DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a04Publicado:

2015-10-23Número:

Vol 17, No 2 (2015) July-DecemberSección:

Artículos de InvestigaciónTransactional reading in EFL learning: a path to promoting critical thinking through urban legends

La lectura transaccional en el aprendizaje del inglés: una ruta para promover el pensamiento crítico mediante las leyendas urbanas

Palabras clave:

habilidades de pensamiento crítico, aprendizaje del inglés, estudiantes críticos, leyendas urbanas, enfoque de lectura transaccional (es).Palabras clave:

critical thinking skills, critical learners, EFL learning, urban legends, transactional approach. (en).Descargas

Referencias

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives. Complete Edition, New York: Longman.

Bell, J. (2005). Doing your research project (4th ed.). New York: Open University Press.

Bloom, B. S.; Engelhart, M. D.; Furst, E. J.; Hill, W. H.; Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

Brunvand, J. H. (1981). ‘The Vanishing Hitchhiker’ American urban legends & their meaning. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

______. (1999). ‘Too Good to be True’ The colossal book of urban legends. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Carrell, P. L., & Carson, J. G (1997). Extensive and intensive reading in an EAP setting. English for Specific Purpose, 16(1), 47-60.

Corbin, J. & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cortázar, F. (2008, Enero-Junio). Esperando a los bárbaros: leyendas urbanas, rumores e Imaginarios sobre la violencia en las ciudades (Waiting for the Barbarians: urban legends, rumors and collective imagination about violence in cities). Nueva época, 9, 59-93.Universidad de Guadalajara.

Dewey, J. and Bentley A. (1949). knowing and the known. Boston: Bacon Press.

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Millbrae, CA: The California Academic Press.

_______. (2007). Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. Millbrae, CA: California Academic Press. Retrieved on April 5th from:

www.insightassessment.com/pdf_files/what&why2007.pdf–

Fecho, B. & Amatucci, K. (2008). Spinning out of control: Dialogical transactions in an English classroom. English Teaching: Practice and Critique. 7 (1), 5-21.

Heda, J. (1990). 'Contemporary legend'. To be or not to be? Folklore, 101 (2), 221- 223, Taylor & Francis, Ltd. On behalf of Folklore Enterprises, Ltd.

Johnson, B. & Christensen, L. (2004). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. USA- Pearson Education. Inc.

Koshy, Valsa. (2005). What is Action Research? Action Research for Improving Practice, London: Paul Chapman Publishing

Merriam, S. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Franciaco: Jossey-Bass.

Nosich, G. (2009). Learning to think things through: A guide to critical thinking in the curriculum. Columbus, OH: Pearson.

Parsons, R. D. & Brown, K. (2002).Teacher as reflective practitioner and action research. Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2007). Critical thinking competency standards. Foundation for Critical Thinking Press.

Pineda, C. (2003). Searching for improved EFL classroom environments: The role of Critical thinking-related tasks. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia. Colciencias.

Probst, R. E. (1987). Transactional theory in the teaching of literature. ERIC Clearinghouse.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1995). Literature as exploration (5th ed.). The Modern Language Associations of America.

______. (2002). La literatura como exploración. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

______., & Karolides, N. (2005).Theory and practice: An interview with Louise M. Making meaning with texts. (Selected essays).

Sitima, J., Maulidi, F., Mkandawire, M., Chisoni, E., Samu, S., Gulule, M., & Salanje, G. (2009). Reading skills. Communication skills. Malawi: Bunda College of Agriculture University.

Sternberg, R. J. (1986). Critical thinking: Its nature, measurement, and improvement National Institute of Education. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED272882.pdf.

The Center of Teaching and Learning. ( 2005, Fall). Using class discussions to meet your teaching goals. In: Newsletter on Teaching. Stanford University: NEWSLETTER. 15, (1), 1-6.

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a04

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Transactional reading in EFL learning: A path to promoting critical thinking through urban legends

La lectura transaccional en el aprendizaje del inglés: una ruta para promover el pensamiento crítico mediante las leyendas urbanas

Luis Fernando Gómez Rodríguez1 Mariela Leal Hernández2

1 Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, Bogotá, Colombia. lfgomez@pedagogica.edu.co

2Colegio El Cortijo-Vianey IED, Bogotá, Colombia. maryela108@yahoo.es

Citation / Para citar este artículo: Gómez, L. F. & Leal, M. (2015). Transactional Reading in EFL learning: A path to promoting critical thinking through urban leyends. Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J. 17(2), pp. 229-245.

Received: 09-Jun-2014 / Accepted: 25-Aug-2015

Abstract

This article reports an action-research study3 that attempted to develop EFL4 eleventh graders’ critical thinking through the transactional reading approach. Since learners were used to taking grammar-oriented English classes and had negative attitudes towards reading, they were encouraged to do reading transactions with the support of urban legends. These legends inspired them to discuss social conflicts (loss of values, drug consumption, alcoholism, risky lifestyles, etc.) that related to the problems of the insecure and vulnerable neighborhood in which they lived in Bogotá. Data were collected from teachers’ observations, interviews with students, and worksheets (artifacts) in a pedagogical intervention. Through the grounded approach analysis, it was found that learners fostered critical thinking as they criticized human behaviors, generated solutions to correct questionable behaviors, and produced knowledge based on previous information in the foreign language.

Keywords: critical thinking skills, critical learners, EFL learning, urban legends, transactional reading.

Resumen

Se reporta un estudio de investigación acción cuyo objetivo fue desarrollar el pensamiento crítico de un grupo de estudiantes de inglés a través del enfoque de lectura transaccional. Debido a que los estudiantes estaban acostumbrados a clases de inglés con un énfasis gramatical y tenían actitudes negativas hacia la lectura, fueron incentivados a hacer transacciones de lectura con el apoyo de varias leyendas urbanas. Estas leyendas los inspiraron a discutir conflictos sociales (la pérdida de valores, el consumo de drogas, el alcoholismo, estilos de vida riesgosos, etc.) que de alguna manera se relacionaban con los problemas de la localidad insegura y vulnerable donde vivían en Bogotá. Se recogieron datos por medio de las observaciones de los profesores, las entrevistas a estudiantes y de talleres hechos en la intervención. Mediante el método de análisis fundamentado en los datos, se halló que los estudiantes construyeron pensamiento crítico al lograr criticar comportamientos humanos, generar la solución de conflictos personales y sociales y planear y producir nuevo conocimiento a partir de información previa. Otro hallazgo importante es que fueron críticos expresando sus opiniones en la lengua extranjera.

Palabras clave: habilidades de pensamiento crítico, aprendizaje del inglés, estudiantes críticos, leyendas urbanas, enfoque de lectura transaccional

Introduction

Developing critical thinking has become an important issue in EFL education. It not only helps learners to read and comprehend reading materials assigned at school, but also to understand, analyze, and evaluate different unfair situations at their school or in their community. Accordingly, it is crucial for EFL students to enhance different cognitive skills by going from the literal meaning to a critical standpoint when being exposed to reading and oral discourse. That is why this investigation attempted to stimulate eleventh graders’ critical thinking skills in an EFL classroom at a public high school in Bogotá, Colombia, during the reading of urban legends, a genre that has almost been overlooked in the foreign language classroom.

According to a needs analysis carried out in February, 2013, supported by the use of systematic observations and a diagnostic interview, we, teacher researchers, identified several limitations in an eleventh grade class. English classes were mainly focused on grammar learning accompanied by drilling, repetition, and memorization of structures and vocabulary, with few opportunities for learners to practice the language more communicatively. In addition, students came from low socio-economic levels, a situation that forced the school to forbid the use of textbooks because students simply could not afford them. As a result, most of the classes were based on the teacher’s explanations on the board and on modest in-house materials. Because the school had limited teaching resources, one of the goals of this investigation was to provide students with urban legends which are authentic but inexpensive materials for them to practice reading, writing, and speaking skills in class.

Another limitation was learners’ lack of critical thinking skills in reading practices. Reading was restricted to learning vocabulary and checking basic reading comprehension activities. It was detected that most learners neither understand the texts fully nor gave any opinion about the materials because it was difficult for them to go beyond the literal meaning. In this way, they demonstrated negative attitudes towards reading in English because they simply disliked it. Besides, these students made the effort to come to class every day in spite of the fact that they had family problems, lacked money and basic supplies to live, and were affected by social violence, insecurity, and intolerance in the neighborhood. Within this context, none of the school subjects were important for their own lives and many of them wanted to leave school to get a job.

Because of these difficulties, we sought to change the traditional teaching practices into a more meaningful and motivating experience by inviting learners to read urban legends, an appealing kind of authentic material that could encourage them to become better critical readers. These legends contained topics about the loss of values, risky lifestyles, and problems in contemporary societies, clearly visible in this group of learners’ own social context and personal lives.

Theoretical Framework

Critical Reading from a Transactional Approach

One of the main proponents of the transaction reading approach has been the influential American author Rosenblatt who used the concept “transaction,” a word coined from Dewey and Bentley (1949), to refer to the close relationship between the reader and the text. The reader is modified, activated, and moved by the text and the text acquires its meanings when the reader brings his/her personal background, feelings, knowledge, and experiences to the reading. In this line of thought, Fecho and Amatucci (2008) state that readers interpret and shape original texts before them while those texts equally shape readers. Thus, the text and the readers modify one another.

Rosenblatt (2002) claims that each reader is able to find different interpretations of a text. Interpretations could differ from the author’s actual intention and among readers’ interpretations when reading the text in different contexts and from a variety of personal situations. However, interpretations are only valid when they are founded on substantial evidence in the text. Rosenblatt (1995) argues that there is not a single correct interpretation of any text for all circumstances. Diverse interpretations are valid when they depend on a responsible reading process, accompanied by a reasonable and solid basis found in the text. Hence, readers must be receptive to accept different interpretations of a text if those interpretations are well supported. In the classroom, the role of a teacher is not to expect from students one final and unique conclusion, but to be ready to recognize multiple possibilities of meaning constructions and opinions based on evidence (Probst, 1988). In this way, this research study claims that EFL education should adopt the transactional approach in order to provide learners with opportunities to make reading transactions with the texts while playing with numerous levels of interpretation built on logical support. In fact, Rosenblatt (1995) says that teaching should enhance the individual’s capacity to make meaning from the text by leading him/her to reflect self-critically, a statement which resonates with critical thinking development.

Moreover, Rosenblatt (2002) asserts that the transactions with texts involve the reader’s inevitable conscious or unconscious effort to deal with ethical attitudes and issues. It is almost impossible to read and discuss a novel, a play, or any other literary work without facing any ethical and moral dilemmas. This particular notion was significant for this study because urban legends are chiefly reading materials that have to do with moral and ethical dimensions of human life, a characteristic that associates with Rosenblatt’s (2002) notion that critical reading ultimately aims at the improvement of human life.

Urban legends

Another central construct that is articulated with the transactional approach is the incorporation of American urban legends in the EFL classroom, a reading material that possesses salient characteristics suitable for EFL learners’ needs. Urban legends are a widespread form of modern folklore created to entertain readers of all ages who mainly live in big cosmopolitan cities. They contain stories reflecting social dangers, mysteries, and conflicts people face in contemporary society, namely fraud, theft, juvenile crime, kidnapping, and drug consumption (Brundvand, 1981; Cortázar, 2008; Heda, 1990). Characters are victims of strangers’ and close friends’ evil nature, and danger can be at schools, in the neighborhood, and in the social networks like Facebook and Twitter. These stories depict individuals’ personal dilemmas, beliefs, superstitions, and odd experiences, topics that result in being interesting materials for learners in modern societies. As a form of pop culture expression, these contemporary folk tales have been transmitted from one friend to another orally, through photocopies known as “Xerox-lore” before the age of the Internet, and ICT media such as e-mail and web pages in modern times. Brunvand (1999) indicates that urban legends describe presumably real (though odd) events that happened to a friend of a friend. Therefore, the narrator must have the capacity to tell the stories in a believable style to convince the recipient that those events were true. They typically start with the sentence “This is a story that happened to a friend,” which means that the strange situations might also happen to us. Cortázar (2008) points out those urban legends contain a social function because they not only convey the social problems of contemporary life, but create awareness of the decadence of modern civilization. Also, urban legends possess a moralizing message because their characters have to struggle with daily immoral dilemmas that involve dishonesty, irresponsibility, disobedience, and taking advantage of innocent people, putting to the test individuals’ moral and ethical system of values. This feature closely relates to Rosenblatt’s (2002) claim that reading necessarily implies an attempt to deal with man’s ethical nature. In particular, the authors of this research project highlight that urban legends are authentic materials that encourage English learners to read real language in use, portraying adolescents’ and young adults’ lifestyles and experiences. According to Brunvand (1981), the language in these materials seems to convey true and relevant information presented in an attractive way, with possibilities to work on meaning construction. Moreover, they have the characteristic of being modified and adapted as each person adds or deletes events in the stories in order to make them closer to readers’ or hearers’ own reality and local conditions. In this sense, EFL learners can read urban legends as well as participate in their narration in written and oral form, and share them among friends with new adaptations hinged on their personal life experiences.

Critical thinking

Critical thinking can be understood as the mental process involving a “purposeful, self- regulatory judgment” (Facione, 1990, p. 3) that enables the capacity for interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference of information. Such information is collected from observation, experience, reflection, and reasoning (Facione, 2007; Nosich, 2009). Most importantly, critical thinking embodies the mental strategies to solve problems of real life, make decisions, answer questions, and learn new information (Sternberg, 1986). Being critical is a way to respond reasonably to the information received with which mental processes such as judgment, analysis, and evaluation occur.

With critical thinking, understood from a critical literacy perspective, learners become more mentally dynamic and decisive rather than passive receivers of contents in the classroom. That is why critical thinking must be fostered at schools in all areas of knowledge including EFL learning because learning a foreign language is more significant when critical thinking skills are used to promote communication and meaning negotiation (Pineda, 2003). According to Wallace (1999), second language development can happen through analytic reading of texts and critical discussions around texts, and critical interpretation of texts needs to be dependent on the appropriate understanding of the language system. Wallace also states that “readers are in a position to bring legitimate interpretations to written texts. They are able to exploit their positions as outsiders”(1992, p.68). Moreover, Perales Escudero (2012) claims that pedagogies on second language learning should enable students to infer meaning by examining texts analytically. Nevertheless, those critical reading skills need to be enhanced progressively by doing reason-based tasks and choices (Paul & Elder, 2005) that can eventually help learners to face and analyze situations of everyday life.

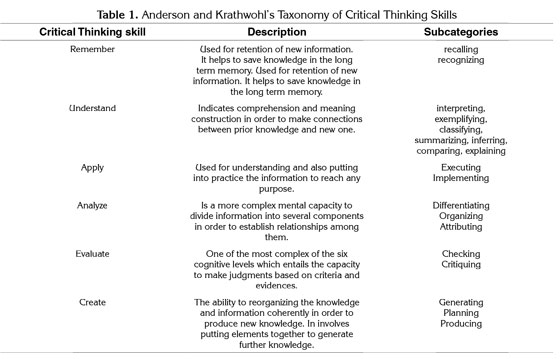

The set of critical thinking skills implemented in this research study was Anderson and Krathwohl’s (2001) taxonomy which was also refined by Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill, and Krathwohl’s (1956) classification. Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) identify six actions or bare verbs to represent the critical thinking skills as mental processes in action rather than rigid states. This change in the nomination of the categories from nouns to verbs denotes movement. They are organized in a hierarchical order, going from the most basic to the most complex, suggesting that they can be developed progressively through mental practice (see Table 1). It is essential to keep in mind that these six skills are subdivided into several subcategories.

With the help of these thinking skills, this project attempted to develop critical reasoning and problem solving skills when EFL learners were involved in the discussions of urban legends. EFL teachers should create environments in which learners may feel comfortable with reading transactions and class discussions because debating and interacting with others can generate critical ideas and new meanings socially constructed in the foreign language. As stated by Paul and Elder (2005), to understand content in books, films, or media messages, a person must understand not simply the raw information, but also its purpose, meaning, the assumptions underlying it, and the conclusions from a critical standpoint.

Methodology

This research was conducted at a public high school in Usme, Bogotá, an area mostly inhabited by working-class people. Many of the inhabitants face social problems of alcoholism, drug consumption, violence, and delinquency. These people experience socio-economic limitations due to lack of money, scarce job opportunities, and social inequality. The school supports students in the development of their own personalities, social relations, and cultural identities in order to help them become better citizens. The school curriculum is supported by Hermes, an educational community program sponsored by Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá. It seeks to promote a culture of peace and non-violence in schools with the use of conflict resolution strategies. This investigation relates in part to the institution’s plan to build critical thinking and exemplary citizenship skills by encouraging the participants to critically address common problems in their lives through the transactional reading of urban legends. Thus, this study aimed at answering the following research question: Could a group of eleventh-grade EFL learners build critical thinking skills through the transactional reading of American urban legends at a public school in Bogotá, Colombia?

Research Type

This was an action research project that, after identifying a problem in the classroom (see statement of the problem), developed a plan to solve it. Action research is an inquiry approach suitable for educational contexts where knowledge and solutions are required for a specific problem (Bell, 2005). Action research involves systematic observations and data collection during a pedagogical intervention in which a plan is developed to solve the problem. Later, the data are used to reflect, make decisions, and generate the development of more effective classroom strategies (Parsons & Brown, 2002). Thus, the main objective of this study was to observe whether learners were able to become critical readers when they reflected on certain social problems involving their friends, the community, and the city during the discussion of urban legends in the foreign language. The goal was also to help learners use the target language more communicatively while they were involved in reading transactions in the EFL classroom.

Participants

This study was conducted with 32 EFL learners in eleventh grade (14 males and 18 females) who were 15 to 18 years old. The majority did not like to study, and they would have liked to leave school in order to get a job. The lack of money and the effects of violence at home, school, and their community reduced their motivation to study. They possessed a low English level due to the fact that they never studied English in primary school, and in secondary school they only had English classes two hours a week. As a result, the students had problems with vocabulary and grammar rules, and they did poorly when reading and speaking in English. Nonetheless, they were curious and cooperative when they were involved in class projects that broke up class monotony, as happened with this study.

Data collection instruments

We took field notes every class session which focused on EFL learners’ critical comments on the events and characters of the stories as well as their commentaries on their own lives and experiences. These notes were supplemented by video recordings, so notes were taken after the end of each session through the reported speech technique (paraphrasing what students said without using the exact words, a technique we decided to use) or by entering verbatim utterances of learners’ voices. Field notes were chosen because they were not only useful for keeping record of significant events but also helped the researchers reflect on what was observed with analytical opinions about the notes taken (Koshy, 2005). Extended notes were also taken right after class as the researchers reflected on the experience. These notes were saved in computer files to later analyze the data.

Semi-structured interviews were also used. Interviews established dialogues with the participants by asking questions to elicit information that was not otherwise possible to be observed, including thoughts, beliefs, knowledge, reasoning, motivations, and feelings about the experience (Johnson & Christensen, 2004). In this study, interviews focused on identifying students’ perceptions concerning their own thinking process when reading and discussing American urban legends. Most of the questions were open questions that allowed the researchers to formulate follow-up questions according to the interviewees’ responses. The interviews were in Spanish to help students express freely their perceptions about the experience, and were done at the end of the pedagogical intervention (see Appendix A).

The third data collection instrument consisted of the worksheets that the participants completed during the pedagogical intervention. These worksheets served as artifacts. Artifacts are the materials used or manipulated by the participants during the research process (Merriam, 1998). In this sense, artifacts enabled the researchers of this study to be reflective because they contained participants’ direct written answers, thoughts, and ideas about the readings and the topics addressed in class which were written in the English language. Each worksheet presented an urban legend, complemented with pre-reading questions, key vocabulary, and some open questions that guided the critical discussion (see Appendix B). Artifacts were collected at the end of the classes, photocopied, and saved in a folder to assure confidentiality of the data.

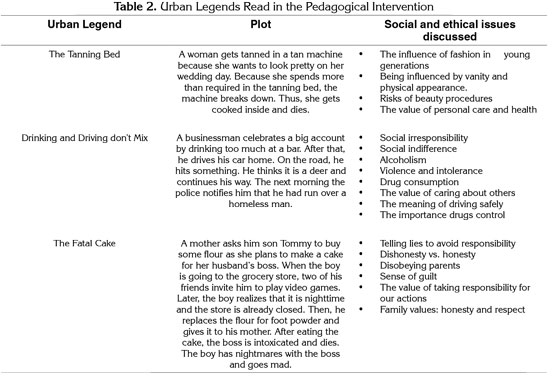

Pedagogical intervention

The pedagogical intervention took place from March 6 to May 31, 2013. It was developed in light of the principles of the transactional approach. For the purposes of this article, three urban legends were selected5(see Table 2).

First stage: Individual intensive reading

Individual intensive reading is ideal for short texts because it is concerned with inferring and analyzing specific information or details, so it demands more careful and deeper reading. Intensive reading requires the discovery of different interpretations, the author’s intentions, and reconstructions of a text framed in transactional processes between the reader and the reading material (Carrell & Carson, 1997). Accordingly, during the pedagogical intervention, students read the selected urban legends individually with the support of worksheets (see Appendix B) in which they were asked to answer several questions about what they read. Individual reading was developed in the classroom while the teachers walked around to monitor and help students complete the tasks. Students asked questions about vocabulary, asked for clarification, and called the teachers to review and correct their answers. Worksheets included pre-reading activities that activated their prior knowledge, allowed them to make predictions about the readings, or led them review and learn vocabulary that they found later in the urban legends. After reading the material, the students completed several post-reading tasks that encouraged them to critically address in written form their personal opinions about the events that happened in the urban legends. The individual reading and worksheets intended to follow Rosenblatt’s (1995) advice that the teachers’ task is to foster productive interaction or transactions between individual readers and individual literary works. Thus, with the worksheets, learners were able to establish individual transactions with the texts to construct meaning in a purposeful way.

The individual reading process was slow and somewhat difficult at the beginning of the intervention because of the students’ low level of English. However, they usually used the dictionary and asked the teachers questions to complete the tasks in the worksheets. Despite the challenge, the students made individual efforts and gradually got used to individual readings as they realized that they were enjoying the urban legends. Indeed, this individual work made them feel safer when they later participated in class discussions because they had enough time to prepare the tasks and think about the stories beforehand.

Second stage: Group intensive reading

As proposed by the transactional approach, “the literary work, like language itself, is a social product” (Rosenblatt, 1995, p. 28). Consequently, after the individual stage, students had the opportunity to establish transactions with their classmates in small groups. They compared, shared with, and helped each other with the answers in the worksheets. Students felt comfortable in this step because it facilitated social transactions to clarify aspects that they could not understand individually and promoted initial discussions of the topics presented in the urban legends.

After this step, the whole class held discussions in which students were able to participate and express their points of view about the characters’ actions and behaviors in the urban legends critically. Discussions were supported by the previous work they had done on the worksheets. Learners were shy and hesitant at the beginning, so the teachers always worked as mediators by asking questions to trigger discussion. The students increasingly engaged in debates, these being interesting social transactions in which richer meanings were raised. These social transactions enabled learners to evoke multiple meanings from the texts and to reflect critically on this process (Rosenblatt, 1995).

Data analysis

The grounded-theory approach was used for data analysis (Bell, 2005; Merriam, 1998; Patton, 2002). The analysis followed the three steps suggested by Corbin and Strauss (2008). In the microanalysis step, meaningful and repeated sentences were identified in the field notes and the artifacts through a process of triangulation. They were relevant information related to the critical thinking skills students had used and the reading transactions they had established. In the opencoding

step, patterns were grouped with a technique

named color coding until important pre-categories

emerged. For example, the data showed that the

participants frequently criticized wrong behaviors of

the characters in the stories and in their own lives

which are clear examples of critical thinking skills.

Hence, pre-categories related to the skill criticize

were colored in green. Criticize also represented the kind of reading transaction the students had

come up with from the urban legends as it was solid

evidence that the they had evoked meaning from

the texts, leading them to reflect on the events and

characters.

In the axial-coding step, the data were organized

into final categories which embodied the patterns

and the pre-categories previously identified. Three

main findings, encapsulated into categories,

were identified in the data analysis. It was found

that the students obviously used the basic critical

thinking skills, remember, understand, and apply

during the pedagogical intervention. However,

this analysis centers on the development of more

complex skills because this was the participants’

major achievement.

Results

Students criticize fictional characters’ irresponsible behaviors and their own p

One of the main findings in the field notes and the artifacts is that both individual and social transactions allowed learners to criticize what they thought were incorrect behaviors of the fictional characters in the urban legends and relate them to similar wrong behaviors of people they knew in their own lives. Critiquing is one of the critical thinking subcategories that belongs to the category evaluate (see Table 1) which is understood as the capacity to make judgments supported by genuine facts and evidence. One example is when the students discussed the legend “Drinking and Driving Don’t Mix” (see Table 2). A student said that the businessman in the story was irresponsible because “he was in the state of drunkenness driving a car and kill one person. 6 ” Another student said that the businessman was coding step, patterns were grouped with a technique named color coding until important pre-categories emerged. For example, the data showed that the participants frequently criticized wrong behaviors of the characters in the stories and in their own lives which are clear examples of critical thinking skills. Hence, pre-categories related to the skill criticize were colored in green. Criticize also represented irresponsible because “he was driving with alcohol in his body,” and when “he crashed the homeless man he no stop to help him” (field notes, May 22, 2013).

In the previous examples, the students criticized the businessman’s irresponsible driving because he had killed another human being. In this event, urban legends became exemplary stories, containing moral messages for the students. They facilitated critical reflections about how the characters resembled real people the students knew who likewise performed “irresponsible actions.” Thus, students addressed the negative consequences of drinking alcohol in excess. They believed that alcoholism was one of the most serious problems of some of their relatives, neighbors, and well-known people in the city because drinking “change people’s conduct in a negative way,” as was also presented in the story. They said that “drunks lose their mental and physical normal functioning,” affecting others’ lives and families with “violence and intolerance” (field notes, May 22, 2013). Thus, it seems that transactional readings of the urban legends helped the learners critique issues related to alcoholism and social irresponsibility.

Similarly, data showed that when the participants read the urban legend “The Fatal Cake” (see Table 2), they strongly criticized Tommy’s dishonesty.

Erika: “Tommy no obey to his mother and tells lies, because he preferred to play with the friend” (student artifacts, May 29, 2013).

Alex: “He disobeyed his mother when she asked him to buy flour. He also lied to her because he replaced the flour for foot power” (student artifacts, May 29, 2013)

The reading transactions led students to judge Tommy’s behavior in disobeying and deceiving his mother in order to evade any punishment as wrong. The learners were thoughtful about the consequences of telling lies. Indeed, they discussed how, at the end of the story, Tommy probably regretted having caused the death of the man who had eaten the cake (made from foot powder instead of flour). They mentioned that Tommy probably “had feelings of guilt and remorse” and even “had nightmares because of his bad actions” (field notes, May 29, 2013). Thus, with the reading transactions, students critically analyzed how telling lies and disobeying parents can cause negative consequences.

This discussion encouraged students to remember times when they had lied to their parents, such as when they had gone to a party without asking for permission or had hung around with friends their parents did not like. They remembered that their parents had found out about their misbehavior and had punished them for being insincere (field notes, May 29, 2013). Thus, as suggested in Rosenblatt’s (2002) approach to reading transactions, these EFL learners had the opportunity to be critical thinkers, enthused by the contents in the urban legends. They found significant meanings when they read them and established personal connections to their own experiences as they spoke about distrust, dishonesty, and disobedience as well as the importance of being frank with their parents.

Likewise, when reading the urban legend “The Tanning Bed Myth,” the students criticized the woman’s obsession with tanning because she was engaging in dangerous beauty treatments in order to meet the physical beauty standards that the media, advertisement, and society imposed:

Carmen: “The society and fashion establish beauty rules and we don’t decide about our own likes, people tend to follow fashion without thinking well about risks” (student artifacts, April 29, 2013).

Consequently, participants evaluated the questionable behaviors of the characters in the urban legends and related these to their own lives as they critiqued the negative influence of fashion and mass media on younger generations.

Based on these analyses, it can be seen that one of the most complex critical thinking skills students used to support their opinions was critiquing human actions. Importantly, EFL learners were able to express these opinions in the foreign language through meaningful personal and social transactions instead of just studying grammar forms.

Students generated solutions to correct questionable behaviors

When the students discussed the topics presented in urban legends, they were able to generate solutions to correct questionable behaviors. As mentioned in the theoretical framework, generating is one of the complex cognitive thinking skills established by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001). It belongs to the category create, and it consists of providing alternatives to overcome difficult circumstances by constructing different hypotheses. The generation of solutions to correct people’s questionable behaviors took place while the students discussed the moral implications of telling lies when they read “The Fatal Cake.” Even though it was a fictional story, the participants realized that both serious and white lies might cause distrust, misunderstanding, and even deadly consequences. Therefore, they generated solutions to stop lying and deception. For example, in the artifacts, they changed the events of the story by showing the way Tommy should have corrected the mistake of having forgotten the errand for his mother:

Diego: Tommy saw that the store was [already] closed and ask friends for the help with flour, and the friend gave it to tommy. He went home and gave the flour to his mother. She made the cake and all liked it.” (student artifacts, May 29, 2013)

Despite several language limitations, this student generated a solution in regards to Tommy’s questionable behavior, which basically can be summarized as: Tommy should have borrowed some flour from a friend instead of deceiving his mother by making the cake with a harmful ingredient. Other students expressed in their versions of the urban legends that being honest and obedient is always the best behavior to avoid having serious troubles with the people we care about. The interview also captured students’ critical reflections on this matter:

Teacher: ¿Qué aprendiste en cuanto a los temas de los textos?

Sandra: Sí, digamos por ejemplo a ser más responsable, a no decir mentiras (.) con el fin de evitar accidentes y malentendidos. Es mejor ser honesto. (interview, June 6, 2013)

As can be seen, the transactional process with the reading material helped this participant to generate a crucial solution for his life: to try to avoid telling lies from now on, since the story had taught him the ethical value of honesty.

When discussing “The Tanning Bed Myth,” students generated solutions to take care of one’s physical appearance in a responsible way. They highlighted that although looking good and dressing well are important for self-esteem, people must be careful about risking their lives with beauty products, as illustrated in these examples:

Juan: “Vanity is good, but also the care that the person has of her body and not risk her health.” (student artifacts, April 29, 2013)

Andrea: “Physical appearance is important, but we have be careful with bad beauty products.” (student artifacts, April 29, 2013)

Through the transactions established in class, the participants affirmed their belief in the importance of caring for one’s physical appearance. Nevertheless, they also provided a solution to extreme vanity: avoiding the overuse of certain beauty products or treatments such as tanning, self-medication, overly strict diets, and plastic surgery without the correct safety rules and medical support (field notes, April 29, 2013). Similar views were found in the interviews:

Teacher: ¿Qué aprendiste en cuanto a los temas de los textos?

Andrés: Aceptarse uno tal y como es. Hay veces que uno piensa que llevando la vanidad hasta el extremo pues no va a pasar nada, pero: sí puede traer sus consecuencias. (interview, June 6, 2013)

It can be assumed that the students were able to generate solutions to correct irresponsible and immoral conduct that they thought were similar to those with which they were already familiar from their own experience. This finding is closely related to one of Rosenblatt’s transactional reading principles: that the reading process should cause the reader’s conscious or unconscious discernment to analyze ethical principles to ultimately preserve and respect his/her own and others’ lives. In fact, the participants learned about and reflected on useful moral lessons to improve their lives:

Teacher: ¿En tu opinión, se deberían o no incluir las leyendas urbanas en la clase de inglés?

Martha: Sí, pues para que sea más interactiva la clase y pues para que se aprenda más aparte de inglés sobre la honestidad, el respeto y esas cosas. (interview, June 7, 2013)

In this example, the student recognized the importance of the urban legends, not only as a means for studying the foreign language, but also for learning about human values that are necessary for their personal growth. Since urban legends have a moralizing intention, learners spontaneously generated solutions when they were encouraged to express their opinions about the moral dilemmas presented in the legends. They referred to human virtues such as self-respect, honesty, trust, obedience, and the prevention of any unsafe beauty treatment. Similarly, students rejected human actions they thought were incorrect such as driving under the effects of alcohol, telling lies to deny responsibility, and being negligent with health care.

Students created new knowledge based on previous information

One of the main findings in the data is that students were able to develop complex thinking skills such as planning, generating, and producing knowledge during the reading transactions with the urban legends, all of which belong to the skill create (see Table 1). Creating is the ability to rearrange or reorder knowledge and information to complement existing or produce new knowledge (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). It involves putting elements together to generate further knowledge. The students used this skill when they were encouraged to work in groups to write and modify the urban legends as they liked, this being an authentic task because urban legends are a collective literary creation that change relatively from one person to another. A clear example of creating was when learners read “Drinking and Driving Don’t Mix” (See Table 2), a legend dealing with the dangers of alcohol consumption. Learners created a similar story:

“Once upon a time one boy named pepito was very depressed because in his house there was much problems and nobody pay attention to him. He let himself guide by bad friends, he begin to consume drugs. Pepito was under bad influences, one day he was in a fight in the street, he was killed by a stab.” (student artifacts, May 22, 2013)

Even though this urban legend was written with some grammatical mistakes, it is an example of how participants created meaning by modifying and recreating the original urban legends as they were motivated by the story they had read to remember a similar experience from their own lives. With regards to the topic of alcoholism addressed in “Drinking and Driving Don’t Mix,” the example indicates that the participants made several changes. They recreated and rearranged the story by telling the experience of a teen boy who was under the effect of drugs, instead of alcohol. The students’ version implies that drugs may bring serious consequences such as violence and death. Similarly, this version addresses the risk of trusting bad advice from friends that may lead to poor decisions, like fighting with others. This version contains several features of urban legends, counting on a social conflict and a moral situation. In order to create this new story, the students necessarily planned the logical order of the events related to the effects of consuming illegal substances. They also generated a moral message and produced critical knowledge as the story reveals students’ disagreements about drug taking amongst adolescents, a serious problem that they faced daily in their neighborhood. In this sense, the students reflected critically about a social problem of their community as they made transactions between the original urban legend they read and the stories they created later.

Planning, generating, and producing were also critical thinking skills that learners developed when they performed the urban legends on stage, as happened for instance when they planned and role- played a different version of the urban legend “The Fatal Cake”:

The next group’s role-play was about Tommy. Students did the following modifications: Tommy did not buy the flour as the store was closed. So he went home and told the truth to his mom. He said to her that he had not bought the flour for the cake because he had disobeyed her. Instead of going to the supermarket and buy the flour, he went to play soccer with his friends. Tommy recognized his mistake and his mother forgave him. Later he went to a neighbor’s house and borrowed some flour for the cake. (field notes, May 31, 2013)

By modifying the original urban legend, the learners showed their creative capacity and ability to apply their understanding that honesty and responsibility are important human values that aid in establishing good relationships with other people. As can be seen, they created a fictional character, Tommy, who told his mother the truth, a situation that is closely related to their own lives as they similarly have occasion to decide whether or not to lie to their parents and teachers. In groups, students planned their written texts and wrote new versions of urban legends by adding events derived from their own experiences. This relates to Brunvand’s (1981) notion that with urban legends “many changes are predictable adaptations to make the stories fit the local conditions (…) circumstantial details of name, place, time and situation often enter into narrator’s performance” (p. 3).

With the help of the transactional reading approach, the participants showed their ability to create stories in the foreign language by creatively combining their own knowledge, experience, and imagination, with the information in the readings. Students perhaps expressed their most critical point most clearly in the role-play: that it is better to be honest with people than rather telling lies because students believed fraud always brings punishment.

The interviews also confirm that students valued the opportunity to enhance the creating skill:

Teacher: Cuéntame de tu experiencia trabajando con leyendas urbanas en clase de inglés

Freddy: No, pues uno aprende también a comprender textos, a crear sus propias historias en inglés. (Interview. June 7th, 2013)

Angélica: Porque uno le enseña a los demás cómo los actos que uno hace pueden traer buenas y malas consecuencias. (Interview. June 6th, 2013)

Teacher: ¿De qué forma se discutieron las leyendas urbanas?

Tomás: Uno eh opina, escucha la opinión de los demás y complementa y relaciona con la vida de uno y como digamos que sí, uno ya ha vivido esa experiencia y vuelve a reflexionar. (Interview, June 6th, 2013)

In these samples of data, Freddy recognized the opportunity he had to not only understand (a basic critical thinking skill), but create (a complex skill) imitations of urban legends in the target language. This is one of the study’s main achievements that EFL learners used the foreign language as a vehicle to produce meaning through their own inventive capacities. Moreover, the transactional reading approach encouraged learners, as Angélica and Tomás observed, to listen to others’ opinions and, most importantly, to relate the events of the urban legends to their own lives. Through a creative literary process, they planned and generated reflections on their own past questionable choices. As Rosenblatt (2002) observes, the transactional approach embraces the principle that what the student or reader gives to the text is as important as the text itself. Thus, the learners did not just read the urban legends in isolation and only for the sake of completing a reading comprehension task; they were actually able to establish close relationships between the events in the urban legends and their experiences and knowledge of the world as they recreated, enriched, and complemented the urban legends from a critical and creative learning standpoint. Indeed, any literary materials (in this case, urban legends) have the potential to contribute to students’ visions of the world, themselves, and the human condition (Rosenblatt, 2002). The learners in this study were able to express their visions of the world through the creating skill.

Conclusions

The transactional approach to reading was found to be a useful method in the EFL classroom in that it encouraged learners to build critical thinking skills as they established individual transactions with the texts and social transactions with their partners. They were able to express their opinions on the issues presented in the urban legends to others. Those critical opinions were also related to learners’ personal lives and knowledge of the world, meeting the goals of the transactional approach which claims that the reader brings to the reading process his/her own reality. Rosenblatt (2002) argues that when the ideas presented in the readings have no relevance to learners’ past experiences or emotional necessities, the reading process results in a negative, weak, and vague experience. In contrast to this, the reading experience in the pedagogical intervention was closely related to the interests and problems that these young adolescents had in their own lives.

Students were able to develop high level critical thinking skills such as criticizingquestionable choices generating solutions to conflicts, and creating new knowledge based on previous information through the reading of urban legends. These were the greatest accomplishment of the participants since they had not previously been given sufficient means to develop these cognitive skills in the English class. This finding suggests that teachers should consider other classroom practices different than the study of grammatical rules in order to help students speak and think critically in the target language. Learners might develop the ability to use the foreign language more communicatively and purposively when they are assigned tasks that require critical production and analysis.

Although the experience required great efforts for the students to produce meaning in English, they were nevertheless eager to use the foreign language to express their points of views critically about topics closely related to their lives. This result represents a significant change from their former reluctance to speak in the foreign language.

The use of urban legends within the transactional reading approach in the EFL classroom should be considered as a suitable instructional strategy given that

they present authentic language and contain fascinating and provocative contemporary topics appropriate for foreign language learners. With the support of study guides or worksheets, the pedagogical use of urban legends can contribute to the improvement of reading and speaking skills while encouraging learners to become reflective and critical during communicative transactions and the classroom.

References

Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Complete Edition, New York: Longman.

Bell, J. (2005). Doing your research project (4th Ed.). New York: Open University Press.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

Brunvand, J. H. (1981). The vanishing hitchhiker: American urban legends & their meaning. New York:W. W. Norton & Company.

Brunvand, J. (1999). Too good to be true: The colossal book of urban legends. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Carrell, P. L., & Carson, J. G. (1997). Extensive and intensive reading in an EAP setting. English for Specific Purposes, 16(1), 47-60.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cortázar, F. (2008). Esperando a los bárbaros: Leyendas urbanas, rumores e imaginarios sobre la violencia en las ciudades (Waiting for the barbarians: Urban legends, rumors and collective imagination about violence in cities). Nueva época, 9, 59-93.

Dewey, J., & Bentley, A. (1949). Knowing and the known. Boston: Bacon Press.

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Millbrae, CA: The California Academic Press.Facione, P. A. (2007). Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. Millbrae, CA: California Academic Press. Retrieved on April 5thfrom: http://www.insightassessment.com/pdf_files/what%26why2007.pdf%C2%96

Fecho, B., & Amatucci, K. (2008). Spinning out of control: Dialogical transactions in an English classroom. English Teaching: Practice and Critique. 7(1), 5-21.

Heda, J. (1990). Contemporary legend. To be or not to be? Folklore, 101(2), 221- 223.

Johnson, B., & Christensen, L. (2004). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. USA- Pearson Education. Inc.

Koshy, V. (2005). What is action research? Action research for improving practice. London: Paul Chapman Publishing

Merriam, S. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Nosich, G. (2009). Learning to think things through: A guide to critical thinking in the curriculum. Columbus, OH: Pearson.

Parsons, R. D., & Brown, K. (2002). Teacher as reflective practitioner and action research. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2005). Critical thinking competency standards. Foundation for Critical Thinking Press. Retrieved from: http://www.criticalthinking.org/TGS_ files/SAM-CT_competencies_2005.pdf

Perales Escudero, M. D. (2012). Teaching and learning critical reading at a Mexican university: An emergentist case study. Saarbrucken, Germany: Lambert Academic Publishing.

Pineda, C. (2003). Searching for improved EFL classroom environments: The role of critical thinking-related tasks. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia.

Probst, R. E. (1988). ERIC/RCS: Transactional theory in the teaching of literature. Journal of Reading, 31(4), 378- 381.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1995). Literature as exploration (5th ed.). New York: The Modern Language Associations of America.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (2002). La literatura como exploración. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Sternberg, R. J. (1986). Critical thinking: Its nature, measurement, and improvement. Washington, DC: National Institute of Education. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED272882.pdf

Wallace, C. (1992). Critical literacy awareness in the EFL classroom. In N. Fairclough (Ed.), Critical language awareness (pp. 59-92). New York: Longman.

Wallace, C. (1999). Critical language awareness: Key principles for a course in critical reading. Language Awareness, 8(2), 98-110.

Comentarios

3 This article is the result of the research project named “Incorporating American Urban Legends in an EFL Classroom to Enhance Eleventh Graders’ Critical Thinking.” It was supported by the Master Program in the Teaching of Foreign Languages at Universidad Pedagógica Nacional de Colombia.

4 EFL: English as a Foreign Language

5 These urban legends were retrieved from these free sources: http://urbanlegends.about.com/od/accidentsmishaps/a/fatal_ tan.htm and http://www.americanfolklore.net/spooky-stories.htm which were originally compiled by Brunvand’s third collection of urban legends, Curses, Broiled Again! and ‘Too Good to be True’ The colossal book of urban legends.

6 Some of the data have written language mistakes due to students’ natural process of learning the foreign language. Spanish grammar interfered in sentence formation in English like in the case of “state of drunkenness,” words that a student said as he would say in Spanish “estado de embriaguez.” Likewise, the verb kill is in present tense instead of past tense. The data reported here are verbatim samples produced by students.

Métricas

Licencia

Esta publicación tiene licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-No comercial- Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Colombia. El lector podrá leer, copiar y distribuir los contenidos de esta publicación bajo los términos legales de Creative Commons, Colombia.

Para mayor información referirse a http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/co/