DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n2.10610Publicado:

2016-07-18Número:

Vol 18, No 2 (2016) July-DecemberSección:

Artículos de InvestigaciónFostering EFL learners´ literacies through local inquiry in a multimodal experience

Fomentando literacidades de estudiantes de inglés a través de investigaciones locales en una experiencia multimodal

Palabras clave:

indagación en el salón de clase, pedagogías de comunidad, aprendizaje de lengua extranjera, literacidades multimodales (es).Palabras clave:

Community based pedagogies, classroom inquiry, multimodal literacies, EFL learning. (en).Descargas

Referencias

Blattner, G. & Melissa Fiori (2011). Virtual Social Network Communities: An Investigation of Language Learners’ Development of Sociopragmatic Awareness and Multiliteracy Skills. CALICO Journal, 29(1), p-p 24-43.

Burns, A. (2001). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clavijo, A. (2015a). Implementing Community Based Pedagogies with Teachers in Colombia to enhance the EFL curriculum. En Perales, M. y Méndez, M. (Eds.). Experiencias de docencia e investigación en lenguas extranjeras. pp. 31-43. Chetumal, México: Editorial Universidad Quintana Roo.

Clavijo, A. (2015b). Research tendencies in the teaching of English as a foreign language. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. Vol. 17 No.1. pp. 5-10.

Dewey, J., (1990). The school and society: And, the child and the curriculum. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Dewey, J. (1997). Experience and education. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum.

Garcia, O (2009) Education, Multilingualism and Translanguaging in the 21st Century. Chapter 8 in Social Justice through Multilingual Education. Multilingual Matters. USA. British Library

Haverback, H. (2009). Facebook: Uncharted territory in a reading education classroom. Reading Today. Vol. 27, No. 2. (October 2009) Key: citeulike:6130838

Hubbard, & Miller (1999) Living the Questions: A Guide for Teacher-Researchers. US: Stenhouse Publishers

Johnston, R. & J. Davis. (2008). Negotiating the dilemmas of community-based learning in teacher education. Teaching Education. 19:4, 351-360

Kress, G. R. (2003). Literacy in the new media age. London, UK: Routledge.

Kozinets, R.V. (2010). Netnography: Doing ethnographic research online. U.S.: Sage Publications.

Kretzmann, J. P., & McKnight, J. L. (1993). Building Communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community’s assets. Chicago, IL: ACTA Publications. Retrieved from: http://www.abcdinstitute.org/publications/downloadable/

Majid, A.H.A., Stapa, H.S. & Keong, C.Y. (2012). Scaffolding through the blended approach: Improving the writing process and performance using Facebook. American Journal of Social Issues and Humanities. 2(5), 336-342.

Mills, K. (2011). The multiliteracies classroom. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Medina, R.A, Ramirez, L. M., & Clavijo, A. (2015). Reading the community critically in the digital age: a multiliteracies approach. In P. Chamness Miller., Mantero. M. & Hendo. H (Eds). ISLS Readings in Language Studies: Vol. 5. Pp.45-66. Grandville, MI: International Society for Language Studies

Murrell, P. C. (2001). The community teacher: A new framework for effective urban teaching. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Norizan Abdul Razak1, Murad Saeed1 & Zulkifli Ahmad1, Adopting Social Networking Sites (SNSs) as Interactive Communities among English Foreign Language (EFL) Learners in Writing: Opportunities and Challenges. English Language Teaching. Vol. 6 No.11. 187-198

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity and educational change. Harlow, England: Longman.

Quintero, L. (2008). Blogging: A way to foster EFL writing. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. Vol.10, 7-49.

Reyes, N. (2012). Engaging EFL learners in community based activities to develop their literacy processes in EFL. Unpublished master thesis. Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá.

Rincon, J. (2014). Fostering students’ inquiry skills through community based pedagogies. Unpublished master thesis. Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá.

Scheter, S., Solomon, P. & Kittmer, L. (2003). Integrating Teacher Education in a Community Situated School Agenda. In Scheter, S. & Cummins, J. (Eds.) Multilingual Education in Practice: Using diversity as a resource. Porstmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Sharkey, J., (2012). Community-based pedagogies and literacies in language Teacher Education: Promising Beginnings, Intriguing Challenges. Retrieved from: http://aprendeenlinea.udea.edu.co/revistas/index.php/ikala/article/viewFile/11519/10493 2012 Ikala.

Shih, R.C. (2011). Can Web 2.0 assist college students in learning English writing?. Integrating Facebook and peer assessment with blended learning. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. 27(5), 829.845.

Short, K. G. (2009). Inquiry as stance on curriculum. In Taking the PYP forward. Woodbridge, UK: John Catt Educational Ltd.

Somerville, M. (2010). A place pedagogy for ‘global contemporaneity’. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 42, page numbers. doi:10.1111/j.1469-5812.2008.00423.x

Warschawer M, & Kern R (Ed). (2000). An Electronic Literacy Approach to Network-Based Language Teaching Network-Based Language Teaching: Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic inquiry: Towards a socio-cultural practice and theory of education. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wells, G., & Claxton, G. (2002). Learning for life in the 21st century: Sociocultural perspectives on the future of education. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Whitin, P., & Whitin, D. J. (1997). Inquiry at the window: Pursuing the wonders of learners. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

RESEARCH ARTICLES

Fostering EFL learners' literacies through local inquiry in a multimodal experience

Fomentando literacidades de estudiantes de inglés a través de investigaciones locales en una experiencia multimodal

July Andrea Rincón1 Amparo Clavijo Olarte2

1 IED El Rodeo. Secretaria de Educación Distrital, Bogotá, Colombia. julyrincon@gmail.com

2 Universidad Distrital Francisco Joséde Caldas, Bogotá, Colombia. aclavijoolarte@gmail.com

Citation/ Para citar este artículo: Rincón J. & Clavijo-Olarte A. (2016). Fostering EFL learners' literacies through local inquiry in a multimodal experience. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 18(2), pp. 67-82.

Received: 23-June-2015 / Accepted: 05-July-2016

Abstract

Addressing students' social reality through the exploration of community inquiries in the English language class can create learning environments for developing students' language and literacies. This paper addresses the ways in which community inquiries create opportunities for students to explore social and cultural issues in their neighborhoods using multimodality. It discusses the role community inquiries play in the development of literacy practices of a group of 10th graders in their EFL class. This descriptive qualitative project carried out at a public institution in the south of Bogotá, Colombia involved 40 participants. The goal of the project was to transform the way students relate to the community in order to create local knowledge. Data was collected through videotape recordings of students' presentations, teacher's journal, students' interactions on Facebook, and students' blogs over a two-year period. The findings reveal that teachers and students enacted a critical pedagogy through an inquiry curriculum that explored community issues and allowed participants to become inquirers of their own realities. Students' language learning was evident in multimodal texts in English in their blogs, in the use of EFL in their oral presentations, and in their comments in response to peers on Facebook and their blogs.

Keywords: classroom inquiry, community based pedagogies, EFL learning, multimodal literacies.

Resumen

Abordar la realidad social de los estudiantes a través de la exploración de investigaciones en su comunidad en la clase de inglés permite crear ambientes de aprendizaje para desarrollar múltiples prácticas de lectura y escritura. Este artículo aborda la pregunta de quéformas las indagaciones sobre la comunidad crean oportunidades para que los estudiantes exploren aspectos sociales y culturales de sus barrios usando la multimodalidad. También discute el rol que las investigaciones de comunidad juegan en el desarrollo de prácticas de lectura y escritura de un grupo de estudiantes de grado 10 en su clase de inglés como lengua extranjera. Este proyecto es descriptivo y cualitativo y fue desarrollado en una institución pública en el sur de Bogotá, Colombia e involucró 40 participantes. La meta del proyecto fue transformar la manera como los estudiantes se relacionaron con la comunidad para crear conocimiento local. La información fue recolectada a través de grabaciones de las presentaciones de los estudiantes, el diario del profesor, las interacciones de los estudiantes en Facebook y el blog de los estudiantes en un periodo de dos años. Los hallazgos revelan que los profesores y los estudiantes promulgaron una pedagogía crítica a través de un currículo basado en indagación que explora asuntos de la comunidad y permite que los participantes se conviertan en investigadores de sus propias realidades. El aprendizaje de lengua extranjera de los estudiantes fue evidente en los textos multimodales en inglés, en sus blogs, y en el uso del inglés, en presentaciones orales y en sus respuestas y comentarios a sus compañeros en Facebook y en el blog.

Palabras clave: indagación en el salón de clase, pedagogías de comunidad, aprendizaje de lengua extranjera, literacidades multimodales.

Introduction

This qualitative study on community-based pedagogies (CBP) engaged students in rich schooling experiences as a way to reconcile the curriculum with the real life of students within their communities (Freire, 2000). It aimed at answering the research question related to the ways in which community inquiries create opportunities for students to explore social and cultural issues in their neighborhoods using multimodality. A group of 40 tenth-grade students from a public school in the southeast of Bogotáparticipated in the three-year project.

The decision of using an inquiry perspective in the EFL classroom opened a range of possibilities for students to collect and represent information by interacting with socially constructed tools or resources. Within and Within (1997) claim that:

when teachers grant [students] the responsibility to look closely, they also grant them the right to raise questions about what they see, the right to solve the problems they encounter, and the right to be empowered by the fruits of their struggles. (p.10)

Images, videos, music, and technology devices became the means students used to present a multimodal vision of literacy practices. These practices mediated by technology constituted a way to break with the bidirectional dynamic between teacher and learner and expand to a broader social interaction for building understanding with the other (Quintero, 2008).

During a period of three years, the school in which this intervention took place promoted the education of students with an emphasis on research. The pedagogical model of the school, based on socio-critical pedagogy for the development of research, science, and technology towards the benefit of the community represented an opportunity to transform the grammar based, mono-modal EFL teaching approach to a more participatory action research experience. The emphasis on inquiry in the pedagogical model of the school created a space to transform the focus on studying language grammar in the EFL class to inspiring students towards the inquiry process. Short (2009) claims that "once we explore inquiry as a natural learning, then we can engage in the difficult task of creating learning environments that immerse learners in these processes, rather than in how they should learn" (p. 13). The research spirit the school promotes represents an opportunity to engage students in meaningful use of the language by including the community and socio-critical pedagogies as key trends in the pedagogical model of the school. Observations of the texts and approaches of the curriculum display the disconnect that exists among the syllabus and real life of students. Implementing content-based instruction that integrates content, local contexts, and language learning experiences through community inquiries with school students became an alternative for both inquiry and language learning (Clavijo, 2015b).

As researchers and educators of public institutions which look into fostering critical thinking processes in students, we find the inclusion of community-based pedagogies in the EFL curriculum a positive experience for students' learning. We strongly believe that the inquiries students make of their own contexts bring meaningful thinking processes to the classroom. As community teachers, we find it both satisfying and challenging instructing a diverse group of students whose educational needs go beyond a linguistic focus or preparation of an exam. There is social engagement with students in situations of displacement (due to the internal war in Colombia) or whose socio-economic backgrounds are vulnerable. The problems students bring into the classroom represent an opportunity to reconcile the school with the real needs of society. Students' communities are places full of inspiration; if they are properly worked into the EFL classroom they can provide language practices that give students a voice and the power to be critical actors of their own realities.

Literature Review

This study is informed by local studies on community-based pedagogies (Clavijo, 2015a; Medina, Ramirez, & Clavijo, 2015; Rincón, 2014; Reyes, 2012; Sharkey, 2012), sociocritical theories on language teacher education (Johnston & Davis, 2008), critical pedagogy perspectives from (Freire, 2000), inquiry curriculum by Dewey (1990, 1997), Moll (1994) concept of students' funds of knowledge, and Murrell's (2001) contribution on the role of the community teacher. An inquiry perspective in the teaching and learning of language is supported by the work of Whitin and Whitin (1997), Cochran- Smith and Lytle (2009) by illustrating inquiry as a stance, and Wells and Claxton (2002) explaining inquiry as an orientation for learning and teaching. Finally, the contributions from Mills (2011), Kress (2003), Warschauer and Kern (2000), and Norton (2000) help us explain how multimodality and technology can be used in EFL learning.

Community-based Pedagogies, Curriculum and Pedagogy

Community-based pedagogies are outside school practices, life experiences, and assets that learners and teachers (who want to have a deeper understanding of the local places in which their students interact) bring into the classroom in order to enlighten class dynamics and curriculum constructs. In the context of EFL learning, outside school practices, elements, symbols, people, and situations that students and teachers identify during a process of joint inquiry become both theory and inspiring material for teacher researchers, especially in this generation of meaningful and critical literacy practices with students.

Sharkey (2012) define community-based pedagogies as "curriculum and practices that reflect knowledge and appreciation of the communities in which schools are located and students and their families inhabit" (p. 7). These authors carried out research in the United States and Colombia in which in-service teachers engaged in the investigation and implementation of community-based pedagogies with their students in foreign language classrooms. One of the student teachesr involved in this study provided critical insight towards her experience of including CBP into the classroom. She asserts that "curriculum can come from the interaction between student, teachers and experiences; it does not have to come from a textbook or in a box of materials from the district office" (p. 8).

Similarly, Rincon's (2014) CBP study with tenthgrade students in a public school in Bogotáis an example of a community teacher and her leadership and commitment to bettering the lives of lowincome students and families. Learning how to study the communities as rich resources for curriculum and teaching provided her with the tools to explore social and cultural issues of the neighborhood with her tenth-grade students. Learning through local inquiries was an ideal reason for students to share insights about local concerns through Facebook forums and an online blog in her classroom project.

Additionally, Reyes (2012) carried out a community project with at-risk elementary school students in an after school program and with college students to promote awareness of community resources in language education in Bogotá. She integrated the funds of knowledge that students brought from home as important resources for curriculum building and highlighted the importance of integrating linguistic and cultural sources from the community into the classroom. During her experience teaching elementary school children from 6-9 years of age, she was surprised that the only place students were familiar with was their close neighborhood and did not know any other place within the city of Bogotá. They only knew their barrio La Gaitana and its surroundings. To do a more contextualized teaching, she took time to map the neighborhood, take pictures of the community where the students lived, and use the pictures as material to create a meaningful curriculum and to teach students. She intended to become a community urban teacher. As a university teacher of English, she promotes taking action on local issues in communities that have urgent needs to be solved. Thus, students explore social issues in the community in order to connect their EFL class with the necessities and requirements of their fields of knowledge.

Regarding the mutual participation that needs to be granted among the community and the school, Whitin and Whitin (1997) state that "one of the benefits of working in a community is that it is a collaborative resource" (p. 7). When thinking of bridging the gap between the school and students' communities, teachers bear the responsibility of becoming experts on the research of community dynamics. Teachers initiate a process of joint inquiry among parents, important people in students' communities, teachers, and students themselves. The allies achieved through the formation of this group assure a critical reading of spaces, experiences, and situations in order to inform a more human and inclusive curriculum.

Concerning the professional development of teachers, Murell (2001) asserts that "the field experiences [that teachers and students acquire from the interaction with] community settings provide multiple opportunities to acquire and apply the range of situated [and formal] knowledge required for successful practice" (p. 6). When including students' context in their school programs, their learning practices become more meaningful; the top-down vision of the teacher and learner is shifted by a horizontal view in which teachers and learners feed the curriculum together through their explorations.

In current practice in schools and hearing colleagues in the field of EFL, when administrators develop curriculum, the school involves the knowledge and experience of teachers and authorities in the main disciplines of thought. However, the family, parents, community, and students do not participate in the process. Neither their experiences nor their surroundings are part of it. The banking model explained by Freire (2000) illustrates how teachers are the knowledgeable entities filling students with what they consider useful; students are empty vessels waiting to be filled. Freire (2000) gives an account of research with a group of peasants participating in a reading circle. These peasants were supposed to engage in dialogue together; however:

They call themselves ignorant and say the 'professor' is the one who has knowledge and to whom they should listen… almost never do they realize that they, too, 'know things' they have learned in their relations with the world and with other women and men. (p. 63)

Freire illustrates through this example how the criteria imposed on students results in submission of the learner and other entities around the construction of knowledge. However, theorists who praise joint participation in curriculum construction support Freire's theory. Murrell (2001) states that the school should work humbly in collaboration with parents and the community doing inquiry together in order to nurture learning and teaching practices that benefits students by creating meaningful practices that involve their reality, experiences, and communities. In the words of Dewey (1990), "we must conceive [the assets of the outside context] in their social significance… through which the school itself shall be made a genuine form of active community life, instead of a place set apart in which to learn lessons" (p. 14).

Community-based Pedagogies within an Inquiry Perspective

By including the recognition of the community, students become critical readers of their own contexts. They develop a sense of belonging and, as a product of this process, inquiry and academic skills. However, the process of inquiry must start through guidance teachers provide to learners. Inquiry starts by close observation of elements and situations the teacher invites students to explore. For Short (2009), "without invitation… we may not feel the courage to pursue [the] uncertainties or tensions [of the outer world]; invitation beckons us to feel some safety in taking the risk to pursue those possibilities by thinking with others" (p. 12). The result of inquiry generates curiosity for further information.

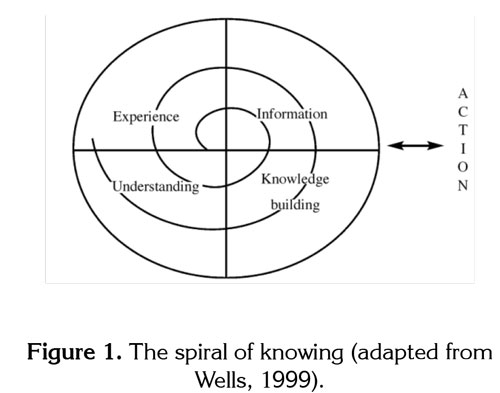

Wells and Claxton (2002) discusses an investigation conducted with multicultural students in a science class. In this research, students looked closely for the first time at the birthing process of a butterfly. Students were engaged in the posing of questions and came up with their own answers. Wells states that the problem remains of teachers wanting students to provide pre-established answers or, to put it in his words, "the solution that is culturally accepted" (p. 149). In his model of the 'spiral of knowledge,' Wells (1999) proposes an alternative for inquiry: take into account students' experiences and backgrounds as key information for knowledge building. The model is provided and explained below.

In the spiral, each cycle starts with the understanding of individual past experiences that participants bring into the problem situation. This is new information made available by the teacher, text, or situation and activity. Wells and Claxton (2002) consider that for this new information to lead to enhanced understanding, it must be individually appropriated and transformed; this occurs through collaborative knowledge building. This happens through action on the object that is the focus of the joint activity and through dialogue in which participants make sense of and evaluate new information (Wells, 2008), relate it to what they currently believe, and use it to guide action and enhance understanding of the matter at issue.

The study with multicultural students sheds light on the need for curriculum construction in which inquiry and student experience provoke questions that students answer through a process of discovery. Schools should avoid the historical tradition of preestablished answers that students must recite. Wells (2002) believes that when students are "affectively and intellectually engaged…[the] problems have no single answer and there is not an all knowing authority" (p. 199). There is a need for joint research outside the classroom in which the school, parents, students, and society participate. The research should aim to create more conscious citizens and responsible individuals.

Community-based Pedagogy and Teacher Education

The implementation of community-based pedagogies in schools has implications for teacher education. CBP entails teachers organizing the curriculum content around social and cultural concerns of the local context, involving students and families in local inquiry, and discovering linguistic assets from the community. Scheter, Solomon, and Kittmer (2003) highlight the importance of preparing teachers for working in multiethnic, multilingual urban school environments characterized by transition and flux and invite preservice teacher education programs to incorporate responsive orientations and strategies. Preservice and practicing teachers in Colombian classrooms in big cities where we receive students from diverse contexts will benefit from a community-oriented approach to teacher education. Similarly, Murrell, (2001) defines the community teacher as one who "possesses contextualized knowledge of the culture, community, and identity of the children and families he/she serves and draws on this knowledge to create core teaching practices necessary for effectiveness in diverse settings" (p. 51).

Johnston and Davis (2008) draw on a collaborative approach to community based learning (CBL) with pre-service teachers and established community linkages to foster L2 learning. CBL guides teachers to use teaching principles that establish that "students learn best when: learning connects strongly with communities and practice beyond the classroom [by interacting with] local and broader communities and community practices" (p. 352). Most of the projects carried out by pre-service teachers encouraged them to understand children as "active and informed community agents" (p. 352). The information gathered by teachers and students during community inquiries enriches the curriculum, making it more inclusive.

Multimodality and CBP

Multimodality generates endless opportunities in the EFL classroom for students to communicate. Most schools are still dominated by traditional writing practices that praise the use of paper in which merely linguistic productions are promoted. However, as stated by Mills (2011), "the modes are the starting point to develop new 'grammars' or a 'metalanguage' for a broader range of textual elements than linguistics (written words) alone" (p. 54). During a study conducted with immigrant ELL students, Somerville (2010) achieved a sense of understanding of the value local knowledge has on the thinking processes of students in EFL. Students shared stories and assets identified through a process of inquiry conducted in their communities with the use of multimodal tools. The products of students' inquiries were displayed in videos, music, and images accompanied by texts created by students. Somerville (2010) highlights the double literacy acquired by students in the use of EFL and in multimodality for communicative purposes.

Quintero's (2008) local study in an EFL classroom in Colombia investigated a group of first year university students' blog interactions in EFL. Her teaching aimed at promoting writing and communication skills in EFL supported by blogs. She found that a "community of bloggers" emerged when writing about topics of personal and academic interest cooperatively. Her findings suggest that EFL writing is greatly developed when students feel part of a community they interact with, share similar interests and language learning goals with, and when that writing is mediated by technology. Her results also show that by writing in blogs, students developed literacy practices and had the possibility to portray their selves through the written pieces they posted (Quintero, 2008). These findings support Somerville's (2010) statement on the double literacies acquired when using EFL and multimodality.

Another study in which computer mediated technologies were used in the development of literacy practices is the 'strawberry project' reported by Warschauer (2000). This project provides ideas of how community pedagogies and technology work together to empower students to think critically and adopt new literacy practices that come with a sense of belonging. In this project, a group of students in Oxnard, California engaged in a project where their context was the main topic of discussion. The local strawberry field was one community place the students analyzed. As this industry represented an economical source for students' families, students were engaged in the project. They interviewed workers and described the situations workers were confronting. Students created PowerPoint presentations that were shared through the web to classmates (Warschauer, 2000). This work influenced the present study as the implementation of tasks provided to students give ideas in the construction and planning of activities to implement in this research. It also evidences that community-based pedagogies and multimodalities represent new alternatives to achieve meaningful practices for students, especially in communication and self-expression.

Using Social Networks as Tools for Communication in Foreign Language Learning

Norton (2000) considers that students limit their participation in the classroom because of the lack of domain in the second language. These students experience anxiety because there are strict norms of avoiding their mother tongue when intending to express their opinions, which results in silence in the classroom and little investment in the learning of a language. This can be the case of many EFL students in public and private schools in Colombia. Thus, social networking becomes a communication possibility in the foreign language.

In second and foreign language education, technology has become an important tool that, if integrated in the classroom, can open opportunities for learners' social interaction and self-expression. Considering that, the use of the Internet provides teachers and students possibilities to create social networking communities (SNCs) online, participating in social networking communities such as Facebook groups, forums, and blogs as safe interactive spaces can enrich the learning experience for foreign language learners.

In this regard, Blattner and Fiori (2011) investigated whether a social networking community (SNC) website such as Facebook can be exploited in the context of an intermediate foreign language class to promote competent, literate L2 learners. Their findings report that students were able to identify cultural elements in authentic conversations with participants in the Facebook group and integrated new ways to learn a foreign language. In the conversations in the Facebook forum, students were able to identify and use abbreviations and their meanings (e.g., the use of the @ symbol to express gender inclusivity). The authors concluded that by incorporating versatile Web 2.0 tools that enhance the quality of the classrooms, educators could exploit SNCs such as Facebook to create a dynamic learning environment, promote critical thinking, offer authentic L2 learning opportunities, and develop multiliteracy skills.

A study investigating the adoption of social networking sites (SNSs) with college students in EFL classes by Razak, Saeed, and Ahmad (2013) criticize traditional EFL classes that do not include collaboration and interaction in college writing classes. From an interactionist framework that views learning as an interactive social act, the authors investigated the challenges and opportunities of SNSs as learning environments in writing in English. They considered that SNSs as online communities of practice are rich learning environments for learners to practice English. Their study is supported by other studies that reveal that Facebook facilitates learners' writing process like Haverback (2009), Shih (2011), and Majid, Stapa, and Keong (2012). The data was collected from the interactional exchanges of learners in weekly writing activities and the responses to questions posted by the instructor. Their findings report evidences of the interactive nature of Facebook as a community of practice that permitted students to be actively involved in writing activities through collaboration, interaction and scaffolding writing in both sides; learner-learner and learner-instructor. Some challenges regarding technical Internet problems were reported.

In sum, the studies above mentioned present the integration of SNSs in foreign language teaching and learning as useful tools for learners to participate in authentic conversations with peers NSs or NNSs of English. The development of multiliteracy skills, contact with the target culture, and the process of scaffolding writing are some of the advantages for foreign language learners of English to be considered in the TEFL field.

Methodology

The present study relies upon the action research paradigm (Burns, 2001) to answer the following research question: In what ways do community inquiries create opportunities for students to explore social and cultural issues in their neighborhoods using multimodality? For Burns (2001), action research is a methodology that combines action and research where findings are put into practice. "It is a form of inquiry in which practitioners reflect systematically about their practice in order to obtain results that contribute to improve and build knowledge. It follows cyclical stages in which practitioners observe, reflect, revise, plan and act" (Burns, 2001, p. 33).

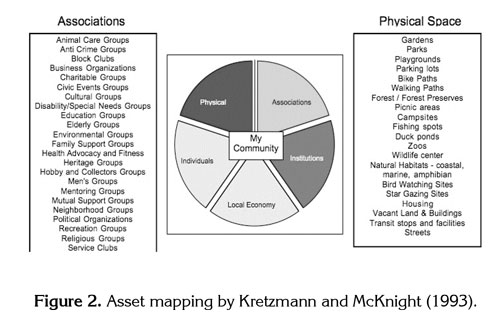

During the development of this study, the two researchers observed, planned, and executed three moments or cycles that started in May 2012 and ended in February 2014. The first moment was the mapping of the students' communities that included identifying five community assets as proposed by Kretzman and McKnight (1993): physical spaces, associations, people, institutions and local economy (see Figure 2 below). The second moment was characterized by students' initiation on inquiry to their communities. It implied deciding upon whom to interview, what questions to ask, and what permissions to ask for when taking pictures in public places among other things. The third moment focused on classroom presentations about community information collected and the materialization and display of students' findings in the blog.

Context and Participants

This research was carried out at a public school located in the south of Bogotáwith a student population in two branches of 1600 students in the morning and afternoon shifts. It is a small school recently re-built by the Distrital Secretary of Education. The school has been equipped with technological tools such as personal computers and internet connection, which facilitated the implementation of the study. The students come from low-income families as reported in the subsidized health system (SISBEN) and a few have suffered displacement due to internal war.

The population that participated in the study was a group of 40 tenth graders whose ages ranged from 14 to 15 years. The students belong to social strata 1 and 2—the two lowest socio-economic levels. The selection of the population was done by considering the group of students that needed to raise their low academic and disciplinary performance as a way to engage them in meaningful literacy practices that could help improve the situation students were going through.

Instruments

This study looked into fostering students' inquiry skills through the exploration of community-based pedagogies. Data were collected through videotape recordings of students' presentations, class debates, teacher's field notes, students' interactions on Facebook and students' blogs. The information was gathered in order to observe and document the process of inquiry with students (Hubbard & Miller, 1999).

We collected field notes from class sessions devoted to doing community mapping with students and students reporting inquiry results. Video tape recordings of class debates helped the researchers observe participants from a general and from a specific perspective and they served as an instrument to verify notes on a specific event to elucidate the data interpretation and analysis. Students' productions in this study were the multimodal representations accomplished by students during the final stage of the project and were shared on the blog. Students' blog entries provided the flesh of the data interpretation and analysis as they documented information regarding students' insights into their communities, processes of inquiry, and examples of language learning depicted in students' multimodal reports.

Data Analysis and Findings

Using the grounded approach, we began analysis by reading the data gathered from the students' blogs, video tape recordings of class debates, and the teacher's field notes. The data collection instruments were used to triangulate, validate, and verify the evidence to draw appropriate conclusions. ATLAS TI was useful to codify and organize data. We created a hermeneutic unit in which the teacher field notes, video tape transcriptions, and blog contributions in form of images and text were organized. We also used color-coding to search for patterns and themes, which were common and frequently seen in the different instruments. These themes turned into two categories that emerged as the process of data analysis developed namely: From inquiry to multimodality in CBP and Students' EFL learning through social networking.

The two categories illustrate three inquiry moments for intervention in the communities namely mapping, posing inquiry questions, and presenting findings. Within these moments, we found that students developed inquiry skills through observation and identification of assets, finding an issue, documenting the issue, and presenting findings and the multimodal way to represent their understanding of socio cultural issues in their communities. We also elucidated students' linguistic abilities in EFL writing (literal, descriptive, interpretive, and argumentative) in their Facebook and blog interactions. Through students' texts, we observed the use of both Spanish and English in their writing development in EFL. We call that process translanguaging which depicts a moment in students' language learning.

From inquiry to multimodality in CBP. This category explains the move between the moments, processes, and outcomes of students' community experiences. It also explains students' experiences by starting to question and identify issues and relevant aspects within their communities. Community mapping, community observations, photo and video analysis, class discussions, and the creation of questions guided students' inquiries. Murrell (2002) asserts that the context in which students' communities are framed possess a rich content of socio-cultural knowledge, community, and identity. Students interviewed important people in their communities to expand information on their findings and created multimodal reports. Finally, this category documents the outcomes of the three queries that guided students' inquiries in the EFL blog.

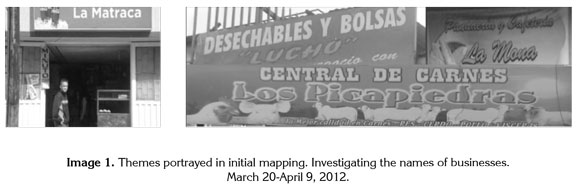

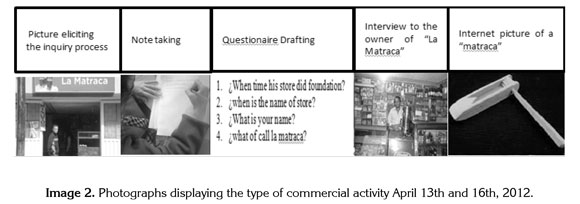

Observation and identification of assets. The images selected by students during the mapping illustrate the economic activities found in their communities.

Identification of an issue - question posing. Looking at the pictures collected during the mapping generated questions about the origin of the name of peoples' businesses, economic activity, street sellers, well-known people for the community, drug addiction, alcoholism, violence, bullying, abortion, prostitution, education needs, birth control, poverty, indifference, tolerance, religious views, pollution, and traffic.

Documentation of the issue. In this level, students used note taking, questionnaires, interviews, and internet search to document a problem. During the review of photographs, students identified and enlisted a series of characteristics of local businesses, social, and cultural issues.

In the previous sample, students wondered about the name given to the bakery and the location of "La Matraca" in Colombia; they spoke about the relation the name has with the type of commercial activity and the reasons for Santiago's3 father's migration from his city. Santiago shared with the class information related to the place where his father was born.

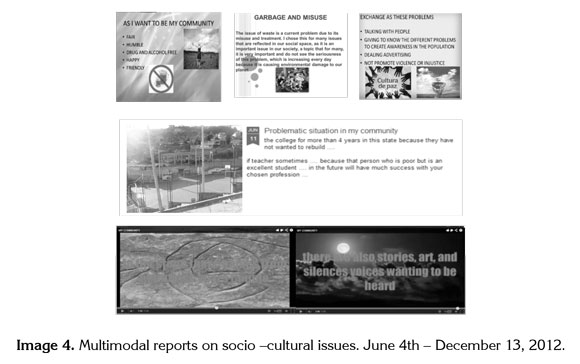

Presentation of findings. Students presented inquiry reports, PowerPoint presentations, videos, songs, and artistic creations to inform their audience (class) about the results of their inquiry. To prepare their report in English, they strategically drafted the responses obtained by business owners used the computer room to prepare the document, had the English teacher proofread their texts, and enriched 3 All names are pseudonyms. the document with pictures and internet images. Students submitted a full final report in the blog and commented on their peers' work.

Students' inquiries display four main groups of problems related to the environment, education needs, violence and youth addictions. Their participation in class debates and blog reactions revealed the impact of studying the community in students. The classroom and online discussions show their awareness of problems and their concerns about ways to find solutions.

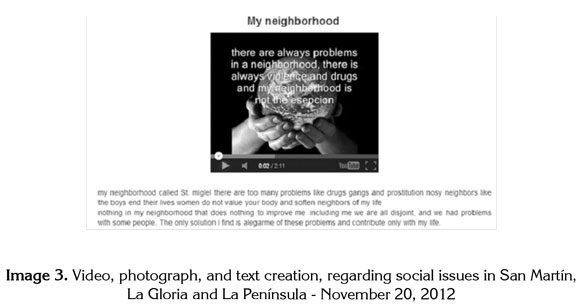

One of the students (Francisco) presented a well-documented, multimodal report of what happens in his community. He identified seven issues in two nearby barrios: "La Gloria and La Peninsula." Drugs, gossip, gangsters, insecurity, prostitution, poverty, and violence were the problems he identified and he writes about in his multimodal report (see Appendix 1).

Francisco had a strong personal impact from the results of the inquiry in his neighborhood. He decided to react towards the problems by composing a rap song, creating a video that encoded voice, narratives, and images. In the lyrics of his song, he expresses that "issues quickly spread as a disease in the country as children imitate what they see." In the sample provided above, he sees himself as part of the problem when saying "my neighborhood does nothing to improve me including…the only solution is alegarme [get away] of these problems and contribute only with my life". At the end, he composes a rap song in Spanish that invites people to reflect about what happens in society, but later he discusses it with his peers in the blog in English (see Appendix 1).

The inquiry that students did in their communities unfolded a wide variety of multimodal ways to represent their findings. This sets a linguistic precedent for students to attempt to develop better literal and descriptive EFL texts and in so doing to achieve the interpretive and analytical level of texts in EFL. The multimodality was fundamental in the development of language abilities due to the range of possibilities new media brought to the EFL classroom. Multimodality breaks with the monolingual EFL classrooms in which only written texts are used.

Students represented their understanding of social and cultural issues through slide presentations, song creations, stories, photo galleries, videos, scripted voiceovers, music, and video clips from the Internet to create their reflections. The following collage portrays the contributions uploaded to the EFL blog.

Before this pedagogical project started, the English classes showed students limited to a vision of literacy in which its meaning represented the ability to read and write (Barton, 1994). However, as the project developed, students used technology resources to achieve communication in the foreign language. This was the case of Francisco who used multiple modes to compose a rap song in reaction to the problems and cultural manifestations in his neighborhood (see Appendix 1). Although the rap is in Spanish as his mother tongue, he elaborates a full description of the topics treated in his song by using scripted texts in EFL, images, and videos. His rap represented an inspiration for three other students who composed songs about their communities by using different modes. The projects that Francisco, Santiago, and Carlos shared with the class shed light on the importance of promoting different literacy practices in the classroom.

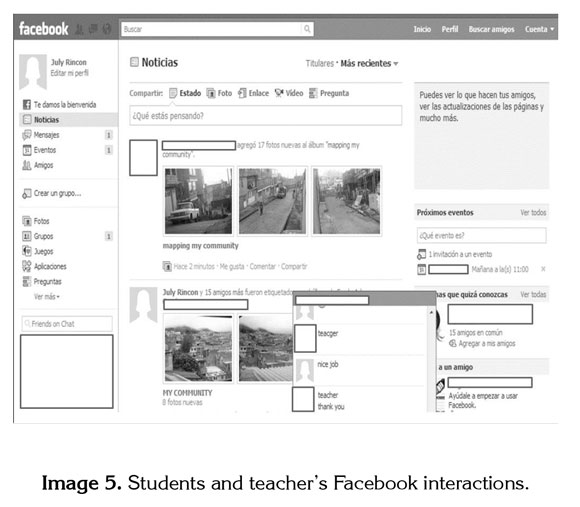

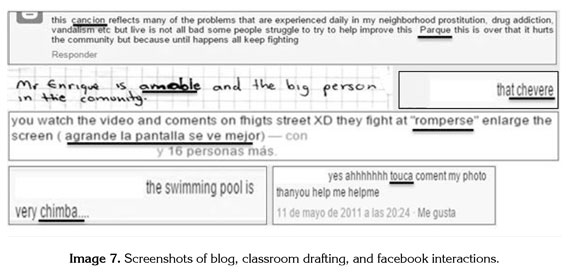

Students' EFL learning through social networking. The second category focuses on the language learning opportunities provided to students to communicate their ideas to peers in the social networks and the support given by the teacher to proofread students' writing. In addition, this category illustrates the use of both languages as linguistic resources available to them when reporting about their communities. On Facebook, students scaffolded each other's writing. This platform served as a means to solve questions, shared pictures, and welcome comments from students' parents and other community members.

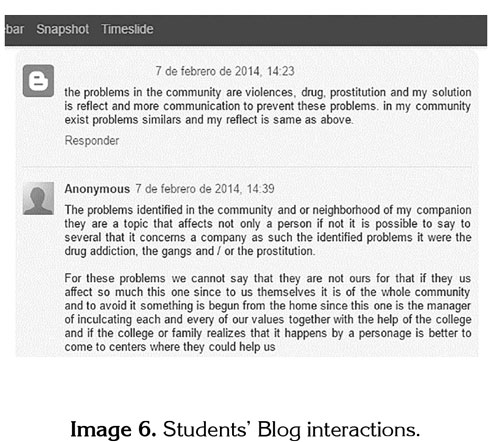

During the project, the teacher scaffolded students' writing by providing feedback to students' drafts before uploading their texts to the blog. Before uploading students' reflections and contributions to the blog, they wrote in class to receive guidance and have the teacher proofread their works. Students drafted their reflections on paper in class and worked on changes by using computers in the technology room; other students sent their written reflections through e-mail for correction. Although traces of grammar mistakes in English were present in the final version of their texts, their products made students feel more comfortable when writing in a foreign language. As in image 6, students who were always reluctant to learn English provided memorable works for the class. Students produced rap songs, reports, and descriptions of their neighborhoods.

Community contributions to the blog, Facebook, classroom compositions, and oral debates illustrated the linguistic resources that students used to convey meaning. Students' oral and written interventions combining the first and foreign language give an account of what García (2009) terms translanguaging. She defines such as "the act performed by bilinguals of accessing different linguistic features or various modes of what are described as autonomous languages, in order to maximize communicative potential" (p. 140). Common expressions within students' daily interactions in Spanish (romperse, chimba, toca) and unknown words in English (amable, grocerías) bridged the gap between language learning and self-expression.

The allowance of students' ways of languaging within the EFL class reveals a higher number of participants willing to express their opinions and with lower levels of anxiety. The contributions made in L1 engaged and contextualized other students who actively participated in both written and oral interactions. Insisting on the use of the academic standard within language learning environments may lead to linguistic insecurity and linguistic failure (García, 2009). The acceptance of the linguistic resources that students brought into the EFL classroom promoted communication and self-expression.

Teacher: What type of economic activity do they

develop?

Students: Ella sabe. (She knows)

Teacher: Come on Linda, participate

Student: No, no séteacher. Hmm persons…

roban cellulars y van y los venden

Sample 9. Transcription of first class debate.

From the analysis of the results represented in the two categories, we can conclude that the community was a space to develop inquiry skills that informed language practices and personal reflections displayed in multimodal ways. The problematic situations presented in the classroom in the form of questions resulted in the development of inquiry abilities that helped students observe, identify, document, and present outcomes in the EFL classroom. In terms of language development in EFL, documenting the issues, reporting the results, and communicating with others in social networks implied writing and rewriting their texts to achieve readable, comprehensible messages. The creation of documents, slide presentations, creative videos, and rap songs enriched with photographs, internet images, and music allowed the EFL class to be a multimodal classroom. Using social networks as platforms for communication was beneficial for the language learning process.

Conclusions

As teacher-researchers framed within the environment of public education, we discovered the school as an asset, its surroundings, and students' communities as spaces that offer remarkable opportunities for inquiry, information gathering, and transformation of curricular practices to make EFL classes more meaningful. To respond to the research question in what ways community inquiries create opportunities for students to explore social and cultural issues in their neighborhoods using multimodality?, we discovered that students' communities provided alternatives for creating meaningful learning environments in the EFL classroom, transforming mechanical and decontextualized language practices into flexible ways to communicate what matters to students. When students are intellectually and emotionally engaged, better learning is achieved (Wells, 1999). Language learning during this project became more than the reading of disclosed practices and accurate isolated words, it became the path to read our students worlds while scaffolding their learning process through the inclusion of multiple modes of representing meaning.

Exploring social and cultural issues through community inquiries provided students with foundations to think critically about their role in the community. It also broadened their possibilities for expressing different points of view regarding the problematic social situations that exist in their barrio. They also approached local cultural practices as a way to create resiliency towards those problems within their communities. Social networking with peers, parents, and the community of bloggers facilitated the expression of messages of resistance and resilience that emerged from the inquiry experience. Students used videos, audios, images, and texts as multiple modes of communication to express their learning about the community issues.

References

Barton, D., & Hamilton, M. (2000). Literacy practices. In D. Barton, M. Hamilton, & R. Ivanic (Eds.), Situated literacies: Reading and writing in context (pp. 7-15). New York: Routledge.

Blattner, G., & Fiori, M. (2011). Virtual social network communities: An investigation of language learners' development of sociopragmatic awareness and multiliteracy skills. CALICO Journal, 29(1), 24-43.

Burns, A. (2001). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clavijo, A. (2015a). Implementing community based pedagogies with teachers in Colombia to enhance the EFL curriculum. In M. Perales & M. Méndez (Eds.), Experiencias de docencia e investigación en lenguas extranjeras (pp. 31-43). Chetumal, México: Editorial Universidad Quintana Roo.

Clavijo, A. (2015b). Research tendencies in the teaching of English as a foreign language. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(1), 5-10.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Inquiry as stance: Practitioner research for the next generation. New York: Teachers College Press.

Dewey, J. (1990). The school and society: And, the child and the curriculum. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Dewey, J. (1997). Experience and education. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum.

García, O. (2009). Education, multilingualism and translanguaging in the 21st Century. In A. Mohanty, M. Panda, R. Phillipson, & T. Skutnabb-Kangas (Eds.), Social justice through multilingual education: Globalising the local (pp. 128-145). New Delhi: Orient Blackswan.

Haverback, H. (2009). Facebook: Uncharted territory in a reading education classroom. Reading Today, (27)2, 34.

Hubbard, R. S., & Miller, B. M. (1999) Living the questions: A guide for teacher-researchers. US: Stenhouse Publishers

Johnston, R., & Davis, J. (2008). Negotiating the dilemmas of community-based learning in teacher education. Teaching Education, 19(4), 351-360.

Kress, G. R. (2003). Literacy in the new media age. London, UK: Routledge.

Kozinets, R. V. (2010). Netnography: Doing ethnographic research online. U.S.: Sage Publications.

Kretzmann, J. P., & McKnight, J. L. (1993). Building Communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community's assets. Chicago, IL: ACTA Publications. Retrieved from http://www.abcdinstitute.org/publications/downloadable/

Majid, A. H.A., Stapa, H. S., & Keong, C. Y. (2012). Scaffolding through the blended approach: Improving the writing process and performance using Facebook. American Journal of Social Issues and Humanities. 2(5), 336-342.

Medina, R. A, Ramirez, L. M., & Clavijo, A. (2015). Reading the community critically in the digital age: A multiliteracies approach. In P. Chamness Miller., M. Mantero. & H. Hendo (Eds.), ISLS readings in language studies (Vol. 5; pp.45-66). Grandville, MI: International Society for Language Studies.

Mills, K. (2011). The multiliteracies classroom. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Moll, L. (1994). Literacy research in community and classrooms: A sociocultural approach. In R. B. Ruddell, M. P. Ruddell, & H. Singer (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (4th ed., pp. 179- 207). Newark: International Reading Association.

Murrell, P. C. (2001). The community teacher: A new framework for effective urban teaching. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Razak, N. A., Saeed, M., & Ahmad, Z. (2013). Adopting social networking sites (SNSs) as interactive communities among English foreign language (EFL) learners in writing: Opportunities and challenges. English Language Teaching, 6(11), 187-198.

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity and educational change. Harlow, England: Longman.

Quintero, L. (2008). Blogging: A way to foster EFL writing. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 10, 7-49.

Reyes, N. (2012). Engaging EFL learners in community based activities to develop their literacy processes in EFL. (Unpublished master's thesis). Universidad Distrital Francisco Joséde Caldas, Bogotá.

Rincón, J. (2014). Fostering students' inquiry skills through community based pedagogies. (Unpublished master's thesis). Universidad Distrital Francisco Joséde Caldas, Bogotá.

Scheter, S., Solomon, P., & Kittmer, L. (2003). Integrating teacher education in a community situated school agenda. In S. Scheter & J. Cummins (Eds.), Multilingual education in practice: Using diversity as a resource. Porstmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Sharkey, J., (2012). Community-based pedagogies and literacies in language teacher education: Promising beginnings, intriguing challenges. Íkala: Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 17(1), 9-13.

Shih, R. C. (2011). Can Web 2.0 assist college students in learning English writing? Integrating facebook and peer assessment with blended learning. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(5), 829-845.

Short, K. G. (2009). Inquiry as stance on curriculum. In S. Davidson & S. Carber (Eds.), Taking the PYP forward (pp. 11-26). Woodbridge, UK: John Catt Educational Ltd.

Somerville, M. (2010). A place pedagogy for 'global contemporaneity.' Educational Philosophy and Theory, 42, 326-344. doi:10.1111/j.1469- 5812.2008.00423.x

Warschauer, M. (2000). Online learning in second language classrooms: An ethnographic study. In M. Warschauer & R. Kern (Eds.), Network-based language teaching: Concepts and practice (pp. 41- 58). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Warschauer, M., & Kern, R. (Eds). (2000). An electronic literacy approach to network-based language teaching network-based language teaching: Theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic inquiry: Towards a sociocultural practice and theory of education. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wells, G. (2008). Dialogue, inquiry and the construction of learning communities. In B. Lingard, J. Nixon, & S. Ranson (Eds.), Transforming learning in schools and communities (pp. 236-256). London: Continuum.

Wells, G., & Claxton, G. (2002). Learning for life in the 21st century: Sociocultural perspectives on the future of education. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Whitin, P., & Whitin, D. J. (1997). Inquiry at the window: Pursuing the wonders of learners. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Métricas

Licencia

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/