DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.3147Publicado:

2007-01-01Número:

No 9, (2007)Sección:

Artículos de InvestigaciónEFL chinese students and high stakes expository writing: a theme analysis

Palabras clave:

Textos Expositivos, Ingles como Lengua Extranjera, Estudiantes de Nacionalidad China, Lingüística Sistémica Funcional, Cohesión, Pedagogía de Géneros Literarios (es).Palabras clave:

Expository Texts, EFL, Chinese Students, Systemic Functional Linguistics, Cohesion, Genre-based Pedagogy (en).Descargas

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Research Article

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 2007-09-00 vol:9 nro:1 pág:99-125

EFL Chinese Students and High Stakes Expository Writing: A Theme Analysis

Qian Yang - J. Andrés Ramírez - Ruth Harman

Abstract

The expository essay in English is a key gatekeeping milestone as students seek to move from one level of schooling to the next (Schleppegrell, 2004). Using Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), this study analyzes a Chinese college student's expository essay written on a nationwide English examination in China. Two aspects of theme in the textual metafunction will be examined: theme markedness and theme progression (Eggins, 1994; Halliday, 1994). These components are further explored through a parallel analysis of an expository essay written by a North American freshman. This comparative theme analysis highlights areas in pedagogy that should be attended to if EFL students are to get more sophisticated control over important features of expository writing.

Key words: Expository Texts, EFL, Chinese Students, Systemic Functional Linguistics, Cohesion, Genre-based Pedagogy

Abstract

El ensayo expositivo en inglés es un paso importante para estudiantes que quieren avanzar en su nivel de estudios (Schleppegrell2004). El marco teórico asociado con la Lingüística Sistémica Funcional (SFL por sus siglas en inglés), es utilizado en este estudio para analizar el ensayo expositivo de un estudiante chino requerido para un examen de carácter nacional en China. Dos aspectos temáticos de la metafunción textual serán examinados: particularidad y progresión temática (Eggins, 1994; Halliday, 1994). Estos componentes son explorados mas profundamente a través de un análisis paralelo de un texto de las mismas características funcionales y de contenido escrito por un estudiante de primer año en una universidad de Estados Unidos. El análisis temático comparativo revela áreas pedagógicas que deberían tenerse en cuenta para que los estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera puedan tener un control más sofisticado de las características más importantes de textos expositivos.

Palabras Claves: Textos Expositivos, Ingles como Lengua Extranjera, Estudiantes de Nacionalidad China, Lingüística Sistémica Funcional, Cohesión, Pedagogía de Géneros Literarios.

Introduction

Chinese college students are expected to write expository essays on different types of English exams such as grade level final exams and the nationwide College English Test. Expository writing has become a necessary skill to advance in schooling and seek satisfactory job positions. Undoubtedly, instruction on expository writing plays an important part in the Chinese EFL field.

This study uses systemic functional linguistics (SFL) to analyze a Chinese college student's expository essay for a nationwide English examination. The study also compares the expository essay written by the Chinese college student to that written by an American freshman. This comparison is carried out in order to investigate linguistic differences in the way the students realize the expository genre in general and the theme of clauses in particular. Theme is an element of the textual metafunction, an important conceptualization for SFL, the framework for this study. With the textual metafunction as the focus, two aspects of theme will be examined: theme markedness and theme progression.

Differences and similarities in the texts are used to draw implications about areas of writing pedagogy that should be included to provide students with the tools to gain better control over the features of expository writing. Based on our findings about the different meaning patterns in the two expository essays and on research about the general register features of exposition, explicit instruction on writing within an SFL genre-based pedagogy is suggested.

As mentioned above, systemic functional linguistics is a major theoretical framework used in this study. Genre-based pedagogy, understood as an adaptation of SFL also plays a central role: this type of explicit linguistic instruction was adapted from SLF by the Sydney School of Genre in the 1980s (i.e., Christie & Martin, 2000; Macken & Rothery, 1991; J. Martin, Christie, & Rothery, 1987; J. Martin & Rothery, 1986a, 1986b) and used by the Australian linguists to provide explicit genre instruction to culturally and linguistically diverse students in Western Australia.

Influenced by Bernstein (1990), and Halliday’s research in the 1960s on different socio economic discursive practices, the Sydney genre theorists believed that students’ primary discourses (Gee, 1996), on entry to the school system, affected how they succeeded in the new environment: the larger the gap between the secondary discourses of school and their primary discourses at home, the lower the sets of expectations, literacy trajectories and accolades for the student (Hasan & Williams, 1996; J. R. Martin, 1989; Rothery, 1996). Martin (1989) and Rothery (1996) saw an SFL based explicit pedagogy as a systematic way of addressing these inequities. In recent years it has been adopted in ESL and EFL contexts (i.e., Gibbons, 2006; Paltridge, 2001) but it still lacks adequate recognition and has only recently attracted attention in the US (Schleppegrell, 2004; Schleppegrell & Colombi, 2002).

In this article, SFL was used to analyze the student texts and also to reflect on the importance of using a SLF genre based pedagogy in ESL writing instruction. Both SFL and genre theory emphasize that writers organize and structure their texts in relation to their social purpose and cultural context. In this research, how the different contexts of culture and ideology influence two students’ different patterns of the written argument is also analyzed.

Macro Context

It is irrefutable that United States with its world’s largest economy, “its intellectual industries, scientific and military systems, mass media and publishing exert substantial control over dominant modes of representation and communication” (Luke & Luke, 2000). These dominant modes that Luke & Luke (2000) talk about are mainly discursive: in other words, they are mediated by language as a semiotic system . In current times, they are mediated by the English language. In fact, English has grown to the status of a global language in recent decades.

English has become the lingua franca for economic and scientific exchange and indeed has led to the emergence of new cultural patterns (Warschauer, 2000). Most international organizations in the world use English; most academic journals (about 90%) are published in English. In other words, many of the cultural, economic and political transactions in the global community are done in English. Crystal (1997, p. 60) estimates that more than one third of the world population speaks English. Of these, an estimate of 235 million people have learned English as a Second/ Foreign language. In fact, the influence of English is so persistent that in the world today, there are more people who speak English as a second language than native speakers of English (Crystal, 1997).

Although China is one of the strongest economies in the world, currently the Chinese language exerts far less international influence than the English language. Instead, as a strategy to stay current and competitive, the Chinese government has to emphasize English language training. Wu Yongke, director-general of the training department of China’s Economic and Trade Commission (SETC) recently declared that “Since China’s WTO entry, competition for talent will intensify, and the Chinese government and enterprises will emphasize vocational training, particularly English language training” (People’s Daily, 2002).

One of the areas of English language training that has received special attention in China has been the expository or argumentative essay. This text type is a genre that requires writers to advance a point of view or thesis and support it with arguments (Martin, 1989; Schleppegrell, 2004). The expository essay is a current key gatekeeping milestone for students in China as students seek to move from one level of schooling to the next. In this article, based on genre theory scholars (i.e., Christie & Martin, 2000; Hasan & Williams, 1996; Knapp & Watkins, 2005; Paltridge, 2001) who have successfully used genre theory in special needs classrooms as well as in regular classrooms, we argue that explicit instruction to the linguistic and structural features of the expository essay will not only benefit Chinese students academic writing but will be beneficial to students in other EFL/ESL contexts.

Theoretical Framework

SFL is a broad social semiotic approach to language, originally articulated by Halliday in the 1960s. It is concerned primarily with a dynamic set of choices made available to speakers of a language to communicate in different social contexts and for particular social purposes (Halliday, 1994). Any text simultaneously makes these three kinds of meaning: the ideational, the interpersonal and the textual. The simultaneous presence of each of these meanings in any text is necessary if anyone is to make sense of each other and the world around them.

How does a text necessarily build three kinds of meanings? First, a text is always about something (Ideational meaning). Ideational meanings construe our experience of the world (Butt, Lukin, & Matthiessen, 2004; Eggins, 1994; Halliday, 1994). Second, it addresses the audience in certain ways - as experts or novices, as related to the producer of the text or as strangers (Interpersonal meaning). Interpersonal resources enact our social roles and power relations.

In most Chinese classrooms, for example, teachers tend to use the declarative mood almost all the time while students mostly use the interrogative mood. Social roles and power relations associated with teachers and students are expressed this way as the expectation for teachers in most eastern countries is to pass on knowledge while students receive it and ask questions to which a response may enhance their understanding.

Third, a text expresses textual meaning (discourse) because a text always builds on what has been said before and what is being said through texture. What this means is that textual resources organize the other two kinds of meanings (ideational and interpersonal) as a ‘flow of information that is possible for listeners and readers to process’ (Butt et al., 2004).This third meaning, while expressing a semantic meaning (textual) also relates more explicitly that the other meanings to the generic structure of the text. For example, the system of THEME and RHEME organizes meaning on the clause level but also on a whole text level. Fernando Trujillo explains the system as follows:

The speaker/writer decides where to start the sentence and the beginning of each sentence is its theme. The rest of the sentence tells the hearer/reader something about the theme. That “rest of the sentence” is called rheme. The theme is the framework or the point of departure of the message. The rheme is what the addresser wants to convey about the theme. . . The addresser uses theme and rheme to highlight a piece of information in the sentence. . . Theme and rheme are also used to organize the information in the text. Frequently, the rheme in one sentence becomes the theme in a following sentence. This phenomenon is called communicative dynamism. Furthermore, there is also a thematic organization of the paragraph. In English the first sentence of a paragraph is also the theme of that paragraph (topic sentence), whereas the following sentences have a rhematic value (supporting sentences), which develop the idea proposed by the theme by means of examples, counterarguments, etc. (Trujillo, NA).

Thus, the textual meaning organizes the other two kinds of meaning through the system of theme and in doing so expresses both semantic and discursive meaning. The two aspects of theme realization that are related to the present research are: theme markedness and theme progression. Theme, as defined by SFL linguists, is the point of departure in a clause and rheme is the rest of the clause. For example, in the following clause written by the American student for this study, she writes: Dishonesty takes many forms in today’s society. The first word is an unmarked experiential theme because the writer has conflated the subject of the clause with its point of departure. However, often writers may use a variety of other ‘marked’ themes to start a clause such as a circumstance or an interpersonal comment

For example, the writer in the example above could have started the clause with an “unfortunately” or “In today’s society.” In SLF we analyze this variety in starting a clause through the concept of theme markedness. When the writer opts for a marked choice, they “signal that all things are not equal, that something in the text requires an atypical meaning to be made.” (Eggins cited in Thomson, 2005). Indeed, thematic choice can reflect the diversity of the writer's resources. A developing writer with more limited resources may be restricted to less marked options (Thomson, 2005). In this article, we analyze all themes that do not conflate the subject and theme in the clause as ‘marked’ themes.

Theme progression is another SLF concept that is used to track the relationships between the theme of a clause and the themes and rhemes of subsequent clauses. Two predominant patterns of theme progression include “linear progression” -theme of clause derived from rheme of earlier clause and “iterative progression” -repetition or co-reference of theme in subsequent clauses (Thomson, 2005). These are two ways in which the system of theme/ rheme is organized. For example, in the following clauses written by the Chinese student, she uses linear progression to link the clauses.

Besides, to behave ourselves is to behave in an honest way. (1)

And what’s more, being honest is the essential step towards spiritual civilization. (2)

The previous example shows the new information or rheme being picked up as given information or theme in the subsequent clause. This zig-zag pattern is used to achieve “cohesion in the text by building on newly introduced information” (Eggins, 1994 p. 304).

An illustration of iterative progression is also relevant at this point. As can be seen in the following clauses, Diana uses iterative progression to highlight the importance of the theme in the introductory clause (themes are in bold).

Someone who steals has far bigger motives than to escape the wrath of an upset parent. He may need money, or (he) is looking for attention from friends who egg him on, or perhaps he just steals for the adrenaline rush it affords him.

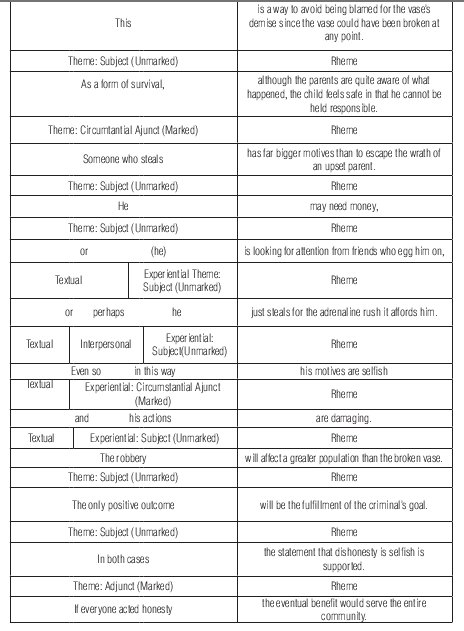

Unlike the previous example, Diana underscores the first theme in the paragraph “Someone who steals” by repeating it through the pronoun “he” in the three subsequent clauses. The following diagrams (adapted from Eggins 1994) graphically represent the two kinds of thematic progression referenced here.

In providing students with explicit instruction on complex linguistic features such as theme markedness and theme progression, SLF linguists worldwide but especially in Australia have been adapting SFL for K-12 and ESL settings over the past three decades (J. Martin & Rothery, 1986a; Schleppegrell, 2004). These theorists see the importance of teaching both the linguistic range of choices of different academic registers and also the type of structure or ‘stages’ that a genre tends to have to communicate for specific social purposes and contexts of use (Herrington & Moran, 2005). Christie (1999) claims that the study of genres is useful in teaching ESL/EFL students for the following reasons: 1. They offer a principled way to identify and focus upon different types of English texts, providing a framework in which to learn features of grammar and discourse. 2. They offer students a sense of the generic models that are regularly revisited in an English-speaking culture, illuminating ways in which they are adapted or accommodated in long bodies of text in which several distinct genres may be found. 3. They offer the capacity for initiating students into ways of making meaning that are valued in English-speaking communities (Christie, 1999).

Methodology

In this study the researchers compared examples of expository writing written by a Chinese student and a North American freshman to explore different patterns of meaning in both texts and possible areas for the ESL student to develop. Such explorations can be a useful basis for planning writing instruction programs.

The Chinese student's essay entitled “It Pays to Be Honest” was written for the Chinese College English Test which took place in Jan, 2003. It was top rated; as a result, it was included in a book about writing strategies as a good writing sample. The Chinese College English Test has been given twice a year since 1987 and has taken such an authoritative position that the scores of the exam are treated as equal with that of TOEFL and IELTS by many Chinese institutions and companies when they interview prospective employees.

The writing part of the test is evaluated by Chinese experienced college English teachers on a 15-point scale. According to the scale description, the compositions are given 14 points or over if they should meet the following standards: 1) The content is to the point. 2) Ideas are expressed clearly and cohesion and coherence should be achieved. 3) Moderate diversity of sentence patterns is required. 4) Only minor language errors are allowed.

For comparative purposes, the researchers also asked an American freshman to write an essay with the same prompt within the same period of time: 30 minutes. Diana Chase (a pseudonym), an 18 year-old freshman in a history major at University of Massachusetts-Amherst was brought up in a Euro American middle-class family. Diana was told her essay would be compared and analyzed in the same way than an essay written by a Chinese college student.

The directions both students followed to write the expository essay allowed them 30 minutes to write a composition on the topic: “It Pays to Be Honest.” They were directed to write at least 150 words following two ideas:

- Dishonest conducts exist everywhere in the world today, and

- People should behave honestly as it is beneficial to others and the honest person as well.

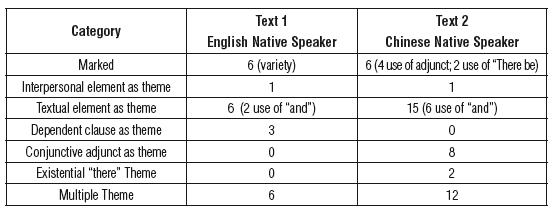

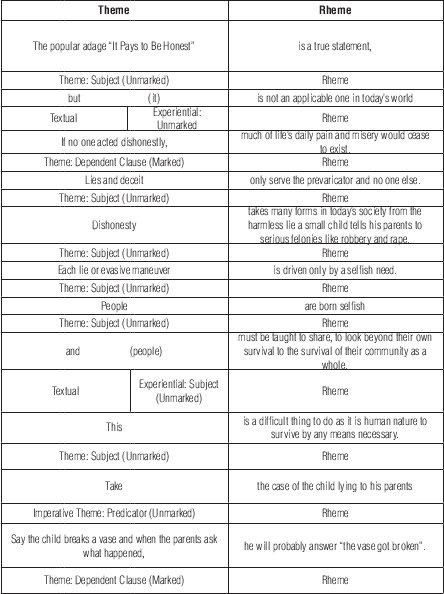

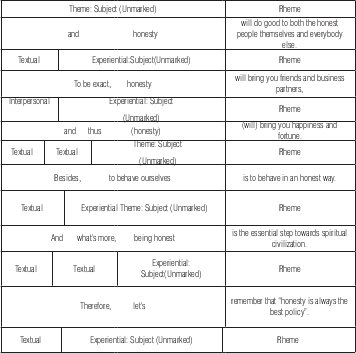

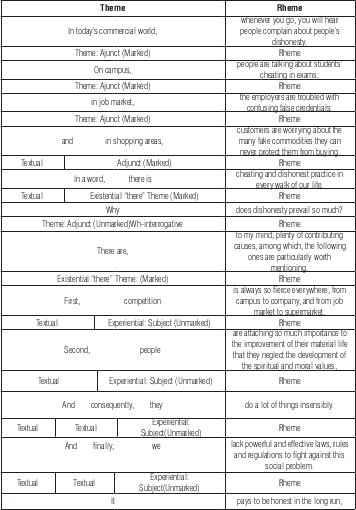

The entire texts the students wrote as well as a detailed analysis of Theme/ Rheme and theme progression can be found in Appendix I and II. A table summarizing the theme / rheme analysis in both texts is reproduced below.

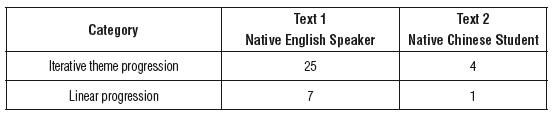

As table I shows, both texts make use of six marked themes. The closer examination, however, discloses a major difference: in Diana’s essay, among the six marked themes, there are three dependent clauses, two circumstantial adjuncts and one adjunct, while the Chinese student uses existential “there be” theme (two uses) and adjunct (four uses). Therefore, it’s safe to say the markedness in Diana’s essay shows greater variety and complexity. On the other hand, the Chinese student prefers to use textual element as theme, among which, “and” is used 6 times. Additionally, two textual themes emerge simultaneously in the Chinese student’s essay in four clauses. The table of summary of theme progression in both texts (see Table II) also indicates that the Chinese student uses much fewer cohesive devices. It is evident that the Chinese student depends mainly on more obvious and emergent organizational strategies. Detailed expansions of this last point will be addressed in the findings section.

Findings

Markedness

The close examination and comparison of the two essays reveal how the writers in different cultural contexts use theme markedness as a resource for cohesion. The findings are summarized as follows:

An analysis of the first paragraph of two essays shows that the writers choose to place circumstantial elements describing location of dishonest practices in different parts of the clauses. In the Chinese student’s essay, circumstantial elements of this kind either stay at the beginning of clauses as marked themes or appear at the end of existential clause (there be). Focus elements in text excerpts are italicized.

- In today’s commercial world, whenever you go, you will hear people complain about people’s dishonesty. On campus, people are talking about students’ cheating in exams; in job market, the employers are troubled with confusing false credentials; and in shopping areas, customers are worrying about the many fake commodities they can never protect them from buying. In a word, there is cheating and dishonest practice in every walk of our life. Contrary to this, Diana, the American student, positions these circumstantial elements within the rheme, as shown in the following two examples:

- The popular adage “It Pays to Be Honest” is a true statement, but (it is) not an applicable one in today’s world.

- Dishonesty takes many forms in today’s society from the harmless lie a small child tells his parents to serious felonies like robbery and rape. The different treatment of theme/rheme suggests a different understanding of how and where to provide new information. The Chinese student does not use rheme as in the most conventional way in English, that is, as the place to provide new information to state or illustrate what is described in the theme.

The themes after the circumstantial elements, namely, you, people, employers, customers, are very general and thus anything that can be said about them will necessarily be not only general but also abstract as it is the case here. More importantly, the Chinese student’s repeated use of circumstantial elements as marked themes limits her ability to use linear progression as another cohesive strategy. Because Diana on the other hand, tends to allocate circumstantial elements to the rheme, her text shows a much richer variety in theme progression and more subtle ways of signaling cohesion.

In addition, contrary to the Chinese student’s use of general themes, the themes in Diana’s essay are specific, very related to the topic, and allow for new information to be said about them in the rheme. In the above examples (2 and 3) Diana uses the themes “The Popular adage “it pays to be honest” and “Dishonesty” as the starting point of her argument and then goes on to state the non-applicability of the adage and the many forms dishonesty takes in today’s world (harmless lies, serious felonies). This new and specific information about the adage and dishonesty is all located in the rheme.

A different but related point deals with the lexical chains students used and/or have available to construct texts. Both the Chinese student and the American student repeatedly use “honesty” and “dishonesty” or similar lexical items as themes to give prominence to the topic “It Pays to Be Honest”. Diana in her text uses the following lexical chains related to the idea of honesty : The popular adage “It Pays to Be Honest” ; If no one acted dishonestly; Lies and deceit; Dishonesty; Each lie or evasive maneuver; and his actions; The robbery; If everyone acted honesty; The one person who behaves altruistically; Honesty. The Chinese student uses such themes as honesty (three uses); to behave ourselves, and being honest. This close examination of the theme suggests that the Chinese student’s lexical chains and structural patterns would benefit from explicit instruction to improve its richness and variety.

The analysis of themes also shows that the Chinese student reflects on honesty as a big social problem whereas the American student also does so but also pays specific attention to cases that illustrate them. In Diana’s essay, apart from “people” which appears once as theme, the following specific expressions appear as themes too: each lie or evasive maneuver; say the child breaks a vase and when the parents ask what happened; someone who steals; his actions; The robbery. While in the Chinese student’s essay, people; they; we (all of them refer generally) as well as in today’s commercial world; on campus; in job market are used as themes.

Explicit scaffolding in developing an array of choices in terms of theme markedness and lexical chaining will clearly be beneficial for students in ESL/ EFL contexts.

Thematic Progression

As mentioned earlier, writers use linear and iterative thematic progression. In what follows, we will use representative examples from the texts to illustrate these ways to give coherence to the text and build arguments. The second paragraph fro Diana’s writing provides another good example of linear progression.

(4) Dishonesty takes many forms in today’s society from the harmless lie a small child tells his parents to serious felonies like robbery and rape. Each lie or evasive maneuver is driven only by a selfish need. People are born selfish and (people) must be taught to share, to look beyond their own survival to the survival of their community as a whole. This is a difficult thing to do as it is 3human nature to survive by any means necessary.

As can be seen, Diana picked up information from the rheme of the first clause “from the harmless lie a small child tells his parents to serious felonies like robbery and rape”, and uses it as the point of departure for the next clause. The same pattern also appears in the last clause. In this way, she creates a cohesive link that moves the argument forward and makes the whole paragraph a cohesive unit.

Conversely, the essay written by the Chinese student does not seem to consistently employ the strategy of linear progression as a textual organizational tool. This use just appears once in the last paragraph. Recall that this fragment was analyzed previously.

(5) Besides, to behave ourselves is to behave in an honest way. And what’s more, being honest is the essential step towards spiritual civilization. Thematic progression is not apparent in most excerpts. As can be seen in the following:

(6) First, competition is always so fierce everywhere, from campus to company, and from job market to supermarket. Second, people are attaching so much importance to the improvement of their material life that they neglect the development of the spiritual and moral values, and consequently, they do a lot of things insensibly. And finally, we lack powerful and effective laws, rules and regulations to fight against this social problem.

Rather than cohering here text through the use of linear progression, the Chinese student seems to favor more emergent modes of textual organization such as conjunctive adverbs that are frequently overused by EFL/ESL students (Schleppegrell, 2004). This is evidenced in how often the student uses textual thematic choices (first, second, finally) that serve a good organizational purpose but that do not use the rheme in the previous clause as its starting point. The results are often themes (i.e., competition, people, and we) without apparent textual cohesion and linear progression as they do not draw on the rheme of a previous clause for the theme of the next clause. Before analyzing the important role that clause embedding plays in constructing logical and more elaborated arguments, a Table summarizing the thematic progression in both texts follows. This summary further gives evidence of the different use of the strategy of linear progression for building up arguments.

Another important aspect of cohesion is clause combining. Although within the limits of this article we cannot provide a thorough analysis of this cohesive device, we thought it would be useful to signal a few differences in the ways the writers develop this strategy in the two texts. We already implied in the discussion about thematic progression that a tightly constructed essay requires clause structure that enables the writer to present ideas that are logically linked in obvious ways. Such a style draws on embedded clauses and elaborated noun phrases (Eggins, 1994; Halliday, 1994).

The concluding paragraph of Diana’s essay shows the above strategy by using embedded clauses:

(7) In both cases the statement that dishonesty is selfish is supported. If everyone acted honesty the eventual benefit would serve the entire community. The one person who behaves altruistically is not directly benefited by his actions until someone else decides to sacrifice for the common good as well. Honesty is only beneficial to everyone as a whole if all selfish motives are left behind.

Diana uses embedded clauses to describe “dishonesty”, “honesty”, a person who behaves altruistically, and under which circumstances is history beneficial. As a whole unit, the concluding paragraph echoes the introductory paragraph, making her thesis “honesty is only beneficial to everyone as a whole if all selfish motives are left behind” very clear.

The Chinese student concludes the essay the following way:

(8) It pays to be honest in the long run, and honesty will do good to both the honest people themselves and everybody else. To be exact, honesty will bring you friends and business partners, and thus bring you happiness and fortune. Besides, to behave ourselves is to behave in an honest way. And what’s more, being honest is the essential step towards spiritual civilization. Therefore, let’s remember that “honesty is always the best policy”. To reiterate a point already made with excerpt 6 above, both examples 6 and 8 clearly suggest that instead of using theme/rheme structure as an organizational tool, and using the embedded clauses as clause-combining strategy, the Chinese student prefers to use conjunctive adjuncts and conjunctions (e.g. first, second, and finally; besides, what’s more, therefore, and,) to chain clauses, creating an organizational structure that is more emergent.

Implications

In educational applications of SFL, genres are key organizing principle for syllabi, and for teaching grammar. Genres are categorized according to the distinct ways in which texts begin, develop, and conclude, in order to fulfill their social purpose. Texts are always ‘packed’ in genres, but genres are structured in specific ways not because they should be so, but because all texts are embedded historically in a network of power relations in particular institutional sites and particular fields. As such, texts are always a ‘social strategy’ (Luke, 1996).

The macro structure of the expository essay is a structure of foreshadowing, arguing, and summing up. Through the expository genre, students present a point of view and support it with examples and evidence. More specifically speaking, students need to be able to effectively introduce a topic, state a position or thesis related to the topic, incorporate or acknowledge the writing of others, and link ideas through text transitions. They need to make generalizations that draw from their own experience and that of others. Judgments need to be justified with concrete evidence and examples as they are expected to adopt an authoritative stance, using a whole array of discursive strategies to present themselves as detached and knowledgeable (Schleppegrell, 2004).

As the Chinese student's expository essay shows, he/she overrelies on conjunctions and conjunctive adjuncts for clause linkages and thus limits his/ her opportunity to recur to strategies such as thematic progression reviewed here. Teachers can give students explicit instruction about the strategies for producing denser, more integrated texts through condensation of information in the nominal groups. The specific strategies include embedded clauses, elaborated noun phrases, nominalization, among others. These strategies are not to be taught on isolation or as simple skill training. They need to be part of a sustained effort to encourage and facilitate students’ use of their own social and political purposes in the texts they read and write . Such is a project of “reading the word and reading the world” (Freire & Macedo, 1987) but with an understanding of language as a system of choices functionally developed to satisfy our needs in society (Derewianka, 2000).

While this article is a research report and does not explore specifically the way these and other strategies are to be taught, readers interested in learning more about how to teach and promote academic literacy for different student populations may find the resources provided very useful (refer to appendix 3). All of these resources will support, among other things explicit instruction on language demands and structural features of genres. Thus, it is reasonable to find some strategies to teaching EFL/ESL students theme markedness, theme progression, and clause-combining strategies.

In addition to these important issues, we further highlight the importance of having open discussions about different appropriate cultural ways of constructing meaning and making these discussion an integral part of a genrebased pedagogy. That is, differences in constructing meanings, such the ones evidenced in the students’ texts we analyzed may be explained both in terms of the ‘pedagogic repertoire’ particular to the student and local available pedagogic “thought collectives” (Ramanathan, 2002) but also in terms of the ‘pedagogic reservoir’ particular to the culture .

Thus, in addition to targeting control over ideational, interpersonal, and textual resources to realize appropriate genres, learners should also be conscious about how different cultures and ideologies expect and value writing structures differently. Social practices of this type should be also explicitly taught and not left for students to figure out on their own. Because of its focus on the social construction of texts, that is, its attention to “textual organization arising out of particular social configurations or the particular relationships of the participants in an interaction”(The New London Group, 2000), genrebased pedagogy could guide ESL/EFL learners to familiarize themselves with different cultural ‘available designs’ so that they can be proficient in making meanings valued in English-speaking communities while valuing and relying on the ‘funds of knowledge’ (Moll, 1990) closely related and valued in their own culture.

As Mackinnon and Manathunga (2003) contend: “writing structures vary in different cultures. In many Asian cultures, the expected writing structure is like an inverted triangle where you start with broad picture and then move to specifics. In western academic writing, the expected writing structure is like a diamond shape where you start with specifics, broaden out, and then narrow in for the conclusion.” (Mackinnon & Manathunga, 2003). Dominant cultural patterns undoubtedly influence the way individual students construct their texts, but these dominance should be available in addition and not instead students’ own cultural modes of representation.

We hope that the specific differences in theme markedness, thematic progression, and clause combining detailed in this article paired up with the brief insights on cultural awareness just provided may shed a light into some of the choices the Chinese student favored when writing her essay in specific, and the way writing instruction is conducted in other related contexts in general.

Conclusion

The textual metafunction analysis of the two essays has revealed important differences in the students’ degree of control over the textual resources of theme and rheme, thematic progression, and lexical complexity. As previously stated, explicit instruction of genres and the specific language they trigger has proven effective with English language learners, especially those who are culturally and linguistically diverse. Our analysis suggests that even essays that are depicted as meeting the criteria of the Chinese raters could benefit enormously from explicit instruction on the features of the expository genre Under this rationale, genre-based pedagogy could be integrated in future writing instruction in Chinese college EFL teaching.

In addition to the textual elements, attention to textual social practices and how they are valued differently in a culture should be considered in instruction on academic writing. Contemporary genre theory as described here views genre as texts with conventionalized features as linked to recurring social purposes and contexts of use (Herrington & Moran, 2005). The above analysis suggests that the structuring of the essays in question may be related to the complex interplay of broad cultural differences and individual academic experiences. More research in this area is much needed.

Further Research

Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) focuses its inquiry on questions of power, ideology and hegemony through a recursive exploration of text and context (e.g., local, institutional and societal domains) . The present research focused on the local dimension and while it attempted to make some connections to social practices by making reference to the different contexts of culture and ideology and their influence in two students’ patterning of written arguments, much more could have been done in this area. Attention to these matters as they reflect reliance on other discourses and other cultural ways to realize genres could be an area for fruitful research.

References

Bernstein, B. (1990). The structuring of Pedagogic Discourse. London: Routledge.

Bernstein, B. B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control, and identity : theory, research, critique (Rev. ed.). Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Butt, D., Lukin, A., & Matthiessen, C. (2004). Grammar – the first covert operation of war. Discourse & Society,, 15(2-3), 267-290.

Christie, F. (1999). Pedagogy and the shaping of consciousness : linguistic and social processes. London ; New York: Cassell.

Christie, F., & Martin, J. R. (2000). Genre and institutions : social processes in the workplace and school. London ; New York: Continuum.

Crystal, D. (1997). English as a global language. Cambridge, U.K. ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Derewianka, B. (2000). Exploring how texts work. Sydney: Primary English Teaching Association.

Eggins, S. (1994). An introduction to systemic functional linguistics. London: Pinter Publishers.

Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy : reading the word & the world. South Hadley, Mass.: Bergin & Garvey Publishers.

Gee, J. P. (1996). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses. London, Briston, PA . Taylor & Francis.

Gibbons, P. (2006). Bridging discourses in the ESL classroom : students, teachers and researchers. London ; New York: Continuum.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1994). An Introduction to Functional Grammar (2 ed.). New York: Routledge.

Hasan, R., & Williams, G. (1996). Literacy in society. London ; New York: Longman.

Herrington, A., & Moran, C. (2005). The Idea of Genre in Theory and Practice: An Overview of the Work in Genre in the Fields of Composition and Rhetoric and New Genre Studies. In A. Herrington & C. Moran (Eds.), Genre across the curriculum. Logan: Utah State University Press.

Knapp, P., & Watkins, M. (2005). Genre, Text, Grammar: Technologies for Teaching and Assessing Writing. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

Luke, A. (1996). Genres of Power? Literacy Education and the Production of Capital. In R. Hasan & G. Williams (Eds.), Applied linguistics and language study. (pp. xxi, 431). London ; New York: Longman.

Luke, A., & Luke, C. (2000). A Situated Perspective on Cultural Globalization. In N. Burbules & C. Torres (Eds.), Globalization and Education: Critical Perspectives (pp. 275-297). New York: Routledge.

Macken, M., & Rothery, J. (1991). Developing critical literacy through systemic functional linguistics: A model for literacy in subject learning. Ersineville: DSP Printery: Produced by East Region Disadvantaged Schools Program.

Mackinnon, D., & Manathunga, C. (2003). Going Global with Assessment: What to do when the dominant culture’s literacy drives assessment. Higher Education Research & Development,, 22(2).

Martin, J., Christie, F., & Rothery, J. (1987). Social processes in education: A reply to Sawyer and Watson (and others). In I. Reid (Ed.), The place of genre in learning:current debates Center for studies in literary education: (pp. pp.58-82). Deakin: University Press.

Martin, J., & Rothery, J. (1986a). What a functional approach to the writing task can show teachers about ‘good writing’. In B. Couture (Ed.), Functional approaches to writing: research perspectives . (pp. 241-265). Norwoord, NJ: Ablex.

Martin, J., & Rothery, J. (1986b). Writing Project Report No.4. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Martin, J. R. (1989). Factual Writing: Exploring and challenging social reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Martin, J. R., & Rose, D. (2003). Working with discourse: Meaning beyond the clause. London: Continuum.

Moll, L. C. (1990). Vygotsky and education : instructional implications and applications of sociohistorical psychology. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Paltridge, B. (2001). Genre and the language learning classroom. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Ramanathan, V. (2002). The politics of TESOL education : writing, knowledge, critical pedagogy. New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

Rothery, J. (1996). Making Changes: Developing an Educational Linguistics. In R. Hasan & G. Williams (Eds.), Literacy in society (pp. xxi, 431 p.). London ; New York: Longman.

Schleppegrell, M. (2004). The language of schooling : a functional linguistics perspective. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Schleppegrell, M., & Colombi, C. (2002). Developing advanced literacy in first and second languages : meaning with power. Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

The New London Group. (2000). A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures (pp. 9-38). London: Routledge.

Thompson, G. (2004). Introducing Functional Grammar. London: Arnold.

Thomson, J. (2005). Theme analysis of narratives produced by children with and without Specific Language Impairment. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 19 (3), 175-190.

Trujillo, F. (NA). Uses of Spoken and Written English., June 2007

Warschauer, M. (2000). The Changing Global Economy and the Future of English Teaching. Tesol Quarterly, 34(3), 511-535. US ETS to Design Business English Test in China (2002). People’s Daily. from http://english.people.com.cn/200207/10/eng20020710_99450.shtml. Retrieved June 26, 2007

Appendix 1: Analysis of Theme/Rheme in the Two Texts

Text 1 (Diana Chase’s essay):

Marked Theme = Italics; Unmarked Theme = Underlined; (Ellipsis)

The popular adage “It Pays to Be Honest” Is a true statement, but (it is) not an applicable one in today’s world. If no one acted dishonestly, much of life’s daily pain and misery would cease to exist. Lies and deceit only serve the prevaricator and no one else.

Dishonesty takes many forms in today’s society from the harmless lie a small child tells his parents to serious felonies like robbery and rape. Each lie or evasive maneuver is driven only by a selfish need. People are born selfish and (people) must be taught to share, to look beyond their own survival to the survival of their community as a whole. This is a difficult thing to do as it is human nature to survive by any means necessary.

Take the case of the child lying to his parents. Say the child breaks a vase and when the parents ask what happened, he will probably answer “the vase got broken”. This is a way to avoid being blamed for the vase’s demise since the vase could have been broken at any point. As a form of survival, although the parents are quite aware of what happened, the child feels safe in that he cannot be held responsible.

Someone who steals. has far bigger motives than to escape the wrath of an upset parent. He may need money, or (he) is looking for attention from friends who egg him on, or perhaps he just steals for the adrenaline rush it affords him. Even so in this way his motives are selfish and his actions are damaging. The robbery will affect a greater population than the broken vase. The only positive outcome will be the fulfillment of the criminal’s goal.

In both cases the statement that dishonesty is selfish is supported. If everyone acted honesty the eventual benefit would serve the entire community. The one person who behaves altruistically is not directly benefited by his actions until someone else decides to sacrifice for the common good as well. Honesty is only beneficial to everyone as a whole if all selfish motives are left behind. 348 words

Text 2 (a Chinese student’s essay):

Marked Theme = Italics; Unmarked Theme = Underlined; (Ellipsis)

In today’s commercial world, whenever you go, you will hear people complain about people’s dishonesty. On campus, people are talking about students’ cheating in exams; in job market, the employers are troubled with confusing false credentials; and in shopping areas, customers are worrying about the many fake commodities they can never protect them from buying. In a word, there is cheating and dishonest practice in every walk of our life.

Why does dishonesty prevail so much? There are, to my mind, plenty of contributing causes, among which, the following ones are particularly worth mentioning. First, competition is always so fierce everywhere, from campus to company, and from job market to supermarket. Second, people are attaching so much importance to the improvement of their material life that they neglect the development of the spiritual and moral values, and consequently, they do a lot of things insensibly. And finally, we lack powerful and effective laws, rules and regulations to fight against this social problem.

It pays to be honest in the long run, and honesty will do good to both the honest people themselves and everybody else. To be exact, honesty will bring you friends and business partners, and thus (honest will) bring you happiness and fortune. Besides, to behave ourselves is to behave in an honest way. And what’s more, being honest is the essential step towards spiritual civilizaiton. Therefore, let’s remember that “honesty is always the best policy”. (236 words)

Appendix 2: Analysis of Cohesive Devices

Text 1 (Diana Chase’s essay) Iterative progression (repetition or co-reference of theme in subsequent clauses = Italics); Linear progression (Theme of clause derived from rheme of earlier clause) = Bold Black; (Ellipsis)

1The popular adage “It Pays to Be Honest” is a true statement, but (1it is) not 1an applicable one in today’s world. 2If no one acted dishonestly, much of life’s daily pain and misery would cease to exist. 2Lies and deceit only serve the prevaricator and no one else.

2Dishonesty takes many forms in today’s society from the 2harmless lie a small child tells his parents to 2serious felonies like robbery and rape. 2Each lie or evasive maneuver is driven only by a selfish need. 3People are born selfish and (3people) must be taught to share, to look beyond 3their own survival to the survival of 3their community as a whole. This is a difficult thing to do as it is 3human nature to survive by any means necessary.

Take 2the case of the child lying to his parents. Say the child breaks a vase and when the parents ask what happened, he will probably answer “the vase got broken”. This is a way to avoid being blamed for the vase’s demise since the vase could have been broken at any point. As a form of survival, although the parents are quite aware of what happened, the child feels safe in that he cannot be held responsible.

Someone who 2steals has far bigger motives than to escape the wrath of an upset parent. He may need money, or is looking for attention from friends who egg him on, or perhaps he just steals for the adrenaline rush it affords him. Even so in this way 2his motives are selfish and 2his actions are damaging. 2The robbery will affect a greater population than the broken vase. The only positive outcome will be the fulfillment of 2the criminal’s goal.

In both cases the statement that 2dishonesty is selfish is supported. If 3everyone acted 1honesty the eventual benefit would serve 3the entire community. The one person who 1behaves altruistically is not directly benefited by 1his actions until someone else decides to sacrifice for the common good as well. 1Honesty is only beneficial to 3everyone as a whole if 2all selfish motives are left behind.

Text 2 (a Chinese student’s essay): Iterative progression (repetition or co-reference of theme in subsequent clauses = Italics); Linear progression (Theme of clause derived from rheme of earlier clause) = Bold Black; (Ellipsis)

In today’s commercial world, whenever you go, you will hear people complain about people’s dishonesty. On campus, people are talking about students’ cheating in exams; in job market, the employers are troubled with confusing false credentials; and in shopping areas, customers are worrying about the many fake commodities they can never protect them from buying. In a word, there is cheating and dishonest practice in every walk of our life.

Why does dishonesty prevail so much? There are, to my mind, plenty of contributing causes, among which, the following ones are particularly worth mentioning. First, competition is always so fierce everywhere, from campus to company, and from job market to supermarket. Second, 1people are attaching so much importance to the improvement of their material life that they neglect the development of the spiritual and moral values, and consequently, 1they do a lot of things insensibly. And finally, we lack powerful and effective laws, rules and regulations to fight against this social problem.

It pays to be honest in the long run, and 2honesty will do good to both the honest people themselves and everybody else. To be exact, 2honesty will bring you friends and business partners, and thus (2honest will) bring you happiness and fortune. Besides, 2to behave ourselves is to 2behave in an honest way. And what’s more, 2being honest is the essential step towards spiritual civilization. Therefore, let’s remember that2 “honesty is always the best policy”.

Appendix 3:

Resources for Teachers on Genre Based Pedagogy

First Steps Literacy 2nd Edition: Teacher Resource Books http://www.stepspd.com/us/resources/ firststepsliteracy.asp

English Online is a site for English teachers (years 1-13) which includes student projects, teaching resources, networks and research for teachers. http://english.unitecnology.ac.nz/

The New Zealand Curriculum Exemplars provide assessment guides for written, oral, and visual language development. http://www.tki.org.nz/r/assessment/exemplars/eng/

Hyon, S. (1996). Genre in Three Traditions: Implications for ESL. Tesol Quarterly, 30(4), 693-722. Provides a useful map of genre traditions as well as their favored teaching applications. Also see Paltridge 2001, Knapp and Watkins 2005, and Derewianka, B. in references.

THE AUTHORS

Qian Yang is a faculty member with the College of Foreign Languages at Shaanxi Normal University. She holds a Master’s degree in Applied Linguistics. Her research interests include Second Language Acquisition.

E-mail: qyang@educ.umass.edu

J. Andrés Ramírez is a Doctoral Candidate in the School of Education, University of Massachusetts-Amherst. His research interests are theory and methods in ESL/EFL, Educational Discourses and the teaching and learning of academic language and content to diverse students, Critical Discourse Analysis and Critical Literacy

E-mail: jaramirez1971@yahoo.com

Ruth Harman is a Doctoral Candidate and ACCELA Fellow in the School of Education, University of Massachusetts-Amherst. Her research interests are in Systemic Functional Linguistics, Critical Literacy and Teacher Education Urban School Contexts.

E-mail: rharman@educ.umass.edu

Creation date:

Métricas

Licencia

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/