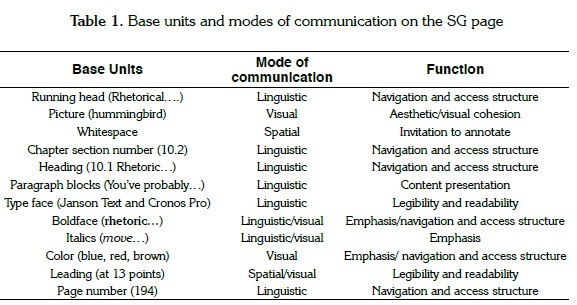

Identifying base units

The second step in the analysis is to identify the base units that compose the text. A base unit according to Bateman (2008) is "everything which can be seen on each page of an analysed document" (p. 110). Table 1 introduces the main base units and modes encountered on the page, starting from the upper left side of the SG page (see Figure 3).

Identifying modes of communication and their meaning-making functions

The third step involves identifying the modes of communication that are at play for each base unit. Additionally, it is necessary to define the specific meaning-making function(s) of the modes of communication in the multimodal composition. Three modes of communication articulate primarily on this written page: linguistic mode, visual mode, and spatial mode, each one involving several affordances (see Table 1).

The first is the linguistic mode of communication that performs the heaviest semiotic work on the page. The linguistic mode is not only employed to introduce contents (e.g. paragraph blocks), it also functions as a device that helps readers navigate and access the contents of the page. To do this, written language first appears as a Running head ("Rhetorical Analysis") at the upper left-hand corner of the page that informs readers that they are browsing through the chapter on rhetorical analysis. Some of the affordances of written language such as headings ("10.1 Rhetoric from Analysis to Rhetorical Analysis"), section numbers ("10.2"), page number ("194"), boldface text (e.g. rhetoric, rhetorical analysis, author") and italics ("move…Writing Public Lives") are instrumental in helping readers locate contents with ease and establish relationships between concepts and sections within the chapter. Some of these base units such as boldface text and italicized language play a twofold role. They are typographic resources that are associated with the linguistic mode of communication, but they also play a visual role because their display conveys paralinguistic information (Bateman, 2008). Both boldface in any color and italicized language communicate different levels of salience and emphasis: Red (e.g. rhetorical situation) is used for superordinate concepts and black boldface for subcategories under those superordinate concepts (e.g. author/speaker, message, purpose). In the explanation presented in SG, concepts such as author, message, and purpose constitute components of the rhetorical situation of a given text.

Typeface is another affordance of the written form of the linguistic mode and, as van Leeuwen (2006) states, it has become a "means of communication in its own right" (p. 142). The main purpose of typeface is legibility and readability. Within the area of typography, typeface or font family focuses on letter structure with the intention of communicating messages as clearly as possible while providing a pleasurable aesthetic depiction. Without delving into the broad and rich area of typography, it can be said that SG draws primarily on two types of fonts: Cronos pro for titles and Janson Text for paragraph blocks. Both typefaces belong to the family of sans serif. Cousins (2013) asserts that the "mood and feelings most associated with sans serif typefaces are modern, friendly, direct, clean and minimal" (para. 4), features that will sit well on a page that will be read by freshman students. On the other hand, typeface relies heavily on the concept of leading or line spacing, which in this case is at 13 points, a little larger than single space. Along with the vertical layout of paragraphs, typographers also study the space between characters, that is, how words and characters stretch out horizontally (termed kerning). As can be seen on the page above, both typefaces effectively adjust the space between characters to facilitate readability. In short, a look at paragraph blocks shows that the effective arrangement of the elements just mentioned adds up to a harmonious design that is legible, readable, and also aesthetically agreeable.

The visual mode of communication manifests in different ways in the SG page. The first visual element that draws the reader's attention is the pictorial image of a bird. The question that arises is: What is the purpose of this picture? It is traditional that the book cover of SG determines the general visual theme of the book. For this edition, the theme was the hummingbird. The fact that the hummingbird appears in several sections of the book aims to create cohesion and coherence with the general visual theme of the book. Likewise, it is undergird by an aesthetic motif. The visual mode also relies on the affordances of color and in the written page it is used for emphasis, but at the same time to differentiate and codify the role and status of certain concepts. On the page, blue is used for headings (e.g. "10.1 Rhetoric: From Analysis to Rhetorical Analysis") and, as mentioned above, red highlights the conceptual importance of certain words and phrases (e.g. "rhetoric… rhetorical analysis…rhetorical strategies"), while black is utilized to describe and explain the superordinate concepts presented on the page. Thus, color is deployed to indicate the order of things and to create flow around a composition (Machin, 2007). From the perspective of page layout, there is clearly an aesthetic intention since the page is designed to combine several elements (image, paragraph blocks, color, broad margins) in a way that is pleasurable to the eye. From this, we can deduce that the page itself becomes a visual unit in the eye of the viewer.

The final mode encountered on the page is spatial distribution that manifests through the layout of the page. Layout is paramount in the design of a multimodal page because it guides the reader through the document, but most importantly as research has shown, "page elements and their organization strongly influence how readers interact and interpret the documents that contain them" (Bateman, 2008, p. 22). The SG page is divided into 5 modules (M), a first horizontal module at the top of the page composed by the picture of the bird and three vertical modules that consist of the broad whitespace on the left, followed by the text block in the center, a narrow module on the right and, finally, a horizontal module at the bottom of the page occupied by the page number (see Figure 4). One of the modules that catches the readers' attention is the left vertical module. A reader would wonder why the left side margin is quite broad. This design choice is explained in terms of the nature of the publication: a textbook, which has an educational intent. Thus, the whitespace is a space for students to write their reactions to the contents in M3. Making this space available for annotations draws on the western writing pattern where the left-to-right and top-to-bottom directionality is predominant.

The page follows the ideal/real composition structure proposed by Kress and van Leeuwen (1996). These terms describe a metaphorical relation between what is at the top of a composition 'ideal,' connoting what is idealized or promised, and what is at the bottom 'real,' referring to what is more realistic such as factual information and the everyday. The ideal/real structure is commonly used in everyday advertisements in which what is idealized or promised (image of a beautiful woman) is placed at the top, while what is real is placed at the bottom: actual image of product, a description, or its price. On the SG page, the ideal/real relation is established between the picture and the orthographic language (Figure 4). An interesting intersemiotic relationship builds in between these modes of communication. On the ideal sphere the upper module consists of a picture that embeds the running head "Rhetorical Analysis," located on the left corner. In a metaphorical way, this message provides meaning to the image in which a thoughtful hummingbird is looking up as though it is engaged in a process of examination or analysis. While we know that the ideal appeals to what is imaginary or emotional through aesthetics for example, the real sphere below the picture of the bird (M3) is in contrast because it involves an explanation about what rhetorical analysis is, along with examples and factual information.

Establishing intersemiotic relationships

The fourth step in the analysis answers the question: What meanings does the text make? The previous analysis allowed us to see that the base units that compose a page embody different functions and thus convey individual meanings. Although identifying the individual semiotic force of each element is relevant, multimodality emphasizes the analysis of the meanings that stem from the intersemiotic relationships between the modes and their base units. In doing such analytic work, the language metafunctions provide interesting insight to identify how ideational, interpersonal, and textual meanings of multimodal texts are shaped.

Ideational Meanings

How does the SG page represent meanings about the world? A common answer is that it talks about rhetoric. Indeed, the subject matter content constitutes the main ideational meaning enacted in this text. Nonetheless, there is more to say about meaning making on the page. This multimodal composition makes three main meanings.

First, as suggested above, it conveys meanings related to rhetorical analysis. It uses written language (typography- typeface, boldface, italics, numerals, and color) to introduce and establish relationships (order and hierarchy) between concepts.

Second, it enacts meanings related to the structure and navigation of the textbook and its contents. That is, it provides a navigation path that informs readers what the main themes of the chapter are through running heads, headings, and section numbers that are codified through blue color. The multimodal composition informs readers about the main concepts or key words in the chapter through the use of boldface and color. These key concepts act as pointers or locators that relate to the back-of-the-book index.

Third, it conveys meanings related to the identity of the reader, to the act of reading, and to the text genre. The page does this by combining spatial distribution (e.g. space to make annotations and navigational devices such as section numbers), linguistic (e.g. typeface, boldface, numerals, use of colloquial tone and, non-technical explanations) and visual modes (picture, color, layout). All these modes with their affordances construct the idea of an inexperienced reader, someone who needs to be provided with tools to develop good reading practices such as annotating, focusing on main concepts, and being able to navigate through the contents of a book. In turn, these elements point at the type of genre of this publication that is a textbook for freshman. Given the projected identity of the reader and the genre, it makes sense to think that there is a strong pedagogical intent through the multimodal composition of the book that purports to not only convey subject matter content, but also enact and model certain reading practices and strategies. This analysis indicates that the semiotic affordances deployed helped both to convey content and to shape the content in a way that is more understandable and accessible to freshman.

Interpersonal Meanings

How does the SG page use semiotic resources to enact addresser and addressee positions and relations? We already pinpointed above that through several semiotic resources, SG positions users as readers that are acquiring basic concepts on the subject matter of rhetorical analysis and who are in the process of developing sound reading strategies such as annotating. At first sight, a reader would think that the textbook replicates the traditional asymmetrical interpersonal orientation in which the writer of a textbook is constructed as the knower while the student or reader appears as a novice. Although, as it has been shown above, the compositional structure of SG to some extent appeals to this interactional orientation, it attenuates it through the tone that undergirds the entire multimodal composition. The tone of the text attempts to attain affective involvement with the reader by creating an informal and friendly textual environment. In doing this, not only does it draw on aesthetic values (appealing layout, colors, images), but also on affordances of the linguistic mode of communication such as point of view, informality, and lexical and grammatical choices.

The authors of SG favor the second person point of view to directly address the reader: "You've probably heard the word rhetoric before" (M3, para. 1). By drawing on the second person point of view, the authors are able to insert a casual and conversational tone, personalize the writing, and make an interpersonal connection with their audience. This informal tone is heightened by the use of contractions ("you've"), low introduction of technical terms (low lexical density and complexity), lack of citations, and an effort to explain in simplified language concepts such as rhetoric or rhetorical situation. For instance, while dictionaries or other textbooks typically define rhetoric as 'the art of persuasion,' SG introduces a definition that appears to be more understandable to freshman: "rhetoric is best thought of as any type of communication that seeks to move an audience toward a specific position, understanding, or action" (M3, paragraph 1). Unlike more formal and technical texts that are characterized by grammatical complexity (Eggins, 2004), this page of SG is easy to read because, for example, it is mostly written in active voice (only two examples of passive voice are found) and makes little use of nominalizations: "provide your audience with a better understanding" (M3, paragraph 2). In brief, this page of SG draws on several semiotic resources to enact interactions such as inviting students to write annotations. It expresses positions and attitudes toward who is addressed, mainly, a casual and friendly pedagogical orientation, and toward what is being represented–the area of rhetoric which is presented as accessible and engaging to the extent that readers are positioned as practitioners of rhetorical analysis: "Your job as a rhetorical analysts is..." (M3, paragraph 2).

Textual Meanings

How is the SG text discursively coherent and situationally relevant? Let us begin by discussing how coherent the SG page is in relation to the context of situation in which the text is employed. The sample page evidences that the textbook's semiotic design (navigation patterns, layout) and the use of language (informal, descriptive, simplified) clearly cohere with what is expected of a pedagogical material targeted to students of a first year composition class. The question whether the page is discursively coherent has been touched upon indirectly above. Multimodal texts reach cohesion and coherence through intersemiotic connections in multiple ways. At the most basic level, typography contributes to establish coherence because as Machin asserts, "the same font can be used throughout a document to signify something is of the same order" (2007, p. 93). For instance, in SG a constant pattern is the use of Cronos pro and Janson Text typefaces; the former is employed for titles in font size 14 and the latter for paragraph texts in font size 9. Color also acts as a cohesive and coherence marker since it distinguishes conceptual hierarchy and contributes to facilitating navigation through the page and the book overall. Image and written text are connected semiotically if we agree with the proposition that the ideal sphere (picture of bird evoking examination or analysis) and the real sphere (the presentation of what rhetorical analysis) imply a sort of semantic association (Eggins, 2004).

At the level of the written text, lexicogrammatical resources serve to attain a textual orientation by connecting what is written to the rest of the text. The SG page attains coherence mainly by drawing on devices such as thematic development. One example is the first paragraph that introduces the word rhetoric and uses it repeatedly throughout the text to create thematic development since in each clause it is described or qualified in different ways, giving the text a sense of cumulative development. Other devices such as reference and lexical organization are employed to create coherence and cohesion. Reference is used to establish connections between words, phrases, sentences or ideas that appear in the text. For example, in the third clause, in the first paragraph the demonstrative "this" followed by the nominal group "negative sense as manipulation" acts as an anaphoric reference connected coherently to the antecedent "flashy, empty speech that that politicians use to manipulate their audiences" (see Figure 3). Lexical coherence is attained through repetition of words such as "rhetoric," "rhetorical analysis," and "you" and through the inclusion of words or nominal groups that are common in the semantic field of rhetoric: speech, politicians, audience, manipulate, position, move, and rhetorical analysis.

One may wonder how being able to identify the features of texts presented above would benefit language teachers and learners. Language learning is a process of meaning making in which different modes of communication intervene beyond the linguistic mode. Traditionally, language teaching has overlooked the multimodal nature of communication and meaning making, privileging the linguistic mode as the main meaning carrier (Kress, 2000). The common assumption is that learners enter the language classroom to learn how to use the linguistic system of a certain language to communicate. My view is that language classrooms should enable students to use all semiotic resources available, including oral and written language, image, space, and body language to learn to make meaning in the target language (L1 or L2). It is in this context that the analytic exercise presented above makes sense. Although teachers and students do not need to engage in such detailed descriptions as presented above, they should be aware that all elements playing out in a textual environment such as a textbook page, video clip, website page, or conversation make meaning. This approach clearly aligns with an ecological understanding of language learning that poses that:

the learner is immersed in an environment full of potential meanings... The learner in his or her environment is engaged with understanding all aspects of interpreting and understanding human interaction, and not only language itself. The context is not just a source of input for the receiving learner, but rather, it provides the condition for interaction for active meaning-making… participants relate to each other and the tools and resources in context to generate language use and reflection on language use. (Liddicot & Scarino, 2014, p. 39-40)

In teaching and learning a language, considering semiotic resources such as color, layout, and typography will enhance the understanding and the quality of the messages. From an instructional perspective, I have found that selecting or designing pedagogical materials that involve different modes of communication strategically facilitates students' understanding and engagement. The use of multimodal texts enriches the expressive possibilities of students as I have realized in my language classes. Some of my students have indicated that besides allowing them to express their ideas, semiotic resources such as colors, types of fonts, images, and space distribution have enabled them to convey their emotions and attitudes at another level that is not necessarily linguistic. One example of this is the creation of digital posters on Glogster. Students have shown that through the use of certain colors and music they have constructed or contributed to the overall tone of the message. Students have observed that messages in social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter are multimodal and that multimodal awareness is needed to make meaning of these types of texts. Providing students with tools to understand multimodal texts will not only help them become better meaning makers but also will expand the teachers' possibilities to choose pedagogical materials from different sources.

Perhaps the most challenging task in engaging students in understanding communication from a multimodal perspective is establishing connections across the semiotic resources that interplay in a text. As I have indicated above, the best way to accomplish this is by drawing on the metafunctions proposed by Halliday (1978). Halliday's framework is illuminating because it allows learners to realize that in all acts of communication people make meaning about their world experiences (ideational metafunction), about themselves (interpersonal metafunction), and about the acts of communication themselves (textual metafunction). One important component in language learning is reflexivity (Clark & Dervin, 2014) and guiding students to think of these metafunctions will not only contribute to their language development and to understand the working of communication and meaning making, but also enhance their critical thinking. Without the need to rely in the terminology introduced by Halliday, students can be made aware that texts always represent our experiences in the world and that the semiotic resources we chose to use are instrumental in conveying our meanings or worldviews. Students should be aware that texts often convey several meanings as it was exemplified in the analysis of the SG. They could be guided in exploring how the designer of a text represents her/himself and how the readership is represented. In a second/foreign language class where most pedagogical materials come from Anglo-centered perspectives, interesting discussion could arise as students discuss the cultural values, stereotypes or beliefs behind, for example, the ways Americans or the British plan a party compared to the cultural values and behaviors attached to such practices in other communities such as the Colombian one. Textbook illustrations, dialogues, and exercises as multimodal ensembles provide insight into the assumed identities of authors and the ways they position potential users of textbooks. Asking students to think of these issues will encourage critical thinking and promote intercultural awareness. In connection to the role of textbooks in ELT, Álvarez (2014) in reviewing research conducted about the role of culture in Colombian publications found that "textbook contents contribute to the spread of stereotypes associated with the members of minority and dominant groups (aka British or North American cultures), their lifestyles, and social roles which might have a negative effect on students' perception of their own and the target culture" (p. 4-5).

One way to engage students in finding textual meaning is by asking them to identify the elements that characterize texts. The examination of the SG showed that its textual features corresponded to a college textbook. Students can be involved in several activities to raise awareness on aspects of genre and how the features of a text build coherence and cohesion. As an illustration, I have provided my students with lyrics of songs and asked them to identify the type of text. Although some of them recognize elements from the genre poetry (stanzas and many times rhyme), they identify uses of language (colloquialisms, contractions, nonstandard uses of language and ungrammatical forms) that lead them to consider the text as example of a song. This activity can be extended if the lyrics of a song are contrasted with the musical composition or music video in which students can be asked to further identify visual and sound elements of musical genres such as rock, ballads, rap, and pop. Introducing songs, comics, or advertisement as sources for language learning set the context to help students understand the textual metafunction. By doing this, students will not only understand that internal devices of the language work to establish cohesion and coherence, but also that in multimodal texts color, typography, images, layout, and language interact in ways that create coherent compositions. Broadly speaking, this section has shown that in language teaching, materials play a paramount role since it is about them and from them that most meaning making work is carried out. The digital age has brought about a myriad of options in the design of multimodal materials. In the next section, I focus on digital materials common in language learning websites (see Álvarez, 2015)

Language Learning Websites as Digital Multimodal Environments

The advent of the Internet and the World Wide Web (WWW) marked a turning point in the area of Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL). By featuring tools such as audio recording and playback, video, interactive activities, error checking, and voice recognition, language-learning software interconnected diverse semiotic resources to enhanced learners' opportunities to develop language skills. The CALL software industry that had traditionally gravitated around the design of CD-ROMs, usually aimed for individual use, had to adapt to the logics and technical requirements of the WWW. While some of the software programs developed in CD-ROM format moved online or developed hybrid versions, the WWW gave rise to a new type of educational software commonly known as language learning websites (LLW).

A language learning website is an online environment characterized by offering language learners practice on some or all of the language skills. Materials may consist of grammar explanations, grammar or vocabulary exercises, flashcards, videos, and audio materials. Some of these sites are sometimes organized in the form of an online course with a sequential order of lessons (e.g., Livemocha, Busuu), while some others offer a wealth of activities and materials without any particular implied sequence of development (e.g., Englishclub.com). From a commercial standpoint, these websites are usually available for free to any user on the web, although some might have a premium registration to access certain contents. From a technical perspective, there are three kinds of LLWs available on the web. The first group involves sites whose interfaces correspond to Web 1.0 (mostly text centered pages with little multimedia use); the second one is a hybrid between Web 1.0 and 2.0. Within this group users can locate sites such as LEO.com, a site that seems to have been adding elements from Web 2.0 to its initial design that was built on the Web 1.0 infrastructure. To the third group belong sites such as Livemocha and Busuu, which make use of the affordances of Web 2.0 (O'Reilly, 2005; Warschauer & Grimes, 2007), involving synchronous text and video chat and social networking.

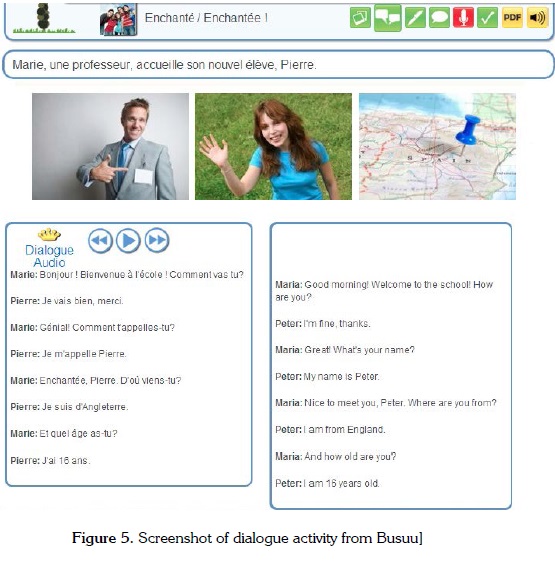

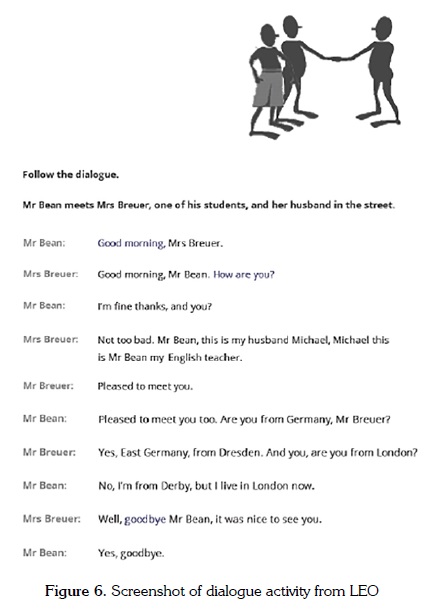

I have chosen one example of a LLW built under the technological affordances of Web 2.0 in order to contrast it with a website that was designed based on the logic of Web 1.0. The first website, Busuu (see Figure 5), was created in 2008 and provides users the opportunity to learn or practice up to 12 languages, including English, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Russian. It allows learners to use most of its features for free; however, it charges a monthly fee to become a premium member and gain access to additional functionalities. Busuu offers a self-paced language program enhanced by interactive multimedia content and social networking environment. Based on the concept of community, it provides tools for on-line communication such as audio and video chat and voice recording. The second website, Learn English Online (LEO, Figure 6), was created in 1999. It provides a list of English lessons that can be used for free to practice different language skills through audio, video, grammar exercises, stories and poetry. It makes links available to other educational materials and provides a forum for users to engage in interaction with a tutor that checks their written compositions and offers extra vocabulary and grammar explanations.

Conducting a detailed analysis of these websites is beyond the scope of this paper. For illustration purposes, I have chosen the topic (introductions) and one activity (dialogue) from both websites (Figures 5 and 6). Often times when I ask teachers which of these two dialogues they would use if they were to teach the topic of introductions, the most common answer is the dialogue presented on Busuu. At first sight, Busuu's interface seems to be more pleasing to the eye, a result that arises from an effective combination of modes of communication (Figure 5). The semiotic resources that compose this page include written language, audio, boldfaced text, color, image, spatial distribution (specific layout) and hyperlinks. The activity is introduced through a general title at the top "Enchante/ Enchantée," preceded by a photograph that provides context to the topic of the unit (meeting people). This is followed by a blue box that introduces the communicative context of the dialogue that will be presented below: "Marie, une professeur, accueille son nouvel éléve, Pierre" (Marie, a teacher, welcomes his new pupil, Pierre). Below this communicative context appear three photographs that provide a visual complement. In a way, the pictures create intersemiotic coherence between the linguistic mode and the visual mode since they portray a man and a woman that by association would embody Marie and Pierre. The set of pictures also includes a photograph of a map that indicates the geographical context where the interaction is supposedly taking place. What follows below is the space for the dialogue, which is divided into two spaces framed by two boxes: the one on the left provides the transcript of the dialogue in the target language, while the box on the right provides the translation of the dialogue text in the preferred language of the learner. In this section, elements of the linguistic mode of communication (written language, spoken language, font, boldface) co-occur with other modes such as spatial distribution.

The pedagogical benefits of this interface are varied. First, all the elements of the semiotic design of this activity make the page aesthetically welcoming, tapping into the aesthetic sensitivities of users who would feel more attracted to colorful and illustrated learning materials. Second, the activity is pedagogically appropriate. The page makes available semiotic resources to scaffold students' learning by providing, first, visual cues that help embed language in communicative contexts and, second, interactive tools such as the dialogue audio and the translation tool. The activity aligns with communicative views of language teaching that point at the relevance of presenting language in functional and communicative contexts. By combining different modes of communication the interface provides comprehensible input which assures students' understanding of contents. Additionally, by providing the audio recording of the dialogue as well as its transcription and other resources of the website (not included in the screenshot) mainly a dictionary or access to other learners in the online community, the website promotes autonomous learning. Most importantly is the fact that multimodal texts such as the one examined above provide better opportunities for language learning as has been shown by Guichon and McLornan (2008) who concluded that language "comprehension improves when learners are exposed to a text in several modalities" (p. 85).

LEO offers a more traditional interface centered on the linguistic mode of communication, combined with other resources such as image, color, hyperlinks, and spatial distribution (Figure 6). Different from Busuu, the title "Naturally Speaking" does not serve to situate thematically the dialogue or a communicative function of language (meeting people, greetings). The image at the top, a clip art of people greeting each other, along with the introduction to the dialogue ("Mr Bean meets Mrs Breuer…") contextualizes the dialogue and the three characters in it: two males (Mr Bean and Michael) and a female Mrs. Breuer. It is interesting to observe that while Busuu draws on photographs to help create the communicative context of dialogues, LEO uses clip art. Research in the area of multimodality shows that photographs are thought to be reliable because they reproduce rather than represent reality; they evoke meanings that agree with naturalistic conventions (Baldry & Thibault, 2006; Kress & van Leeuwen, 1996; Machin, 2007; van Leeuwen, 2005). On the other hand, clip art is deemed often as visual opinions and less factual (van Leeuwen, 2005). Thus, the semiotic ensemble of Busuu represents in a more naturalistic way the target communicative situation (greetings, introductions) if compared to LEO's choice of semiotic resources. In turn, this naturalistic depiction of the context and speakers provides a more realistic learning experience since language manifests in real settings and with real people.

Different from Busuu, LEO does not provide a tool to play the audio of the dialogue and a translation tool. Instead, LEO provides access to audio through hyperlinks. In this dialogue three language units are hyperlinked: "Good morning" "How are you?" and "Good bye." After clicking on these links, users are directed to the bottom of the page where they can listen to these and other expressions. One explanation that helps understand LEO's semiotic design might lie in the fact that the website was constructed under the structural possibilities that the web 1.0 offered along with the dominant views of language learning of the time. Overall, LEO's way of introducing language appears less attractive and demands more navigational effort from learners.

By and large, this section suggests that the new generation of language learning websites through their usually complex multimodal ensembles offer users new ways to experience language learning. This short analytic exercise also indicates that in the new communication landscape of digital environments, the semiotic work is divided between both the content and the form in which the content is arranged to create the intended meanings. In closing, I will briefly discuss some ideas about how to make more visible the multimodal perspective in language classrooms.

Recommendations to Integrate the Multimodal Approach in Language Classes

One big step that we need to take as educators is to recognize that all elements that are included in a text or communicative act have meaning potential. From this point of departure, the work with students should focus on helping them understand how to interpret and design multimodal texts. These are some ideas on how to do that:

• Make students aware that all elements in a text help build meaning. As we have seen above, one way to do this is by examining the different modes of communication that compose texts. Engage students in reflecting about the possible intentions of elements (base units) within distinct modes of communication and text genres.

• Discuss the characteristics of genres such as textbooks, brochures, postcards, letters, chat scripts, articles from newspapers, websites, and video clips. Look at the patterns of genres (e.g. common structure of ads). All genres have structural patterns and identifying them will help comprehension and text design. This is especially relevant in language classrooms where different text genres are used to approach the target language.

• Design tasks that require students to create multimodal texts in connection to the various topics (e.g. family, daily routine, likes and dislikes) and communicative functions of the language curriculum. Guide students in the design of texts such as electronic posters, postcards, handouts, blogs, videos, and the like based on their skills and access to materials. It is always good to begin by asking students to find and analyze examples of successful texts within the genre they chose to focus on. During the design stage, guide students' work through questions such as: What modes of communication will be used in the design of the selected text? How can the combination of images, layout, color, typography etc. contribute to create a persuasive text? How do the elements of the text match the characteristics of the genre chosen? How are the messages in the text related to social and cultural aspects of the intended audience?

• Link student's learning styles to multimodal projects. Students have learning preferences (e.g. visual, auditory, spatial, tactile); usually those who are visual learners will opt for posters or videos. Be willing to encourage these choices but also invite students to explore and combine other learning styles and genres they are unfamiliar with.

• Design materials articulating modes of communication and genres that provide different sources of input to the topic or language function being studied. A language function such as 'talking about the past' could be addressed through multiple activities, including blogs in which students narrate through video, image, and written text what they did during their vacation period. It is important to consider that, although a combination of modes of communication can enhance comprehension and recall (Paivio, 1986, 2007), not all combinations of semiotic resources lead to sound pedagogical materials. An illustration of this is the studies of Mayer (2001) who shows that digital texts combining animation, written text, and audio produce cognitive stress and hinder comprehension.

• Finally, talk about plagiarism. Due to the availability and democratization of knowledge enacted by the social web, for students the primary source of materials in constructing multimodal texts is the Internet. Most multimodal designs your students will create will include bits and pieces of multiple prefabricated texts shared online. It is necessary that students be introduced to the rules fair use and proper attribution of online materials.

Conclusion

Gunther Kress (2003, 2010) as well as many other scholars (van Leeuwen, 2005; Jewitt, 2008, Bezemer & Kress, 2008; Machin, 2007) have shown that the multimodal approach enriches our understanding of communication, especially, in the current textual habits, which are highly mediated by digital technologies. Kress' reflection about communication inexorably leads us to reconceptualize language and its role in several areas of knowledge and social domains, including education. In particular, in the field of second/foreign language teaching and learning, the multimodal perspective has not gained theoretical and epistemological import. Although as can be seen from my exposition above, multimodality has a lot to say about material design and, in due course, its insights will have shaping effects in curriculum, learning and pedagogy (Jewitt, 2006).

It is my hope that this general introduction to the topic along with practical examples and some suggestions about how to integrate the multimodal perspective in language classes serves the purpose of making this approach more accessible. In my view, the greatest take-away lesson of this discussion is that all communication is multimodal and by ignoring some of the elements that constitute texts, we are missing important building blocks in the process of meaning making and meaning negotiation. I firmly believe that as meaning making and texts become more complex and sophisticated, language educators and educators in general are called to help students understand the new dynamics of text construction and text interpretation. After all, there is no dimension in the human sphere that is not mediated by language and interpretation.

Notes

2 These are nonverbal elements that part take in meaning making during interactional encounters. While proxemics refers to the spatial proximity between speakers, chronemics involves the role of time in interactive exchanges. Gesture and gaze account for the expressions conveyed through bodily action and the way speakers focus their attention through eye fixation, respectively. Spatial distribution comprises the arrangement of individuals or objects involved in a communicative situation.

3 Although I conducted the analysis following the steps in a linear way with a specific point of departure, figure 2 shows that the text provides different points of entry and possibly various manners of combining the four steps.

4 For pedagogical purposes, the analysis presented here will focus on general aspects of a multimodal analysis. For a more fine-grained and sophisticated analysis of a printed page see Baldry and Thibault (2006); Machin (2007), and Bateman (2008).

References

Álvarez, J. A. (2015). Language views on social networking sites for language learning: The case of Busuu. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1-17. doi=10.1080/09588221.2015.1069361.

Álvarez, J. A. (2014). Developing the intercultural perspective in foreign language teaching in Colombia: A review of six journals. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14(2), 1-19.

Baldry, A., & Thibault, P. J. (2006). Multimodal transcription and text analysis. Oakville, CT: Equinox Pub.

Bateman, J. A. (2008). Multimodality and genre: A foundation for the systematic analysis of multimodal documents. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Beetham, H., Mcgill, L., & Littlejohn, A. (2009). Thriving in the 21st century: Learning literacies for the digital age (LLiDA project). The Caledonian Academy, Glasgow Caledonian University: UK.

Bezemer, J., & Kress, G. (2008). Writing in multimodal texts: A social semiotic account of designs for learning. Written Communication, 25(2), 165-195.

Busuu.com Retrieved from http://www.busuu.com/.

Clark, J. B., & Dervin, F. (Eds). (2014). Reflexivity in language and intercultural education: Rethinking multilingualism and interculturality. New York/London: Routledge.

Cloonan, A. (2010). Multiliteracies, multimodality and teacher professional learning. Australia: Common Ground Publishing.

Cousins, C. (2013). Serif vs. Sans Serif Fonts: Is One Really Better Than the Other? Retrieved from http://designshack.net/articles/typography/serif-vs-sans-serif-fonts-is-one-really-better-than-the-other/.

Duff, P., & Talmy, S. (2011). Language socialization approaches to second language acquisition. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches to second language acquisition (pp. 95-116). London: Routledge.

Eggins, S. (2004). An introduction to systemic functional linguistics. New York: Continuum.

Gee, J. P. (2001). New times and new literacies: Themes for a changing world learning for the future. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Proceedings of the learning conference (pp. 1-20). Greece: Learning Conference & Common Ground.

Guichon, N., & McLornan, S. (2008). The effects of multimodality on L2 learners: Implications for CALL resource design. System, 36, 85–93.

Haley-Brown, J., Lee, J., & Rodriguez, C. (Eds.). (2011). A student's guide to first-year writing, 32nd ed. Plymouth: Hayden-McNeil Publishing. .

Halliday, M., & Hasan, R. (1986). Language, context and text: Aspects of language in a social-semiotic perspective. Geelong: Deakin University Press.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic. The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Hawisher, G., & Selfe, C. (2000). Conclusion: Inventing postmodern identities: Hybrid and transgressive literacy practices on the web. In G. Hawisher & C. Selfe (Eds.), Global Literacies and the World Wide Web (pp. 277-290). London: Routledge.

Hodge, R., & Kress, G. (1988). Social semiotics. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press in association with Basil Blackwell.

Jewitt, C. (2006). Technology, literacy and learning: A multimodal approach. London: Routledge.

Jewitt, C. (2008). Multimodality and literacy in school classrooms. Review of Research in Education, 32(1), 241–267. doi:10.3102/0091732X07310586.

Jewitt, C. (2009). An introduction to multimodality. In C. Jewitt (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis (pp. 14-27). Abingdon: Routledge.

Jewitt, C., & Kress, G. (2003). Introduction. In C. Jewitt & G. Kress (Eds.), Multimodal literacy (pp. 1-18). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Kalantzis, M., & Cope, B. (2008). Introduction: Initial development of the 'multiliteracies' concept. In S. May & N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education, Vol.1: Language policy and political issues in education (pp.195–211). New York: Springer Science+Business Media LLC.

Kress, G. (1997). Visual and verbal modes of representation in electronically mediated communication the potentials of new forms of texts. In I. Snyder (Ed.), Page to screen: Taking literacy into the electronic era (pp. 53-79). London: Routledge.

Kress, G. (2000). Multimodality: Challenges to thinking about language. TESOL Quaterly, 34(2), 337-340.

Kress, G. (2003). Literacy in the new media age. London: Routledge.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality a social semiotic approach to communication. London: Routledge Falmer.

Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.

Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse. London: Arnold.

Lankshear, C., Peters, M., & Knobel, M. (2002). Information, knowledge and learning: Some issues facing epistemology and education in a digital age. In M. Lea & K. Nicoll (Eds.), Distributed learning: Social and cultural approaches to practice (pp. 16-37). London: Routledge.

Learn English Online.com (LEO). Retrieved from http://www.learn-english-online.org/.

Machin, D. (2007). Introduction to multimodal analysis. London: Hodder Arnold.

Liddicoat, A., & Scarino, A. (2014). Second language acquisition, language learning, and language learning within an intercultural orientation. In A. Liddicoat & A. Scarino (Eds.), Intercultural language teaching and learning (p. 31-46). Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Mayer, R. E. (2001). Multimedia learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O'Reilly, T. (2005). What is Web 2.0. Design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. Retrieved from: http://oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html?page=5.

O'Halloran, K. L., & Smith, B. A. (2011). Multimodal studies. In K. L. O'Halloran & B. A. Smith (Eds.), Multimodal studies: Exploring issues and domains (pp. 1-13). New York: Routledge.

Paivio, A. (1986). Mental representations: A dual coding approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

Paivio, A. (2007). Mind and its evolution: A dual coding theoretical approach. Mahwah, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates.

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60–92.

van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing social semiotics. London: Routledge.

van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Towards a semiotics of typography. Information Design Journal+ Communication Design, 14(2), 139-155.

Warschauer, M. (2010). Digital literacy studies: Progress and prospects. In M. Baynham & M. Prinsloo (Eds.), The future of literacy studies (pp. 123-140). Houndmills, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Warschauer, M., & Grimes, D. (2007). Audience, authorship, and artifact: The emergent semiotics of Web 2.0. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 27, 1-23.

Waugh, L., Álvarez, J. A., Do, T. H., Michelson, K., & Thomas, M. (2013). Meaning in texts and contexts. In K. Allan (Ed.), Oxford handbook of the history of linguistics (pp. 613-634). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.