DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.165Published:

2005-01-01Issue:

No 7 (2005)Section:

Research ArticlesThe design of reflective tasks for the preparation of student teachers

Keywords:

preparación de futuros docentes, educación de profesores, práctica docente, supervisión, práctica reflexiva, observación, escritura de diarios, conferencias, aprendizaje de estudiantes practicantes (es).Keywords:

pre-service teacher preparation, teacher education, observation, journal writing, conferences, supervision, reflective practice, reflective tasks, student teachersʼ-learning. (en).Downloads

References

Barlett, L. (1990). Teacher development through reflective teaching. In Richards, J. & Nunan, D. (eds). Second language teacher education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 202-215.

Britten, D. (1985). Teacher Training in ELT (part I). Language Teaching, 18(1), pp. 112-127.

Cárdenas, R., and Faustino, C. (2003). Developing reflective and investigative skills in a teacher preparation program: the design and implementation of the classroom research component at the foreign language program of Universidad del Valle. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal . No.6, pp. 22-48.

Gerard, G., and Ellinor, L. (2005). Dialogue defined. Available at http: // www.the dialogue grouponline.com/whatsdialogue.htm/·dialogue.

Loughran, J. (2002). "Effective reflective practice". Journal of Teacher Education, 53 (1), pp.33-43.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (1994), Ley General de Educación, Bogotá.

Pentimalli, B. (2005). Observation in situ within ethnographic field research. Available at http: // www-sv.cict.fr/cotcos/pjs/methodologicalapproaches/data gatheringmethods/gathering paperpentimalli.htm.

Pollard, A. and Tann, S. (1993). Reflective teaching in the primary classroom. London: Wellington House.

Richards, J. and Ho, B. (1998). Reflective thinking through journal writing. In Richards, J. Beyond training. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.153-170.

Richards, J. (1998). Beyond training. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rodgers, C. (2002). Voices Inside School. Seeing Student Learning: Teacher Change and the Role of Reflection. Harvard Educational Review, 72/2, pp.230-250.

Short, C. & Burke, C. (1996). Examining our beliefs and practices through inquiry. Language Arts, 73 (2), pp. 97-103.

Shulman, S. and Shulman, J. (2004). How and what teachers learn: a shifting perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36 (2), pp. 257-271.

Viáfara, John, (2004) Student teachers' development of pedagogical knowledge through reflection, [unpublished masters thesis, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá, Colombia.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2005 vol: nro:7 pág:53-74

Rsearch Articles

The Design of Reflective Tasks for the Preparation of Student Teachers

John Jairo Viafara

E-mail: jviafara@yahoo.com

Abstract

The preparation of student-teachers to face the beginning in their profession requires from us, teacher educators, enriching discussions to share what we know and to build more solid grounds in our area. On the following pages, I describe how, in the specific context of a public university, I have designed and implemented a set of tasks within a reflective framework to support student- teachers' learning in their practicum. In this regard, a detailed explanation of how journal writing, conferences, focused reflection on tasks and responses to observation notes is included. Likewise, the experience of a student teacher working with tasks to solve a difficulty in the practicum, contributes to illustrate how reflective exercises support her development.

Key Words: pre-service teacher preparation, teacher education, observation, journal writing, conferences, supervision, reflective practice, reflective tasks, student teachers'-learning.

Resumen

Preparar a los estudiantes en la práctica docente para lograr que éstos puedan enfrentar su comienzo en la profesión, requiere de nosotros, educadores de p rofesores, una discusión significativa en la cual se comparta lo que sabemos y sea posible construir bases más sólidas en nuestra área. A lo largo de las siguientes páginas, describo como en el contexto de una Universidad pública he diseñado e implementado un conjunto de tareas dentro de un enfoque reflexivo para apoyar el aprendizaje de los futuros profesores en la práctica docente. A este respecto, incluyo una explicación detallada de como la escritura de diarios, conferencias, tareas específicas y repuestas a las notas de observación del consejero son utilizadas. Además, la experiencia de una estudiante de práctica quien emplea las tareas para resolver una dificultad, contribuye a ilustrar como los ejercicios reflexivos apoyan su desarrollo.

Palabras Claves: preparación de futuros docentes, educación de profesores, práctica docente, supervisión, práctica reflexiva, observación, escritura de diarios, conferencias, aprendizaje de estudiantes practicantes.

Introduction

The specific context of a public university has shaped and widened my understanding of the student-teachers' process to become competent professionals. As a counselor and recent researcher who works with pre-service teachers, I have planned, designed and revised a set of tasks which respond to the conditions that student-teachers experience during their practicum. The exercises, as pieces of a reflective approach for prospective teachers' preparation, aim to contribute to the development of teaching knowledge and professional attitudes.

I will start by describing how specific conditions in the context of my experience influenced the ideas I had for planning the tasks. I will continue by presenting the theoretical pillars that support the structure of my design. Then, I will describe the set of tasks and tools through which student-teachers interact among themselves, their counselors, their peers and their teaching reality to develop their initial practice. Finally, I will present the conclusions and implications of this reflective process.

Observing the conditions of a public university setting

The teacher licensing program, within which , I have developed the preservice teacher preparation experience at a public university, provides only one semester for the practicum. During these months, prospective teachers work through, basically, two main fronts. First, they are assigned a group of students at primary, secondary or university levels and teach the group an average of four hours each week. Furthermore, as part of their assignment at school, prospective teachers are encouraged to become part of the institutional context by attending meetings as well as cultural and social events.

The second experience student-teachers encounter relates to their participation in counseling sessions. They are assigned a counselor who deals with the formal aspects that regular subjects imply such as planning conferences, workshops and assessing student-teachers' performances to help them in their preparation. Approximately five prospective teachers work with a counselor by attending two-hour weekly meetings with him/her.

The sessions to guide and support prospective teachers deal with issues related to lesson planning, classroom management, teaching methods, syllabus development and evaluation; moreover, some sessions are used for discussing formal aspects concerning the functioning of the schools' structures, including the existing laws on education in our country.

All in all, the two-hour counseling sessions are devoted to providing student- teachers with feedback from class observations made by the counselor, which implies her/his analysis and reflection upon the issues mentioned in the previous paragraph. Finally, these short sessions seek to support students in their development of professional attitudes and emotional relief toward overcoming fears and anxiety.

The previous description reveals a common situation in many pre-service teacher preparation programs in public Colombian universities: existing resources seem not to be enough to satisfy the needs of a growing number of students in these institutions. That is why specific conditions that could limit the development of future teachers are likely to emerge. For instance, in many public universities, a significant number of student-teachers are assigned to only one counselor for guidance in their preparation. In other cases, the amount of time for tutoring future teachers is not enough. Additionally, adopting prescriptive approaches in search of quick results appears to be a more suitable choice than, let us say, a reflective approach. Last but important, the deterioration of our society that is reflected in the increasing number of difficulties that students bring with them to schools reveals the need for teacher education paradigms to support future teachers' development of solutions based on particular contexts.

Since the first semester, when I started working with prospective teachers in the context of a public university, I came across a considerable number of publications that provide ideas to plan or create these sorts of courses. I studied student-teachers' learning processes to build tools and strategies that could function in the Colombian context such as the one described above. In this regard, Strevens (1974, as cited by Britten, 1985) emphasizes the role of realism in relation to the requirements of the system, the time and training resources, among other aspects, as crucial elements for teacher training in ELT.

In Colombia, we specifically face the challenge of new views in the preparation of students which calls for more autonomy, resourcefulness and development of critical skills so that students can cope with the limitations we face in our system. Consequently, as stated in the General Law of Education (1994, Ley 115), higher education needs to foster reflection in learners so they can become more autonomous as adults or later in their professional practice.

Bearing in mind the above mentioned data, I adopted a reflective approach to mold the tools and tasks I had designed for the practicum in the context of my university since time and resources are constraining factors. The tenets of this educational philosophy are summarized in the next section.

Reflection in shaping the tools for a preservice teacher- preparation experience

Working with reflection, as the big umbrella term, has led me to make use of inquiry to plan tasks. The following paragraphs summarize fundamental ideas in each of these two educational views and their relation to one another.

Barlett, (1990:204) refers to the relation between an individual's thought and action as fundamental in the idea of reflection. Hence, reflection emerges as a deep thinking process which includes the deliberation student-teachers become involved in as they look at their ideas and teaching actions critically. Additionally, this deliberation involves an attitude of openness, honesty and determination to examine repeatedly one's ideas and teaching actions in the interplay of the "self" and those things that surround it. In the particular case of student-teachers, the ideal situation would be that their thinking, intentions and actions interact with their background knowledge to substantiate their learning. In this regard, reflection would not only happen in connection to reasoning, but would also translate into a concrete teaching performance, making experiences more meaningful for prospective teachers.

Several authors, among them Barlett (1990), Wallace (1991), Pollard and Tann (1993) and Rodgers (2002), as well as my own research for my master's thesis (2004) have proposed reflective cycles, which are a series of stages to explain how teachers develop a reflective practice. From these proposals, I would like to point out the following common notions that have been of use in my design to show how reflection can become a learning tool in teacher preparation. It is difficult to draw a line to mark the boundaries of the following aspects for a reflective teaching practice. Essentially, each element supports the others and they overlap as practitioners go back and forth on their learning road.

- Knowing about one's own teaching through collecting information and developing skills to become aware of how one does one's job.

- Self-appraising our teaching which implies being critical of ourselves to understand and connect the implications of our past actions to our future performance.

- Planning, which entails analysis to explore different possibilities and make decisions.

- Acting as the improvement of one's practice based on information from each of the previous steps.

With the purpose of adding an important element to the previous ideas concerning reflection, I have considered Loughran (2002:33), when he expresses that ";one element of reflection that is common to many is the notion of a problem. What that problem is, the way it is framed and (hopefully) reframed, is an important aspect of understanding the nature of reflection". It is precisely the notion of problem, as a puzzling situation, which seems to be for some authors the connection point between reflection and inquiry. Gerard, and Ellinor, (2005), for instance, mention, "inquiry and reflection are about learning how to ask questions with the intention of gaining additional insights and perspectives. Through this process, we dig deeply into matters that concern us and create breakthroughs in our ability to solve problems". Similarly, the use of the reflective tools I have prepared for student-teachers has involved participants not only in looking for answers to their problems, but also in asking their own questions.

To be a little more specific concerning inquiry, I would include that it is a tool to know about one's teaching through observation and self-evaluation. Short and Burke (1996) regard inquiry as the process teachers go through to explore their beliefs and actions, an exploration which naturally relates to change. In this regard, teachers can define a clear problem or question about their own job and then look for answers. Nonetheless, inquiry is not just about the teacher who wonders about his or her beliefs and actions. It also deals with the teacher who is critical of him/herself and is constantly interested in looking for different possibilities to transform his or her behavior based on reflection. Wells (2002:198) summarizes a general concept of inquiry as "knowing, acting and understanding".

Recently, in the area of preservice teacher education, educators have tried via several projects to incorporate strong components based on inquiry and reflection. In our country, for instance, Cárdenas and Faustino (2003) have documented their experience involving student-teachers in classroom research. Their findings about the use that prospective teachers make of observation and diaries point towards the crucial role that these reflective tasks have played in the development of self-awareness, analytical and critical skills for teaching.

The previous ideas on the process of reflection became the spinal cord of most of the tasks and tools I have integrated in the practicum. The next section includes a detailed outline of those tasks and how they have been used.

The shape of reflective tasks in a practicum experience

The four kinds of tasks, which I describe in this section, have been conceived under a reflective approach. Therefore, each of them is an integral part of a working plan to support student-teachers' reflective practice. Similar, to other kinds of tasks, these reflective tasks have been designed as an exercise to pursue the development of a process rather than the consecution of a product. As will be seen, the tasks can take participants through several stages which are related to the "ingredients for a reflective practice", explained along the previous section.

The preparation of meaningful learning and teaching tools or tasks requires not only designing, finding or adapting these pedagogical aids, but also integrating those tools among themselves so that they work smoothly, generating an enriching experience. In order to show the coherence of tasks working together, I will concentrate on the process of a particular student- teacher facing a difficulty during the term. Furthermore, I will include the voices of other student-teachers in connection with their impressions as they made use of my observation notes, focused on reflection tasks, their journals and our conferences. Students' real names have not been used; still, each of them provided me with their written consent to use their notes and testimonies.

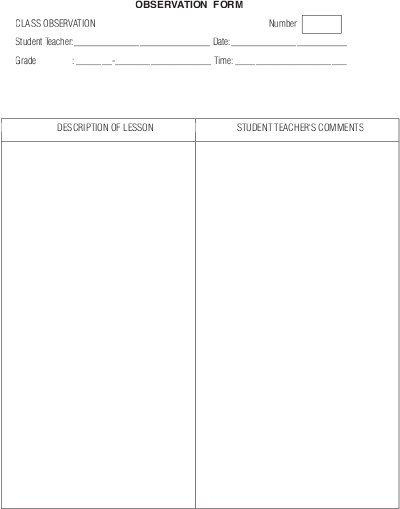

Responses to observation notes

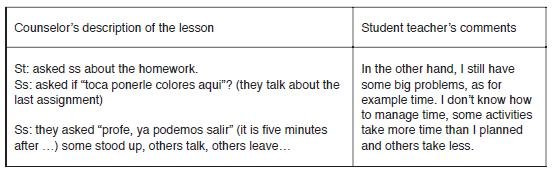

I write observation notes to describe student-teachers' situation and actions within the classroom. The instrument to serve this purpose is a very simple form that I have designed which saves a whole column to allow student-teachers' reflections (see Appendix A). I use ethnographic notes (Pentimalli:2005), thus avoiding prejudging to describe what happens during the lesson I observe. Then, right after the lesson, I hand the notes to the student-teacher and he or she is asked to read the description of the lesson and react to it by writing comments, questions, concerns and so on. Finally, they are requested to take the form back to me for my perusal before our individual conference.

Sofia, a student in eighth semester, was enthusiastic but also afraid of working with children in her teaching practice. In the particular situation provided in the form below, Sofia’s lesson had ended a few minutes earlier and she was trying to deal with some final issues.

(Response in observation worksheet, March 20, 2003, n.2)

The previous reaction to my notes seems to reveal that Sofia has become aware of her need to manage time better. Possibly, her responding to my notes has guided her to self- appraise, one of the core components in reflection.

As a testimony to evidence the role of Sofia's use of my notes in her practice, I recall here one of the comments she wrote at the end of the term:

"They (the notes) made me reflect about my role as teacher because it showed me the importance of the different issues we have to take into account when we are teachers, I mean the importance of my attitude during the class, the right preparation of the activities and so on".

(Questionnaire, June 10, 2003)During the term, she also reacted to my notes by writing questions, describing situations that had happened at a time other than the lesson time pictured in the form but that were related somehow, listing actions she had taken to cope with difficulties, expressing her feelings, suggesting possible actions to improve and recalling theoretical principles, among others.

Sofias' answers relate to Richards (1998), who considers observation to be a reflective practice which provides teachers with data to understand the source and reasons for their actions. Consequently, the knowledge student-teachers gain about themselves is a point of reference for them to constantly transform their programs. Precisely, other exercises such as the ones I described in the following lines can guide preservice teachers to relate their observations of themselves, their realization of what they need and their quest for possibilities to make a difference in and through their teaching.

Focused reflection tasks for teacher improvement

I have designed several reflective tasks from theory that should provide student-teachers with valuable information for their learning during the practicum. An example for how this can work was the theory I found in Wong and Wong (1998) regarding how teachers make use of time in classes. Based on that, I designed a self-observation worksheet (see Appendix B). Student- teachers are asked to read theory about the use of time, and then they write what they think their use of time in class might be. Afterward, they actually observe themselves teaching, and contrast their perceptions and reality. During the exercise they move beyond observation to a more critical look at themselves and the exploration of possibilities to help themselves with this issue.

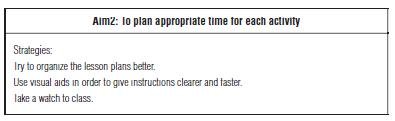

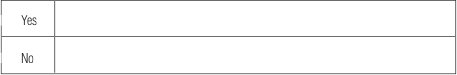

Another task I have designed concerns with setting goals. Student- teachers are invited to look back at their own performance and to establish two goals related to aspects they consider they need to improve on. Since prospective teachers pose their problems or questions through goals and look for solutions, the exercise involves their inquiring about their teaching. To begin with, I provide student-teachers with a form (Appendix C) so they can, in the first place, go through a certain reflection that implies making connections with contextual issues of the practice behind their goals. The previous activity requires student-teachers’ detailed consideration and recollection of situations when the difficulty tends to occur. A second stage takes place when prospective teachers propose possible courses of action to reach their goals. Finally, after a reasonable number of weeks, preservice teachers receive a follow-up worksheet to monitor themselves (see Appendix D), which helps them find out if the actions they have taken to improve are working. Later, when they realize they have accomplished their objectives, they can add new ones.

In the case of Sofia, whose responses to my observation notes (see the previous section) expressed her concern about managing time properly, some of her answers in the task of setting goals evidence how this exercise guides her to a coherent planning of future actions. She wrote the following in her worksheet:

The way a task functions in itself and connects to others reveals how these preservice teachers can not only discover useful aspects about their teaching, but can also consider possible alternatives for action. In this regard, Wink (2000) mentions that "transformation is possible because consciousness is not a mirror of reality, not a mere reflection, but is reflexive and reflective of reality" (p.113).

The strategies student-teachers planned and implemented are monitored by themselves through several reflective exercises. For instance, journal writing, as will be shown in the following section, plays a paramount role in supporting their self-evaluation.

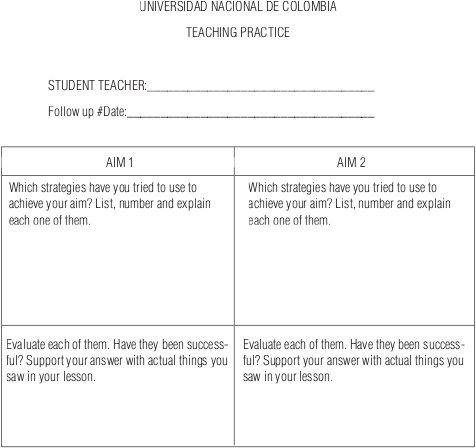

Journal writing

Traditionally, journals have been widely used in teacher education courses to provide participants with an opportunity to engage in one of the most successful manners of reflection: dialoguing with oneself or someone else. In relation to this, a student-teacher expressed the following: "I consider it was the best tool for me because it helped me to reflect a lot about my own process and it was also a good way of keeping in touch with my counselor". (Individual ( conference, November 24, 2004) Of course, prospective teachers not only 2004 share their journals with me, but also among themselves. Exchanging their writing takes place a couple of times a month, so I or their peers can react by answering or posing questions, providing suggestions, narrating experiences, agreeing or disagreeing and so forth. There are some other guidelines related to principles that student-teachers can take into account about journal writing which are given to them at the beginning of the term (see Appendix E).

Again, flexibility is important since pre-service teachers need to perceive their journal as something close to them, an item with which to engage in a frank analysis of their teaching. Thus, providing multiple choices regarding how to keep it as well as when to share it and with whom, can make a significant difference.

In the following extract from Sofia’s journal, one sees her openness to revise her own strategy (stated in her reflective task of setting goals) in order to solve her concern in relation to the appropriate use of time.

"Today I brought different visual materials in order to make more comprehensible the topic; however, I noticed at the end of the class that they hadnʼt understood completely the topic. So, I suppose next time Iʼll have to work harder in the method to explain the topics". (Journal, April 17,2003).

The previous extract relates to Richards and Ho (1998) in the article, "Reflective thinking through journal writing", when they comment that "the goal of activities like journal writing is to engage teachers in a deeper level of awareness and response to teaching" (p.162).

Journal writing, along with the other reflective tasks mentioned so far in this article, not only facilitates student-teachers’ reflections, but also informs the counselor so he/she can arrange meetings to address student-teachers’ needs and expectations. Let us see in the following paragraphs how conferences become an important part of this practicum experience.

Individual and group conferences

In general, conferences refer to one-hour weekly meetings that student- teachers and I hold. Ideally, they can take place as soon as the student-teacher’s lesson ends, so it is not difficult to remember events from the observed class. Counseling sessions involve discussions about the planning and implementation of lessons, readings, and materials, among others. The following features that I take into account to support reflection in conferences are fundamental:

- Previous reflection tasks serve as a diagnosis to plan the content of the conference. For instance, student teachers and I analyzed the journal and their responses to my observation notes before the session and we might later return to the deliberation included in those tasks during the meeting.

- The creation of a relaxing atmosphere focusing the conference on student- teachers’ priorities and allowing prospective teachers to enjoy free expression. Student-teachers explain and describe teaching and school issues while the counselor provides feedback through different means and support. The counselor should be a very good listener who fuels the conversation via comments or questions and avoids stopping or interrupting participants.

- The involvement of participants in the use of inquiry. Not only should the counselor inquire, but also the student-teacher who needs to pose the problem and to solve it. Otherwise, in our role as counselors, we would be imposing and if that happens, we could not talk about reflection.

- Finally, the conference ends revealing clear conclusions, as well as ideas to be taken into account.

Offering individual or group alternatives to holding conferences seems a relevant issue in order to foster an honest dialogue between counselor and student- teachers. The individual conference represents a space for prospective teachers where they can openly mention issues which could be embarrassing if mentioned in public. On the other hand, some student-teachers might prefer the group conference as in the case of the following teacher who said:

"I feel there is an advantage in the group conference because sometimes when we are not close to the practicum counselor, it is difficult in the individual conferences to tell what I am thinking and in the group conference that person can hear the experience of other students and that person feels relief because he/she says o.k, thatʼs something that is not just happening to me but that I can share with other people". (Interview, February, 2005)

The example below shows the interaction between Sofia and her counselor as she moves forward in her need to manage time better in classes. See (AppendixF) for conventions used in the transcription of conferences.

C:... my impression was that time was a priority for you too, finishing your lesson plan for example, but ...which things can help you?

S: To control the class, have a nice environment, to... donʼt spent so much time working on getting kids silent, ... to use different methodologies in which they can work easily and concentrate on the activity, but not doing some talking and interrupting the classes always because they are talking or they are playing...etc

C: ... It seems you know some answers here... do you see anything else?S: Yes, we have to be constant, also I noticed that it is better if we use graphic symbols or things that they enjoy, for example, not only words but also graphics or something like that...

(Individual conference, May 30, 2003)

Sofias’ counselor’s questions provided an opportunity for her to brainstorm concerning possible causes of her problem and to fuel her initial exploration for alternatives to plan strategies.

Turning to group conferences, Shulman and Shulman (2004) state that "through discussing their work from curriculum design to classroom teaching and assessment we aim to enhance teachers’ capacities to learn from their own and one another’s experience" (p.264).

In the following extract from a conference, it is noteworthy how Sofia’s thoughts, along with one of her peer’s observations, build a bigger perspective regarding the use of time in class; Amanda and Sofia connect it to lesson planning.

A: Iʼm always keep in mind those problems, because I always tried to organize the lesson plans but ... if Ss doesnʼt work you have to do something new, but if that doesnʼt work, so you have to create another thing to improve the...

Ca: in that moment

C: to improvise a little... o.k.

S: o.k. I think that the lesson plan to have a general idea of the class, but it changes a lot, for example, we plan different activities, but in the moment we have to choose some, the most appropriate , the kind of activities that they enjoy the most...

C: in our case, was it easy for you to be flexible or how important for you was to follow a lesson plan?

S: oh!, it was difficult, it was very difficult for me, also because I was very concerned with the time. It was for me something important, but I always take that into account.

(Group conference, June 5, 2003)

Student-teachers’ interaction in this conference exemplifies the kind of support and contribution that peers can provide each other in their understanding of teaching. Amanda and Sofia discussed how they had realized that the plans they make for their lessons might change. This commonality, their idea about flexibility in lesson planning, is the focus that the counselor takes and which, at the end, Sofia relates regarding her concern about managing time in the lessons.

After the description of simple and practical reflective tasks and their use for student-teachers’ preparation in their practicum, I will close by pointing out several guidelines which might be relevant for the creation of meaningful experiences to support the learning of future teachers.

Conclusions and implications

The design of reflective tools and tasks for pre-service teachers during their teaching practice can be a meaningful support for them when contextual conditions are taken into account. For me, as someone involved in the preparation of student-teachers in a Colombian public university, a reflective approach has been satisfactory in order to cope with many of the constraints in terms of time, resources and the difficult social situation of school students that generates concern and anxiety in future teachers. Wink (2000) says, "those who live within a community, those whose have experienced a unique (social, historical, cultural, political) context, have an understanding that others do not have... they generate their answers based on their own context"( p.94). Using the knowledge that we have concerning the educational context in our country at university, secondary and primary levels, we teacher educators, can enhance our work with student-teachers during their teaching practice by implementing viable alternatives for their preparation.

In the proposal I have described, student-teachers use four reflective tasks during their teaching practice. They dialogue with themselves and others by means of a journal that they keep and share with their counselor and peers along the term. Furthermore, they respond to their counselor’s observation notes exploring their thinking and actions, which guides them towards a critical attitude about themselves. Furthermore, they develop focused reflective exercises to overcome specific difficulties. Finally, they engage in group reflection when they participate in conferences. They also gain support and different perspectives with which to build meaning for their teaching.

Considering the organization of tasks in an integrated perspective, in which each exercise is closely related to the next one, can provide more benefit to the learning and growth of student-teachers. A careful planning of how to arrange tasks might ensure constant nourishment in the process. The skills and knowledge student-teachers develop through each exercise are stepping stones to take them forward. Then, all the ensemble can result in coherent analysis, decisions and actions. In addition, the ongoing recycling process can strengthen what students learn and their skills as reflective practitioners are each time more adept at the understanding and confrontation of difficulties.

The process discussed in this paper, in which tasks are flexible enough to function based on each student-teacher’s needs, reveals the importance of putting student-teachers at the center of their own preparatory process. Prospective teachers can gain autonomy to make their own decisions and develop professional skills to cope with their future jobs.

The ideas included in the previous paragraph should lead us to revise our roles as teacher educators. Our role needs to go beyond a technical approach in which we give recipes to student-teachers and limit their learning by imposing "deal models". Leading students’ engagement in reflective thinking and action through tasks that promote questioning, dialoguing and self-awareness practices can enrich what we do to help future teachers.

Difficulties can also be part of the process to support prospective teachers’ learning through reflective tasks. During the experience that I had, using these exercises, I identified student-teachers’ system of beliefs as the biggest constraint that might keep them from engaging in reflective practices (Viáfara: 2004). In this regard, the exposure of student- teachers to traditional models of learning along their lives can lead them to trust only on those previous approaches. Thus, they expect for their counselors to provide them with the answers for their difficulties. Similarly, some prospective teachers do not seem to transform their reflective thinking into concrete pedagogical actions. Bearing the previous in mind, including tasks to foster student-teachers’ exploration of their beliefs, could make a difference in how they approach reflection for their learning.

REFERENCES

- Barlett, L. (1990). Teacher development through reflective teaching. In Richards, J. & Nunan, D. (eds). Second language teacher education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 202-215.

- Britten, D. (1985). Teacher Training in ELT (part I). Language Teaching, 18(1), pp. 112-127.

- Cárdenas, R., and Faustino, C. (2003). Developing reflective and investigative skills in a teacher preparation program: the design and implementation of the classroom research component at the foreign language program of Universidad del Valle. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal . No.6, pp. 22-48.

- Gerard, G., and Ellinor, L. (2005). Dialogue defined. Available at http: // www.the dialogue grouponline.com/whatsdialogue.htm/·dialogue.

- Loughran, J. (2002). "Effective reflective practice". Journal of Teacher

- Education, 53 (1), pp.33-43.

- Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (1994), Ley General de Educación, Bogotá.

- Pentimalli, B. (2005). Observation in situ within ethnographic field research. Available at http: // www-sv.cict.fr/cotcos/pjs/methodologicalapproaches/data gatheringmethods/gather- ing paperpentimalli.htm.

- Pollard, A. and Tann, S. (1993). Reflective teaching in the primary classroom. London: Wellington House.

- Richards, J. and Ho, B. (1998). Reflective thinking through journal writing. In Richards, J. Beyond training. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.153-170.

- Richards, J. (1998). Beyond training. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rodgers, C. (2002). Voices Inside School. Seeing Student Learning: Teacher Change and the Role of Reflection. Harvard Educational Review, 72/2, pp.230-250.

- Short, C. & Burke, C. (1996). Examining our beliefs and practices through inquiry. Language Arts, 73 (2), pp. 97-103.

- Shulman, S. and Shulman, J. (2004). How and what teachers learn: a shifting perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36 (2), pp. 257-271.

- Viáfara, John, (2004) Student teachers’ development of pedagogical knowledge through reflection, [unpublished masterʼs thesis, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá, Colombia.

- Wallace, M. (1991). Training foreign language teachers: a reflective approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wells, G. (2002). Learning for life in the twenty-first century. Oxford: Blackwell Publis- hing.

- Wink, J. (2000). Critical pedagogy. Notes from the real world. New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

- Wong, Hand and Wong, R. (1998). The first days of school. California,USA: Harry K. Wong Publications, Inc.

- Zeichner, K. (1983). Alternative paradigms of teacher education. Journal of Teacher Edu- cation, 34 (3), pp 3-9.

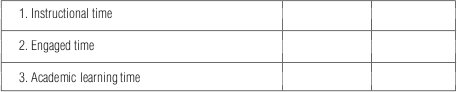

TASK HOW ARE WE USING TIME IN CLASS?

A. Write down in percentages how much it takes in your lesson:

B. For your next lesson:

- Keep in mind a clear realistic aim for this class, write it down:

- Did students accomplish what was expected in this specific time?

C. What did you do?

- Did you monitor students to keep them on task? How? Describe

- Do you think you use direct instructions (purpose and result of each step)?

- Who did most of the work in this class? Students? Teacher? (List the main actions students and teacher did/ include time.)

- How did you get students to focus at the beginning of class ? Was that effective? (Describe what happened at the beginning. )

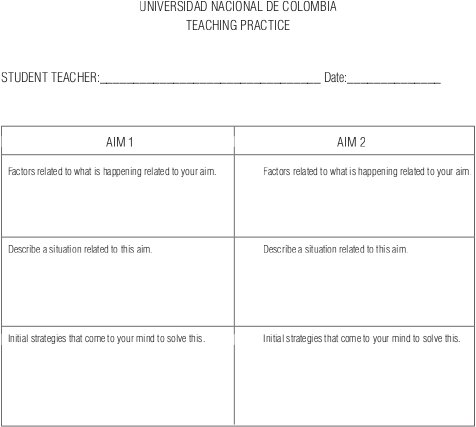

SETTING AIMS FOR IMPROVEMENT I

SETTING AIMS FOR IMPROVEMENT II

A journal has been incorporated as one of the tools to help you grow during your teaching practice. This constant writing can provide you with many insights into your own teaching. As you describe, specify, analyze events which took place during your practice, it should be easier to find answers to many of your own questions. Not only that, the journal is expected to be an additional means to communicate with your counselor. He might provide you with additional feedback on different concerns you might have. It can also be a document which might guide many of your professional interests in the future.

I hope this invitation to reflect and explore regarding your own thinking and actions can be fully accepted and used.

PROCEDURES FOR THE JOURNAL

- You can use any kind of notebook.

- Write an entry for each lesson or at least once a week.

- The audience for your writing is yourself, your counselor or a partner in our teaching practice group.

- As you write, keep some space where notes or answers can be written.

- S o m e o f t h e q u e s t i o n s w h i c h c a n g u i d e y o u r r e f l e c t i o n c o u l d b e :

Which were the aims/ expectations for the lesson? Were they achieved?

How effective was your methodology, materials, classroom management, new ideas?

What kind of interaction was set up? Did it work? Why not?

Could you follow your lesson as planned? Did you change things during the lesson, why?

Why do you follow certain methodology?

What kind of difficulties are more frequent? Why do you think these happen?

Did you discover anything new about your teaching?

How do you think you should change your teaching? Why?

Where did you get your ideas for teaching, organizing the classroom, dealing with students?

Do you like your job as a teacher?

IN TRANSCRIPTIONS

C: Counselor

S: Sofia

CA: Carmen

A: AliciaXXXXXXX: inaudible

( ): Explanation of a a key element in the situation

.... : silence

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.