DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.181Published:

2003-01-01Issue:

No. 5 (2003)Section:

Research ArticlesTeacher researchers as writers: a way to sharing findings

Keywords:

teacher research, writing teacher-research reports, in-service teacher education (en).Downloads

References

Christensen, C. and Atweh, B. (1998).`"Collaborative Writing in Participatory

Action Research". In Atweh, B., Kemmis, S. and Weeks, P. (eds.) (1998). Action Research in Practice. London: Routledge.

Benson, M. J. (2000). Writing an Academic Article: An Editor Writes... Forum English Teaching, Vol. 32, 2, pp. 33-35.

Burton, J. and Mickan, P. (1993). Teachers' classroom research: rhetoric and reality. Teachers Develop Teachers Research. Papers on classroom research and teacher development. Oxford: Heinemann.

Cárdenas, M. L. (2000). Action Research by English Teachers: An Option to

Make Classroom Research Possible. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal. Vol. 2, 1. pp. 15-26, Bogotá: Universidad Distrital.

Merriam, S. B. 1988. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

PROFILE. Issues 1, 2, 3. (2000, 2001, 2002). Bogotá: Foreign Languages Department, Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Torres, G. e Isaza, L. (2000). Evaluación de los Programas de Formación

Permanente de Docentes realizados en Bogotá entre 1996 y 2000. Bogotá:

IDEP` CEE.

Wallace, M. (1998) Action Research for Language Teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 2003-09-00 vol:5 nro:5 pág:49-64

Teacher researchers as writers: A way to sharing findings

Melba Libia Cárdenas B.

Universidad Nacional de Colombia

E-mail: mlcarden@bacata.usc.unal.edu.co

ABSTRACT

A teacher development programme (TDP) for teachers of English at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogotá has incorporated the rexsearch element as a means to motivate practitioners to widen professional knowledge. Based on the assumption that research findings gain real value if shared with other people, teachers have been challenged to establish a dialogue with academic communities by writing formal reports required by the University and articles describing the research processes they have accomplished. This paper examines the experiences of teacher researchers as writers as revealed in a research project in progress. I start by providing some background information about the TDP and then refer to the criteria that helped us to complete the writing tasks. Difficulties and strategies used to overcome them are also pointed out. Finally, I mention the benefits teachers identified after publishing their research reports in the PROFILE journal as well as some pedagogical implications.

RESUMEN

Un programa de formación permanente de docentes (PFPD) de inglés de la Universidad Nacional de Colombia ha incorporado la investigación como una forma de motivar a los docentes a ampliar sus conocimientos profesionales. Con base en la premisa de que los resultados de la investigación docentes a establecer un diálogo con la comunidad académica escribiendo reportes requeridos por la Universidad y artículos que describan los procesos investigativos adelantados. En este artículo examino las experiencias de profesores investigadores y escritores, las cuales se evidencian en un proyecto de investigación en curso. Primero informo acerca del PFPD y luego menciono los criterios que nos ayudaron a completar la labor de escritura. También destaco las dificultades y las estrategias empleadas para superarlas. Finalmente, menciono los beneficios percibidos por los docentes después de publicar sus reportes y algunas implicaciones pedagógicas. cobran valor en la medida en que sean divulgados, se ha motivado a los

KEY WORDS: teacher research, writing teacher-research reports, in-service teacher education

INTRODUCTION

Since 1995, I have written and coordinated in-service courses which integrate the aspects of language development, methodological updating and action research. This last component has been conceived as a tool to establish connections between the university classroom and the school teachers' realities. During the courses, and through report writing and oral presentations, teachers have expressed how much they value the experience of being a researcher. Nonetheless, I always felt that wider dissemination of teacher research was needed. This concern planted the seed to edit the PROFILE Journal in which school teachers could publish articles referring to their action research experiences and findings[1].

Having that goal in mind, I decided to include a series of changes in the courses: readings were assigned for extra-curricular work; writing was promoted through short tasks included in the course components (language development, methodological updating and action research); and most importantly, teachers were often reminded they were expected to submit partial and final research reports that could lead them to share findings by writing articles to be considered for publication in the programme official journal. Regarding this last aspect, I should point out that teacher educators in charge of the language and research strands played a paramount role as we set out to guide teachers in language use and research report writing respectively.

Besides keeping the PROFILE journal alive, several inquiries have emerged throughout this time concerning issues such as the contributions of action research when guiding practitioners to investigate their classrooms (Cárdenas, 2000). Another research project has focused on the nature of research undertaken by in-service teachers during 1998-1999 and 2000-2001 teacher development programmes22 A research project funded by the Research Division of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogotá (DIB) is currently examining the characteristics of teacher research (topics, methods, origins of teachers' inquiries), teachers' views about the effect or use of their research activity in their teaching practices and the impact research findings have had at schools.

Besides keeping the PROFILE journal alive, several inquiries have emerged throughout this time concerning issues such as the contributions of action research when guiding practitioners to investigate their classrooms (Cárdenas, 2000). Another research project has focused on the nature of research undertaken by in-service teachers during 1998-1999 and 2000-2001 teacher development programmes[2] A research project funded by the Research Division of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogotá (DIB) is currently examining the characteristics of teacher research (topics, methods, origins of teachers' inquiries), teachers' views about the effect or use of their research activity in their teaching practices and the impact research findings have had at schools.

- These two cohorts were chosen on the basis of their involvement in writing not only the reports required for the TDP, but mainly because they manifested their interest in submitting proposals for publication in the said journal.

RESEARCH METHOD

While examining the nature of teacher research I have followed the principles of qualitative case studies as this research method allows us to study groups functioning and to examine data grounded in the context itself (Merriam 1988). Thus, I have looked again at the teachers' research project reports and the field-notes I kept during those courses.

One of my purposes has been to make sense of what the experience of sharing results by publishing has been. Despite the findings from the field-notes and the reports, I felt it was necessary to delve into teachers' views after some time had elapsed. This, I thought, would give more reliable information as what they said when we evaluated the TDPs could have been affected by the emotion of the farewell, the enthusiasm produced by a fulfilled goal, or just the satisfaction of seeing one's paper printed in a journal. Then, in order to have a more complete picture, I also gathered information through a survey which searched for achievements, difficulties and strategies used to overcome them (see survey sample in appendix 1).

FINDINGS

As described in the following sections, data analysis has revealed that we require specific criteria for effective writing task completion. It has also shown a series of difficulties faced in the process; the mechanisms that helped us achieve our goals, and the gains of the said experience.THE WRITING PROCESS: WHICH CRITERIA FOR EFFECTIVE TASK COMPLETION?

TDPs are often conceived as opportunities for skill enhancing, pedagogical updating, professional reassurance, or certification. It has also been observed that most programmes incorporate writing as a requirement for course completion, but not from a publishing perspective. A study aimed at evaluating TDPs carried out in Bogotá between 1996 and 2000 found, in relation to the creation of teacher communities, that 71% of the participants in those programmes had not written documents to be published (Torres and Isaza, 2000). This shows that writing is not a common practice among teachers. As far as those programmes that reported publications by teachers, the topics included community education, maths and reading, but not English. The study concludes that the policy intended to foster writing culture and teachers' publications does not show significant achievements (pp. 65). This might be connected to lack of practice.

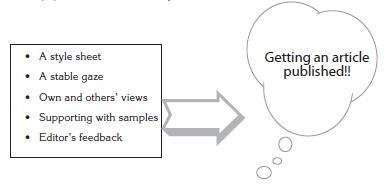

Being aware of writing difficulty or practice, and in order to guarantee effective task completion, I have consolidated a series of criteria which have been useful as a framework for report writing and journal editing for, as one teacher stated: "we need very precise steps to write the whole article" (Sonya).

Using style sheet. In the last phase of the in-service programme, and while teachers were writing the final report of the project or editing it to incorporate the research tutor's feedback, we came up with possible standards for article writing. This was done to guarantee some uniformity and an appropriate layout in the papers. To do so, we analysed several articles, noted down common

Fig. 1. Criteria for effective article writing completion

features and discussed a possible structure for the reports. Moreover, it was pointed out that papers need contextualisation, clarity, analysis, theoretical support, and a strong conclusion.

Though participants completed research projects, very often I observed a superficial topic analysis of the written reports which revealed the twists and turns that teacher-researchers took. It was then pointed out that, as Benson (2000) stresses, the major impact of any article lies in the strength of its analysis and interpretation. In view of this, it was also necessary to incorporate sections discussing research findings together with evidences from the action field.

Having a style sheet seemed to work for most teachers, who could count on a practical framework. However, as I will mention later on in this paper, several difficulties appeared and teachers as well as advisors had to look for options to overcome them.

Sustaining a steady gaze. It was clear from the beginning that the primary audience for the articles was other teachers. This implied keeping in mind the nature of the journal so that papers matched readers' interests and expectations and writing the articles in a comprehensible manner -in ways that academic reports often do not. In view of this, and in order to make texts appealing, we concluded that the reports should be written in a narrative style which should reflect the teaching context. It was then necessary to contextualise the focus of the article as accurately as possible to generate some sort of familiarization with the environments the papers refer to.

Telling the story by integrating own conversation and relevant literature in the field. When reporting on our experiences, we move along a continuum: either we provide plenty of details or we presuppose that the audience will get the complete picture of what we are saying by providing some information we consider sufficiently relevant. Having a balanced style challenges our capacity to tell relevant but concise stories. In our case, it was necessary not only to describe the pedagogical and research processes, but to support them by letting our style flow. As some teachers admitted, it was difficult to summarise issues explained in detail in the research report but which needed to be shortened for the article: "It was difficult to express ideas effectively and briefly¡ (Luz Marina); ´It is very difficult to summarize the experiences" (Magda); ´It was difficult to say it shortly; I mean we did not have much room to say everything we had done¡ (Diana). This difficulty was also found in the writing of the abstract: ´It was difficult to write the abstract because I thought everything should be there. So, writing the synthesis was difficult¡ (Sandra).

As far as relevant literature in the field, I had to work on the fact that many teachers' first drafts did not contain information about the key concepts or theories on which the study was based. Throughout the tutoring sessions I noticed that there was some apprehension to include others' views. Then, when I commented this finding with the teachers, they admitted some fear: If their paper had a theoretical section or many references to other authors, readers would not find any value in the paper. Searching articles in different journals and confirming the importance of not just telling the story but supporting it with previous and relevant studies was particularly useful to merge literature review and theories confirmed or discovered by the teachers. In addition, it was stressed that, as suggested by Wallace (1998), "the most important thing to remember about using sources is that you have to use them -don't let them use you!... whatever you write, has to be driven and organised by your own ides, and whatever message it is that you want to get across " (pp. 222). These strategies made teachers realise that undertaking research and then writing about it implies extensive reading: "I think before writing we have to read more so that at the end we don't have problems dealing with the whole sense of our articles" (Sonya).

Coping with editors' feedback.'Editors' feedback led teacher-researchers to write several drafts. This was done to ensure papers would have a discernable line of development, an adequate analytical framework, and a useful set of ideas for potential readers of the whole piece.

When talking about his experience as an editor, Benson (2000) also notes that those writers who persist, who re-work their articles and attempt to grapple with the comments are the ones who finally get their work published. All the way through the PROFILE Journal editing process I could see that as teachers evaluated the content and intention of editors' feedback, they realised that it may take two or three drafts to improve their chances of being published. This was confirmed later on when some teachers reflected upon their writing experience: "It was necessary to write and rewrite, revise many times" (Sandra).

I also noticed that when authors got feedback from the tutors and revised their writing, they were able to take a different perspective and to draw on their understandings about research and language use. This could be done by paying attention to language use or style as well as to the parameters for writing research reports. "It was good to have feedback from the professors. Melba helped me with the research design and Tamsin Mitchell with the editing of the article" (Sandra). Now, given the fact that writing implies accurate and appropriate language use, most teachers valued the fact that they could get assistance in it. As we can read in the following testimonies, teachers admitted it was of paramount importance to get support in language use: "A native speaker backed my article writing up by giving me suggestions and very useful corrections to improve the final paper" (Luz Marina). "It was good to have the teacher who helped us a lot in our process of getting ready not only with the article but also with our English" (Diana). "The teacher guided me to do the project and correct the mistakes" (Margarita Rojas).

In this section I have highlighted the parameters I set out to lead and keep track of the writing process. When defining and describing them I have also referred to some obstacles we confronted as well as to the paths we went along to accomplish the writing goal. In the following section I pinpoint teachers' perceptions regarding problems they had to take control of throughout the articles' writing process.

DEFEATING THE ENEMY: HOW WERE DIFFICULTIES OVERCOME?

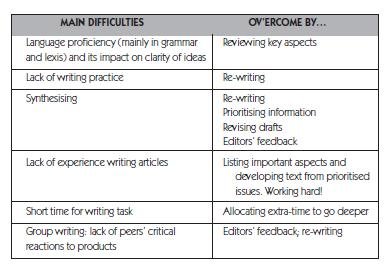

The process of writing an article allows us to construct and generate meanings for ourselves as well as for others. However, as teachers admitted in the survey given to them one or two years after their articles were published, this was not an easy job. During the writing of the rough draft, when teachers endeavoured to put things on paper and focused on constructing meaning, several obstacles appeared. Fortunately, they were overcome through applying their own strategies or some suggested by the tutors.

In the table above we can see that one of their main obstacles found was in the area of language proficiency. Teachers showed they had difficulties in vocabulary "to look for the most appropriate words to express ideas": Luz Marina); to organise understandable discourse ("to write in such a way that all the ideas were clearly and completely presented": Claudia) or to create a grammatically correct text ("I had some trouble constructing sentences. In general, grammar difficulties": Sonia). Despite those difficulties, the editing process was seen as an opportunity to revise language patterns, to learn new

Table 1. Main difficulties and solutions identified by teacher researchers as expressed in a survey (see appendix 1)

ones or to revitalize fluency that seemed to have vanished as a result of lack of practice.

Academic writing seems to decrease as teachers get immersed in the school routines. As all they are required to write is mainly connected to lesson planning, testing, class instructions, and syllabus design, lack of practice was a major constraint teachers faced. This was explained by some teachers as follows: "I&pos;ve never written an article "(Magda); "I didn't know how to write a project... academic writing "(Margarita Rojas); "Secondary teachers do not practice writing because the environment does not require it... I have lost this practice" (Sonia). The fact that teachers had not written academic papers recently was manifested in their fear to write, the difficulty of summarising ideas and the feeling they did not have enough time to complete the task. Hence, tutors and peers' feedback as well as reading of academic papers helped us achieve our goal.

It should also be noticed that as some teachers developed collaborative research projects, this implied team writing. Nonetheless, this was a constraint for some groups whose heterogeneity did not guarantee richer product construction:

"I didn't participate in the writing of the article because I have many difficulties to write... I worked as an assistant in the group "(Víctor).

In this particular case, brainstorming, peer feedback, critical views, and constant dialogue were emphasised as a means to foster writing. Encouraging heterogeneous groups to write their articles despite the difficulties they had was a vehicle to help the less proficient teachers for, as pointed out by Christensen and Atweh (1998), writing collaboratively can assist in professional development of less experienced members of the team by providing them with an opportunity to develop their skills and confidence in writing.

In cases when a group member was more proficient in the language, peers' critical reactions to partial or final products was scarce as most group members relied on the leader's capabilities and adopted a neutral or passive role in the editing process:

"I think writing a paper in a group is really difficult. It was difficult to have opinions from my partners, they said it is OK, and I wanted them to give me feedback but they didn't." (Sandra).

As can be seen in this statement, lack of active group members' involvement generated a feeling of frustration as interaction did not play a paramount role in the text construction. This can make us foresee arrangements during the writing process so that, as suggested by Christensen and Atweh (ibid), writing teams negotiate roles in order to ensure full and equal collaboration.

Despite the difficulties we had, it should be stressed that readiness to taking the risk to write and re-write the articles, commitment to end up with coherent and complete versions, and the enthusiasm to get them published were steering factors to reaching our targets. In the following section I will discuss some ideas concerning gains teachers identified as a result of the article writing experience.

WHAT A PAIN! BUT WITH GOOD GAINS!

As explained throughout this paper, the writing of the articles published in the PROFILE Journal was the result of classroom research. Though participants were novice researchers, they recognised the importance of research:

"I am using action research as a means to analyse and solve problems in my classroom" (Luz Marina). As can be seen, classroom research became of particular interest to teachers, because it is connected to their own experiences: "I enjoyed working on the research project. It helped a lot in my activities at school". In the same line of thought, and similar to what Burton and Mickan found in an in-service programme for language teachers (1993), I could observe that although the writers were initially hesitant about their ability to write in what they viewed as an academic genre, they found that the writing process itself became part of the clarification of their ideas as well as the setting of further action and professional renewal goals. For example, when specifying the gains from the writing experience Sonya stated: "I noticed that researching is very important for teachers... we can find solutions to our classroom problems facing them through research focused on it".

As already mentioned, on the subject of language development, teachers valued the contribution writing had on English proficiency, particularly in the areas of writing and vocabulary: "I learnt new vocabulary and checked words I was no longer using" (Luz Marina); ´I improved my English and learned different tools to use in the classroom¡ (Margarita Rojas).

With regard to the value of publishing, I agree with Benson's conclusion: "Publishing is a way for members of the academic community to share ideas and possibly contribute something to the world's store of knowledge. To publish is to engage in a dialogue with unseen and often unknown others" (2000, p. 33). This is backed up by Dianas' reflection: "I had the opportunity of sharing different experiences with other teachers, and I could learn different things about teaching English in different levels". However, and as I said before, teachers often feel they have nothing or very little to say. Likewise, they underestimate their production as they sense that what they have written is not new or valuable. This might be due to the fact that they are influenced by a top-down tradition which associates professional knowledge with that coming from outsiders, mainly linguists, university professors and researchers who are not necessarily based at schools or who have little knowledge of what happens there. In our case, as teachers undertook academic writing activities self-esteem seemed to increase. This was probably connected to the fact that they recognised they had gained experiences as well as stronger and more integrated perceptions of their teaching job: the teacher as a practitioner, as a researcher and as a writer. "In my professional career I felt stronger, with more skills developed" (Sonya).

In the same line of thought, writing about the classroom research experience generated the need for on-going teacher preparation. As a result, some teachers felt ready to carry out other studies to strengthen their professional competencies. Sandra, who then started a master's programme in English language teaching, illustrates this gain when she asserts: &quaot;It is good to have a published article because it shows that I have done research before. This experience is really important for my CV"

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Publishing as part of research projects is often taken for granted by researchers, teacher educators and advocates or classroom research methodologies. This article has described the way the writing process has been guided in TPDs, the achievements of the experience, the criteria borne in mind for task completion, the problems teacher researchers faced, and the tools they used to overcome difficulties. Nonetheless, there are some implications we may need to consider.

Writing and publishing is seen as an essential and central process in classroom research projects. Research is valuable if it is disseminated and this can be done through informal or formal presentations. The former can take place at school or in teachers' conversations, whereas the later is possible through participation in varied events such as seminars, workshops or conferences. Another alternative is the publication of research processes and findings in newsletters, conferences' proceedings, journals or books. However, this last option does not have a long tradition in our ELT community.

Teacher educators, evaluation agencies and research communities often refer to students' low writing proficiency and this is in turn associated with teachers' competencies. Likewise, TDPs do not often insist on written production as a means to foster language development or to enhance networking through reading peers' papers. This could be somehow explained by the fact that methodology updating, grammar and conversation skills are more prioritised in those courses.

For university teachers and teacher educators, writing essays, reports and academic papers has become a common practice. We argue this is a way to merge the practical dilemmas and the conceptual frameworks we validate or construct day by day. However, we cannot forget that writing is a skill school teachers should also practise in in-service programmes not only as a means to help them develop skills for social communication or for paper work required in their teaching job, but also as a strategy to register and exchange innovations, reflections or results they gather while teaching the language.

Composing every single sentence demands close scrutiny of each assumption and idea. Throughout my participation in teacher development programmes and my experience editing the PROFILE Journal, I have confirmed that writing is a life-long process that needs constant practice. In view of this, I believe that in order to enhance teachers' writing skills, teacher education curricula should incorporate a writing module either as part of a language development strand or as part of research projects' writing. This component could be enriched by reading professional articles or books that respond to teachers' common concerns, immediate needs, or current issues on education and methodology. These sources can provide both input in given areas and familiarise practitioners with different styles used in publications.

In most in-service programmes, writing commences late in the project and has the function of reporting on it. Writing early in the life of a project can make teachers see the task as a progressive activity rather than a tiring duty that brings stress when the final report has to be submitted. This way, the writing process becomes "useful or building the skill of critical reflection" (Christensen and Atweh: 1998, pp. 330).

Lastly, it should be remembered that sharing our own ideas with others can be beneficial in many obvious ways. As noted by Wallace (1998), sometimes, the mere necessity of having to articulate our ideas to an audience canhelp us to develop them in ways that might not otherwise have happened. The experience I have described here made teacher-writers more familiar with the process of writing for a professional audience and more at ease with reading more widely (Burton and Mickan: 1993). It would then be relevant to explore to what extent teacher-researchers as writers have engaged in or continued to read and write professional documents since participating in the in-service programme they studied at the University. Likewise, further actions could focus on exploring to what extent teachers' publications reach the academic communities they are intended for and generate reflections, debates, networking or some sort of communication.

REFERENCES

- Christensen, C. and Atweh, B. (1998)."Collaborative Writing in Participatory Action Research". In Atweh, B., Kemmis, S. and Weeks, P. (eds.) (1998). Action Research in Practice. London: Routledge.

- Benson, M. J. (2000). Writing an Academic Article: An Editor Writes... Forum English Teaching, Vol. 32, 2, pp. 33-35.

- Burton, J. and Mickan, P. (1993). Teachers" classroom research: rhetoric and reality. Teachers Develop Teachers Research. Papers on classroom research and teacher development. Oxford: Heinemann.

- Cárdenas, M. L. (2000). Action Research by English Teachers: An Option to Make Classroom Research Possible. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal. Vol. 2, 1. pp. 15-26, Bogotá: Universidad Distrital.

- Merriam, S. B. 1988. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- PROFILE. Issues 1, 2, 3. (2000, 2001, 2002). Bogotá: Foreign Languages Department, Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- Torres, G. e Isaza, L. (2000). Evaluación de los Programas de Formación Permanente de Docentes realizados en Bogotá entre 1996 y 2000. Bogotá: IDEP - CEE.

- Wallace, M. (1998) Action Research for Language Teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

NOTAS

- The PROFILE Journal is an annual publication. It is mainly concerned with sharing the results of classroom research projects undertaken by school teachers while taking part in professional development programmes in the Foreign Languages Department at Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogotá.

- A research project funded by the Research Division of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia in Bogotá (DIB) is currently examining the characteristics of teacher research (topics, methods, origins of teachers' inquiries), teachers' views about the effect or use of their research activity in their teaching practices and the impact research findings have had at schools.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.