DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/23448393.21972Published:

2025-08-01Issue:

Vol. 30 No. 2 (2025): May-AugustSection:

Civil and Environmental EngineeringPhysical and Mechanical Properties of Rattan and Polylactic Acid Biocomposites Printed Using Fused Filament Fabrication

Propiedades físicas y mecánicas de biocompuestos de ratán y ácido poliláctico impresos mediante fabricación por filamentos fundidos

Keywords:

additive manufacturing, biocomposites, fused deposition modeling, mechanical properties, plant fibers (en).Keywords:

manufactura aditiva, biocompuestos, propiedades mecánicas, fibras vegetales, fabricación por filamentos fundidos (es).Downloads

References

R. Asheghi-Oskooee, P. Morsali, T. Farizeh, F. Hemmati, and J. Mohammdi-Roshandeh, “Environmentally friendly approaches for tailoring interfacial adhesion and mechanical performance of biocomposites based on poly(lactic acid)/rice straw,” Int. J. Biol. Macromol., vol. 283, no. 2, art. 137481, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.137481

H. Abdalla, K. P. Fattah, M. Abdallah, and A.K. Tamimi, “Environmental footprint and economics of a full-scale 3D-printed house,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 21, pp. 11978, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111978

H. Ahmad, G. K. Chhipi-Shrestha, K. N. Hewage, and R. Sadiq, “A comprehensive review on construction applications and life cycle sustainability of natural fiber biocomposites,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 23, art. 15905, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142315905

W. Ahmad, S. J. McCormack, and A. Byrne, “Biocomposites for sustainable construction: A review of material properties, applications, research gaps, and contribution to circular economy,” J. Build. Eng., vol. 105, art. 112525, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.112525

J. J. Andrew and H. N. Dhakal, “Sustainable biobased composites for advanced applications: recent trends and future opportunities – a critical review,” Compos. Part C Open, vol. 7, art. 100220, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomc.2021.100220

N. T. Asfaw, R. Absi, B. A. Labouda, and I. El Abbassi, “Assessment of the thermal and mechanical properties of bio-based composite materials for thermal insulation: A review,” J. Build. Eng., vol. 97, art. 110605, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2024.110605

C. Maraveas, “Production of sustainable construction materials using agro-wastes,” J. Mater., vol. 13, no. 262, pp. 2-29, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13020262

Y. Yang et al., “Ultrastrong lightweight nanocellulose-based composite aerogels with robust superhydrophobicity and durable thermal insulation under extremely environment,” Carbohydr. Polym., vol. 323, pp. 121392, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2021.131040

A. Baigarina, E. Shehab, and M.H. Ali, “Construction 3D printing: A critical review and future research directions,” Prog. Addit. Manuf., vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 1–29, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40964-023-00409-8

R. Patel, C. Desai, S. Kushwah, and M. H. Mangrola, “A review article on FDM process parameters in 3D printing for composite materials,” Mater. Today Proc., vol. 60, no.3, pp. 2162–2166, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2022.02.385

S. Kumar et al., “A comprehensive review of FDM printing in sensor applications: Advancements and future perspectives,” J. Manuf. Process., vol. 113, pp. 152–170, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2024.01.030

C. M. Thakar, S. S. Parkhe, A. Jain, K. Phasinam, G. Murugesan, and R. J. M. Ventayen, “3D Printing: Basic principles and applications,” Mater. Today Proc., vol. 51, pp. 842–849, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2021.06.272

A. Al Rashid and M. Koç, “Additive manufacturing for sustainability and circular economy: Needs, challenges, and opportunities for 3D printing of recycled polymeric waste,” Mater. Today Sustain., vol. 24, art. 100529, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtsust.2023.100529

E. Spyridonos, V. Costalonga, J. Petrš, G. Kerekes, V. Schwieger, and H. Dahy, “Enhancing construction accuracy with biocomposites through 3D scanning methodology: Case studies applying pultrusion, 3D printing, and tailored fibre placement,” J. Compos. Mater., vol. 22, art. e04499, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04499

I. Hui, E. Pasquier, A. Solberg, K. Agrenius, J. Håkansson, and G. Chinga-Carrasco, “Biocomposites containing poly(lactic acid) and chitosan for 3D printing – Assessment of mechanical, antibacterial and in vitro biodegradability properties,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 147, pp. 106136, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmbbm.2023.106136

M. Shoeb, L. Kumar, and A. Haleem, “3D printed medical surgical cotton fabric–poly lactic acid biocomposite: A feasibility study,” J. Mater. Res. Technol., vol. 4, pp. 130-146, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.susoc.2023.07.001

M. A. Kacem et al., “Development and 3D printing of PLA bio-composites reinforced with short yucca fibers and enhanced thermal and dynamic mechanical performance,” J. Mater. Res. Technol., vol. 35, pp. 1246–1258, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2025.03.184

D. Fico, D. Rizzo, V. de Carolis, F. Montagna, E. Palumbo, and C. Esposito Corcione, “Development and characterization of sustainable PLA/olive wood waste composites for rehabilitation applications using fused filament fabrication (FFF),” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 56, art. 104673, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104673

H. Anuar et al., “Novel soda lignin/PLA/EPO biocomposite: A promising and sustainable material for 3D printing filament,” Mater. Today Commun., vol. 35, art. 106093, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.106093

K. T. Mekonnen, G. M. Fanta, B. Z. Tilinti, and M. B. Regasa, “Polylactic acid based biocomposite for 3D printing: A review,” Compos. Mater., vol. 8, no.2, pp.57-71, 2024. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.cm.20240802.14

A. K. Trivedi, M. K. Gupta, and H. Singh, “PLA based biocomposites for sustainable products: A review,” Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res., vol. 6, no.4, pp. 382–395, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aiepr.2023.02.002

M. Darsin et al., “The effect of 3D printing filament extrusion process parameters on dimensional accuracy and strength using PLA-brass filaments,” J. Eng. Sci. Technol., vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 145–155, 2023. https://jestec.taylors.edu.my/Special%20Issue%20ICIST%202022_1/ICIST_1_13.pdf

M. Memiş and D. Akgümüş Gök, “Development of Fe-reinforced PLA-based composite filament for 3D printing: Process parameters, mechanical and microstructural characterization,” Ain Shams Eng. J., vol. 16, no. 2, art. 103279, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2025.103279

R. Sultan, M. Skrifvars, and P. Khalili, “Biocomposites containing poly(lactic acid) and chitosan for 3D printing – Assessment of mechanical, antibacterial and in vitro biodegradability properties,” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 4, art. e26617, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26617

N. Gama, S. Magina, A. Ferreira, and A. M. M. V. Barros-Timmons, “Chemically modified bamboo fiber/ABS composites for high-quality additive manufacturing,” Polym. J., vol. 53, no. 12, pp. 1345–1353, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-021-00540-9

H. Ye, Y. He, H. Li, T. You, and F. Xu, “Customized compatibilizer to improve the mechanical properties of polylactic acid/lignin composites via enhanced intermolecular interactions for 3D printing,” Ind. Crop. Prod., vol. 205, art. 117454, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117454

N. K. Kalita et al., “Biodegradation and characterization study of compostable PLA bioplastic containing algae biomass as potential degradation accelerator,” Environ. Challenges, vol.3, art. 100067, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2021.100067

A. K. Trivedi et al., “PLA based biodegradable bio-nanocomposite filaments reinforced with nanocellulose: Development and analysis of properties,” Sci. Rep., vol. 14, art. 23819, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71619-5

J. Mazur et al., “Mechanical properties and biodegradability of samples obtained by 3D printing using FDM technology from PLA filament with by-products,” Sci. Rep., vol. 15, art. 5847, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-89984-0

Standard test methods for direct moisture content measurement of wood and wood-based materials, ASTM D4442-20, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

Plastics - Methods for determining the density of non-cellular plastics - Part 1: Immersion method, liquid pycnometer method and titration method, ISO 1183-1:2019, ISO, Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

Metallic materials - Vickers hardness test - Part 1: Test method, ISO 6507-1:2018, ISO, Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

Standard test method for tensile properties of plastics, ASTM D638-14, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

D. Fico, D. Rizzo, V. de Carolis, F, Montagna, and C. Esposito, “Sustainable polymer composites manufacturing through 3D printing technologies by using recycled polymer and filler,” Polymers, vol.14, art. 3756, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14183756

A. Patti, S. Acierno, G. Cicala, M. Zarrelli, and D. Acierno, “Assessment of recycled PLA-based filament for 3D printing,” Mater. Proc., vol. 7, pp. 16, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/IOCPS2021-11209

C. Pascual-González, M. Iragi, A. Fernández, J. P. Fernández-Blázquez, L. Aretxabaleta, and C. S. Lopes, “An approach to analyse the factors behind the micromechanical response of 3D-printed composites,” Compos. Part B Eng., vol. 186, art. 107822, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.107820

V. Reddy, O. Flys, A. Chaparala, C. E. Berrimi, V. Amogh, and B. G. Rosen, “Study on surface texture of fused deposition modeling,” Procedia Manuf., vol. 25, pp. 389-396, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2018.06.108

M. Eryildiz “Effect of build orientation on mechanical behaviour and build time of FDM 3D-printed PLA parts: An experimental investigation,” European Mech. Sci., vol. 5, pp.116-120, 2021. https://doi.org/10.26701/ems. 881254

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 3 de noviembre de 2024; Aceptado: 26 de junio de 2025

Abstract

Context:

The use of alternative materials in construction requires the implementation of new methods that allow addressing the problems associated with the manufacture of traditional composite materials. In recent years, additive manufacturing techniques have attracted the attention of entrepreneurs and researchers due to its ease in processing complex designs and its low processing times. However, there is little information about the mechanical performance of composites obtained from the processing of biopolymer filaments reinforced with plant fibers.

Method:

We evaluated the mechanical behavior of 3D-printed biocomposites subjected to axial tension loads. For the experimental design, filaments were constructed using 90% polylactic acid granules and 10% pulverized rattan fibers. The properties of the filaments were analyzed through microscopy, density, thermogravimetry, roughness, and hardness tests. The specimens were printed according to the dimensions specified in ASTM D638, and the effect of infill density and printing orientation on their physical and mechanical properties was analyzed. A statistical analysis was carried out in order to formulate equations allow predicting the behavior of the material based on the printing parameters considered.

Results:

The obtained filaments were characterized and compared against their unreinforced counterparts. The specimens were printed using the fused deposition method. The effect of the printing parameters on the physical and mechanical properties of the stressed biocomposite was determined, and the impact of the studied variables was analyzed using a central composite design.

Conclusions:

The surface roughness of the samples increased with the printing orientation and decreased as the infill density increased. Hardness and tensile strength increased significantly with increasing infill density, and they decreased with an increasing printing angle. The probes printed with 80% infill showed a notable increase in rigidity.

Keywords:

additive manufacturing, biocomposites, fused filament fabrication, mechanical properties, plant fibers.Resumen

Contexto:

El uso de materiales alternativos en la construcción requiere implementar nuevos métodos que permitan enfrentar los problemas asociados a la fabricación de materiales compuestos tradicionales. En los últimos, años las técnicas de fabricación aditiva han llamado la atención de emprendedores e investigadores debido a su facilidad para procesar diseños complejos y sus tiempos de procesamiento reducidos. Sin embargo, existe poca información sobre el desempeño mecánico de los compuestos obtenidos del procesamiento de filamentos de biopolímeros reforzados con fibras vegetales.

Método:

Se evaluó el comportamiento mecánico de biocompuestos impresos en 3D sometidos a cargas de tensión axial. Para el diseño experimental, se elaboraron filamentos utilizando 90% de gránulos de ácido poliláctico y 10% de fibras pulverizadas de ratán. Las propiedades de los filamentos se analizaron mediante ensayos de microscopía, densidad, termogravimetría, rugosidad y dureza. Las probetas se imprimieron de acuerdo con las dimensiones especificadas en ASTMD 638, y se analizó el efecto de la densidad de relleno y la orientación de impresión sobre sus propiedades físicas y mecánicas. Se realizó un análisis estadístico orientado a formular ecuaciones que permitieran predecir el comportamiento del material con base en los parámetros de impresión considerados.

Resultados:

Los filamentos obtenidos fueron caracterizados y comparados con sus contrapartes no reforzadas. Las probetas se imprimieron mediante el método de deposición fundida. Se determinó el efecto de los parámetros de impresión sobre las propiedades físicas y mecánicas del biocompuesto sometido a esfuerzo, y se analizó el impacto de las variables estudiadas mediante un diseño compuesto central.

Conclusiones:

La rugosidad superficial de las muestras aumentó con la orientación de impresión y disminuyó a medida que aumentó la densidad de relleno. La dureza y la resistencia a la tracción aumentaron significativamente con el incremento de la densidad de relleno y disminuyeron con el aumento del ángulo de impresión. Las probetas impresas con un 80% de relleno mostraron un incremento notable en su rigidez

Palabras clave:

manufactura aditiva, biocompuestos, fabricación por filamentos fundidos, propiedades mecánicas, fibras vegetales.Introduction

The concern for encouraging sustainable development in various sectors of the industry has promoted the study, design, and characterization of new materials that contribute to mitigating the environmental impact associated with the use of traditional materials derived from the processing of petroleum-derived resources, thereby reducing the greenhouse gas emissions caused by the technological processes applied in their production 1,2. In this sense, and in line with the Sustainable Development Goals, biocomposite materials have emerged as a new alternative that allows replacing conventional solutions, reducing the use of inputs, and minimizing the carbon footprint 1-5.

According to 4, biocomposite materials offer some advantages over conventional composite materials, including reduced CO2 emissions, biodegradability, low toxicity, and energy efficiency. However, the use of biocomposites in the construction sector may be limited by factors such as strength, stiffness under humid conditions, incompatibility between the constituent materials, and variability in the composition of the plant fibers used as reinforcement, which makes it difficult to standardize the properties of the materials 5 8.

Due to its innovative nature, additive manufacturing (or 3D printing) has become important in the design, manufacture, and characterization of biocomposite materials 9(13. Among the different additive manufacturing techniques available, fused filament fabrication (FFF) stands out, which consists of the layer-by-layer deposition of a thermoplastic polymer. The filament is heated and extruded through a nozzle, shaping the object in a controlled manner. Through this printing method, it is possible to reduce fabrication cycle times and thus minimize production costs. Additionally, this process allows reducing waste material, making it possible to modify the microstructure of each of the composite’s layers, which provides the finished product with added value 10. Furthermore, 3D printing offers flexibility to generate complex structures that satisfy the design requirements of various industrial sectors 13-16.

The use of plant fibers as reinforcement for polymeric filaments has increased in recent years 17. Its main advantages include wide availability, low cost, good mechanical behavior, and biodegradability. From a technical and environmental perspective, this makes them a viable option for the development of new, alternative materials that can be applied in various fields of engineering, e.g., civil construction 18,19.

Due to its ease of processing, one of the biopolymers most commonly used as a biofilament matrix is polylactic acid (PLA), which is processed through the chemical sintering of sugars obtained from the biomass of plants such as corn, cassava, and sugar cane 20,21. This material is known for its low toxicity, biodegradability, high hardness and stiffness, and good resistance to most common solvents 21.

According to 22, some parameters, such as the extrusion temperature and speed, can affect the properties of these filaments. In addition, other parameters like the selection of raw materials (fiber and polymer) and premixing proportions and techniques can influence the final quality (roughness, hardness, porosity, and resistance) of the biocomposite filaments produced by screw extruders. Despite several published studies, to date, there are some research gaps regarding the optimization of these properties for specific applications 23.

Recent studies have shown that fiber content, surface treatments, and the use of compatibilizing agents can affect the strength and stiffness of biofilaments 24-26. 24 analyzed the physical and mechanical properties of specimens printed with polypropylene reinforced with different hemp fiber contents. These authors demonstrated that flexural strength, tensile strength, and absorption capacity vary significantly depending on the fiber content and printing method used. In addition, 25 analyzed the effect of surface modification on bamboo fibers used as reinforcement in acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) filaments. As a result of the treatment, the authors reported that it was possible to improve both the filament morphology and the mechanical properties of the printed specimens.

26 examined the effect of a lignin-based compatibilizing agent on the tensile strength, elongation, and toughness of polylactic acid/lignin composites, attributing the improvements to enhanced intermolecular interactions for 3D printing applications.

Other studies have focused on evaluating the degradation and sustainability of PLA-printed materials. For instance, 27 analyzed the degradation of PLA biocomposites reinforced with algal biomass under abiotic and thermophilic composting conditions. This study showed that the addition of algal biomass increased the biodegradability of PLA, an effect attributed to the high nitrogen content in the biomass, which promoted microbial growth.

28 developed PLA-based bionanocomposites reinforced with crystalline nanocellulose in order to improve the mechanical and thermal properties of 3D-printed PLA products. This reinforcement enhanced the crystallinity and the thermal, mechanical, and rheological properties of PLA, demonstrating that small amounts of crystalline nanocellulose can optimize the performance of 3D printing filaments 28.

In addition, 29 investigated the effect of adding carrot pulp and ground walnut shells to PLA, aiming to evaluate how these additives influence the mechanical properties and biodegradability of FFF-printed parts. The study showed that these plant-based additives can improve the flexural strength and biodegradability of the biocomposite, although they reduce its fracture toughness.

Despite the advances reported in the literature, the use of filaments made from the combination of plant-based materials as raw input in 3D printing processes still requires a deeper understanding of their mechanical behavior, as well as an analysis of the design parameters that influence their quality and performance. This study evaluated the density, roughness, hardness, strength, and stiffness of biocomposites printed using biofilaments reinforced with 10% pulverized plant fibers. Due to their biodegradability, renewability, and ease of processing, PLA granules were used for filament fabrication. In addition, rattan fibers (a plant-based material that has been scarcely explored in the development of 3Dprinting filaments) were used as reinforcement. These fibers were obtained from waste generated by Bambú y Guaduas de Colombia, a company dedicated to the production of furniture and handicrafts. This selection contributes to reducing solid waste, promotes the use of renewable resources, and aligns with the principles of sustainable development and the circular economy.

As an emerging technology, 3D printing was chosen for the composite. The effect of several design parameters was evaluated through statistical analysis. Equations were formulated to predict the material’s behavior based on the parameters used during 3D printing. The novelty of this study lies in the development and characterization of PLA-based filaments reinforced with rattan fibers, whose application in additive manufacturing has not been extensively explored. Furthermore, this study provides insights into the way in which printing parameters affect the mechanical behavior of these biocomposites. Additionally, obtaining prediction equations can contribute to standardizing and optimizing the properties of printed biocomposites.

Materials and methods

To produce the filaments, commercial PLA granules and 30 cm long, 1 cm wide rattan strips were used. We employed waste fibers donated by Bambú y Guaduas de Colombia. To obtain the reinforcing material, the strips were crushed, dried in an oven at 105 °C, pulverized, and then sieved using a 45 µm mesh. The drying temperature was selected in accordance with the recommendations of ASTM 4442-20 30. We used Ingeo D4032, a biopolymer manufactured by Nature Works LLC in the USA. The pellets were dried for four hours at 80 °C before mixing. Two types of filaments were produced for comparison: pure PLA filaments (PLA-S) and PLA-based composite filaments (PLA-R). The latter were prepared by blending 90% PLA with 10% pulverized rattan fibers. The pulverized rattan fibers were manually mixed with PLA pellets. All filaments, with a diameter of 1.75 mm, were extruded with a single-screw extruder at 180 °C and a feed rate of 50 mm/s. After extrusion, the filaments were stored in a dry environment to prevent moisture absorption.

To evaluate the quality of the filaments, physical and mechanical characterization tests were carried out. A description of the procedures is presented below.

-

Morphology. The surface of the filaments was analyzed using a Tescan Vega3 scanning electron microscope. The acceleration voltage of the electron beam was 20 kV, and the working distance was 14.9 mm. To improve electrical conductivity, the filaments were previously metallized. We obtained images with a magnification of 800x.

-

Density. Samples measuring 5 cm in length and 1.75 mm in diameter were prepared. For each type of filament, ten samples were characterized. The test was carried out using a pycnometer, following the procedures described in method B of ISO 1183-1:2019 31.

-

Roughness. Samples of 10 cm in length were prepared. A PCERT 1200 instrument was used for the test. Eight readings were taken for each filament. Based on the results, the average roughness for each type of filament was calculated.

-

Hardness. A FALCON 400G2 durometer was used to determine the Vickers microhardness. The applied load was 50 g. The test was carried out while following the recommendations of ISO 6507-1:2018 32 and consisted of measuring the diagonal lengths of the indentation produced by a pyramidal diamond indenter.

-

Thermal analysis. Thermogravimetric analysis was conducted using an SDT Q600 V20.9 Build 20. Thermal tests were carried out in alumina containers, in a synthetic air atmosphere, at a Flow rate of 60 mL/min and a heating rate of 5 °C/min.

-

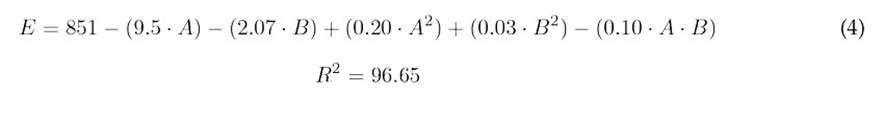

Tensile strength. Samples measuring 1.75 mm in diameter and 7 cm in length were prepared. The tests were carried out using a WP 300 universal testing machine with a load capacity of 20 kN. To f ix the samples to the jaws of the equipment, trapezoidal pieces were designed and glued to the ends of the filaments. For each type of filament, ten samples were tested. This is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Filament tensile test

For the CAD model, the dimensions established in ASTM 638 for type-V specimens were adopted 33. Specimens with an infill density of 20, 40, and 80% were printed. As a filling pattern, a gyroid-type element was established. To evaluate the effect of printing orientation on the properties of the biocomposite, angles of 0° (horizontal) , 45° (diagonal), and 90° (vertical) were used. The orientation diagram is presented in Fig. 2. We employed an Ender 5 S1 printer with a 0.4 mm brass nozzle at a temperature of 205 °C. The print bed temperature was 60 °C, and the print speed was set at 80 mm/s. Theprint layer height was 0.3 mm.Thislayerthickness allows for faster printing without compromising mechanical strength.

Figure 2: Orientation diagram

We evaluated the effect of printing parameters (fill density and print orientation) on the physical (density, roughness, and hardness) and mechanical properties (strength and elastic modulus) of the specimens printed with PLA-R filaments. We used a commercial statistical analysis software, implementing a central design composed of two factors, with 14 runs and five replications.The statistical analysis yielded equations that allow predicting the properties of the biocomposite based on the design variables.

Results and discussion

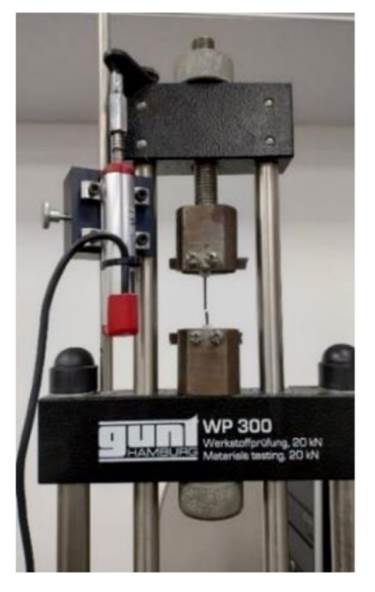

To analyze the quality of the filaments, 800x micrographs of the PLA-R and PLA-S filaments were obtained. These are presented in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Filament micrographs: a) PLA-R, b) PLA-S

In Fig. 3a, the presence of randomly distributed fibers encapsulated by the polymeric matrix can be observed. Additionally, there are voids at the interface between the biopolymeric matrix and the reinforcing fiber. The PLA-R filaments have an irregular appearance, with some discontinuities. These f indings can be attributed to the lack of homogeneity in the distribution of fibers during extrusion. On the other hand, as shown in Fig. 3b, the PLA-S filaments have a smooth and more homogeneous appearance.

Thedensity, roughness, and hardness of the filaments were determined by following the procedures described in Section 2 for PLA-R and PLA-S, the results of which are presented in Table I. Note that, despite the voids generated inside the filament during extrusion, the addition of plant fibers did not cause significant density changes. However, the roughness of the PLA-R filaments increased by approximately 40%. According to 34, the smooth surface of biopolymeric filaments such as PLA-S can be associated with a greater fragility. This is consistent with the observed increase in the Vickers microhardness of the PLA-R filaments (approximately 17%). It should be noted that the plant fibers act as reinforcement for the PLA, which contributes to increasing the hardness of the filament. On the other hand, since this is a natural material, a product with a less homogeneousandroughertextureisobtained during extrusion.

Table I: Physical properties of the filaments

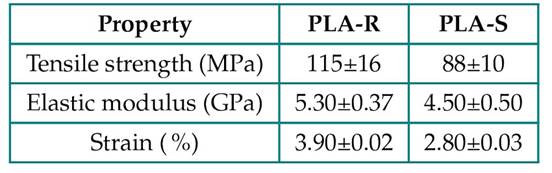

As shownin Table II, the mechanical properties of the filaments were also determined.

Table II: Mechanical properties of the filaments

Table II shows an increase of approximately 30% in the tensile strength of the PLA-R filaments, as well as an increase of 17% in their elastic modulus. Additionally, their percentage of deformation increased by 40%.

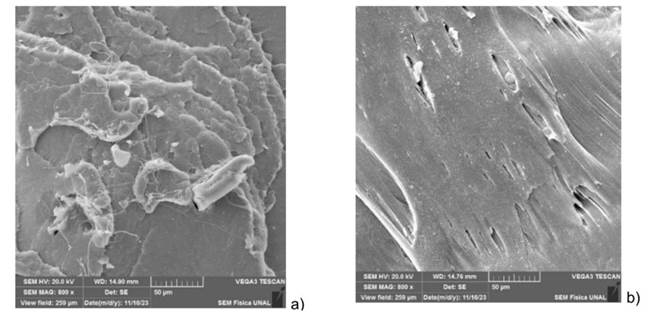

The results of the thermal analysis are presented in Fig. 4. Regarding the thermogravimetry test, it was observed that the addition of pulverized rattan fibers does not significantly affect the thermal behavior of the filaments. Differences of less than 1% can be observed in Ti, Toi, Tmax, and Tb. These results are consistent with those presented by 35 for pure PLA specimens. On the other hand, for PLA-R, a decrease of 11% can be observed in the temperature at which the final combustion of the material occurs (Tof), which may be associated with weight loss and the depolymerization of the rattan f ibers 36.

Figure 4: TGA results

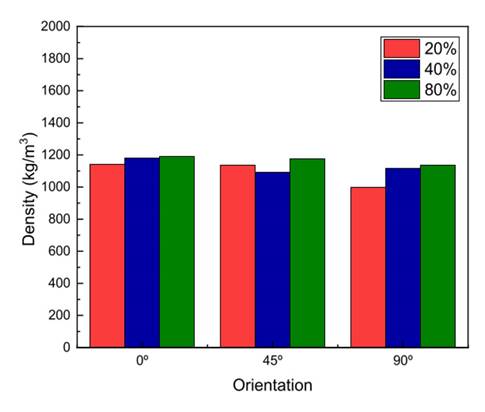

Fig. 5 shows the effect of infill density and printing orientation on the density of specimens printed using PLA-R filaments. As for the latter, variations of less than 15% are observed. From the results, it can be concluded that the orientation of the printing layers did not significantly affect the density of the material. Similar results were observed when increasing the infill percentage from 20 to 80% in specimens printed at 0°, 45°, and 90°. Because the density of the material depends not only on the infill density used but also on the configuration (fill type), printing completely dense parts may be unnecessary and represent a waste of material and increased printing times.

Figure 5: Effect of printing parameters on density

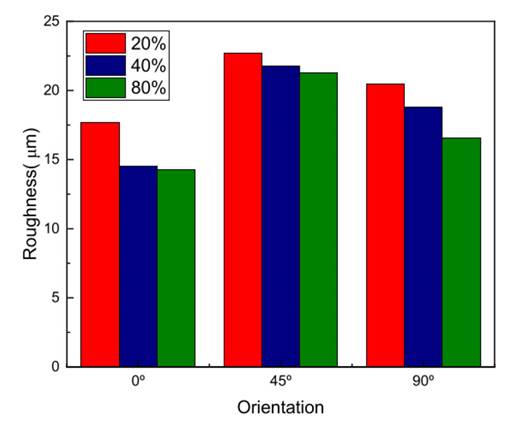

Surface roughness is considered to be one of the main quality indicators of elements created through additive manufacturing. Fig. 6 presents the effect of infill density and printing orientation on the roughness of the specimens printed using PLA-R filaments. Note that the roughness decreases as the filling density increases. On the other hand, the orientation of the specimens on the printing bed influences the surface texture of the material. Similar results were reported by 37, confirming that the roughness of the pieces increases with the printing angle.

Figure 6: Effect of printing parameters on roughness

Another important parameter for evaluating the quality of the material is microhardness. Fig. 7 shows the effect of the analyzed printing parameters on the Vickers hardness of the printed specimens. According to the results, different filling densities entail differences in the hardness of the printed specimens. A high density leads to a low number of voids and, therefore, to high hardness values. The reported microhardness was between 16.1 and 21.55 HV for specimens printed at 0°. However, no significant variations were observed in specimens printed at 45° and 90°.

Figure 7: Effect of printing parameters on microhardness

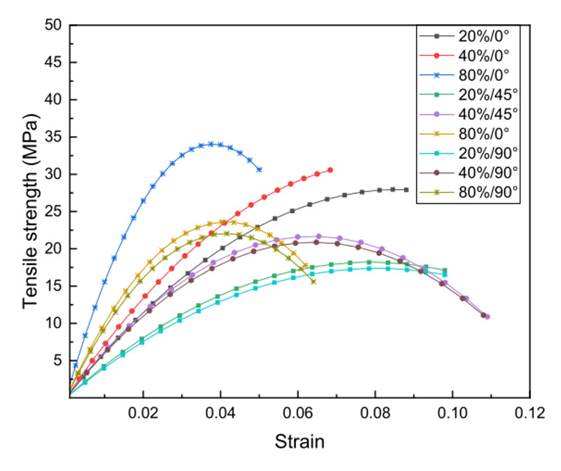

The effect of the infill density and the printing orientation on the specimens’ tensile strength and elastic modulus is shown in Figs. 8and 9, respectively. Note that, by increasing the infill density from 20 to 80%, a 20% increase in the tensile strength of the samples printed at 0° is obtained, in addition to a significant increase in their elastic modulus (1617 MPa). A gyroid-type fill pattern contributes to the strength and stiffness of the material since it maintains a constant curvature in all directions. However, the specimens printed at 45° and 90° exhibited a reduction of up to 50% in their maximum tensile strength. Similar results were obtained by 38, demonstrating that a material performs better if the printed element is oriented along the direction in which the load is applied.

Figure 8: Effect of printing parameters on tensile strength

Figure 9: Effect of printing parameters on elastic modules

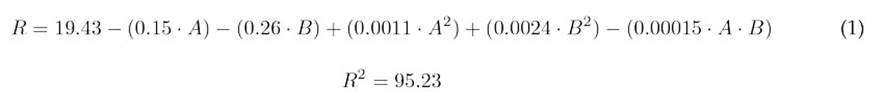

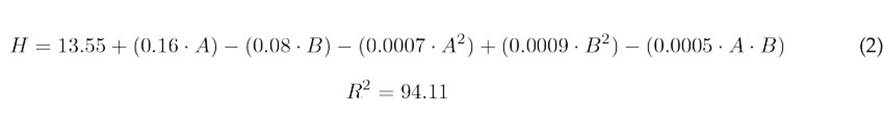

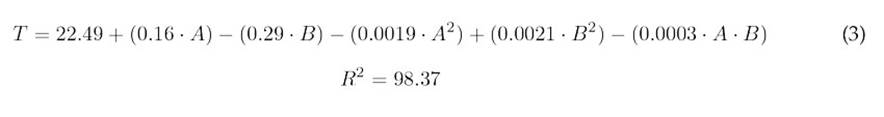

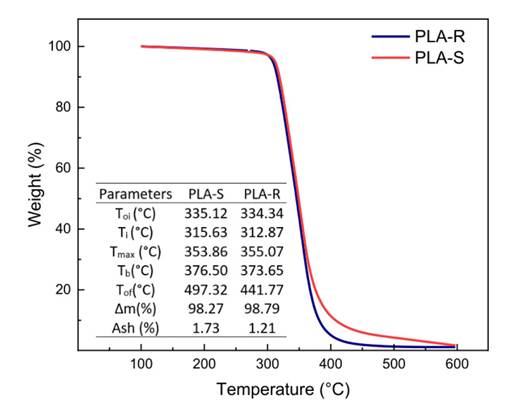

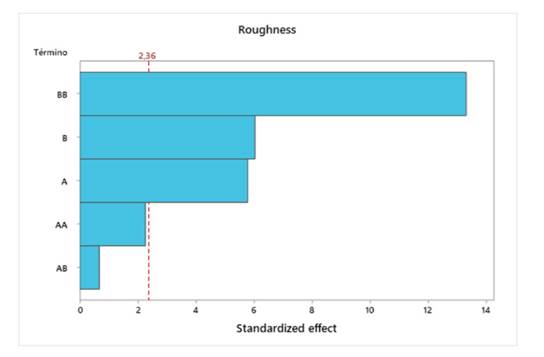

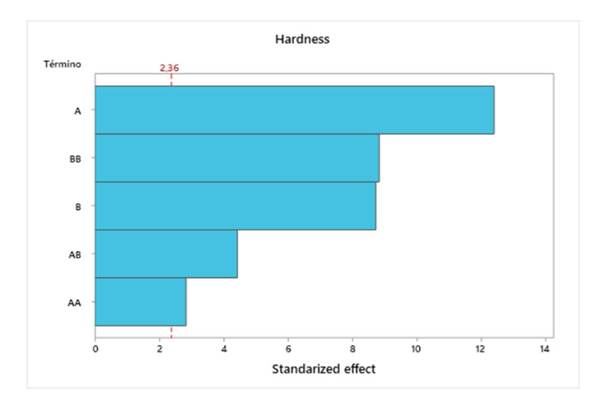

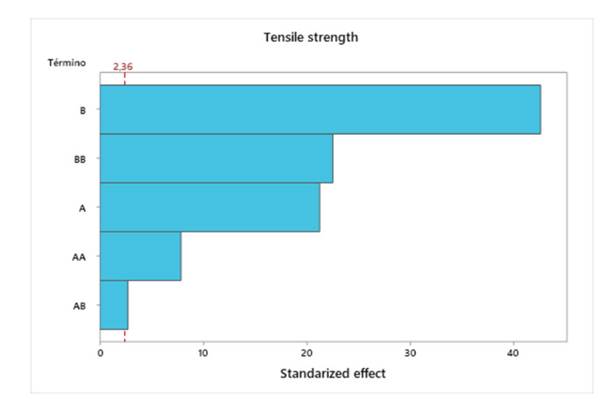

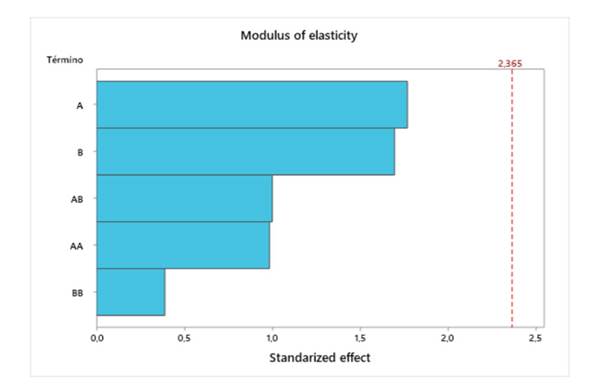

The effect of the aforementioned parameters and their interaction was evaluated by analyzing the response surface. A Pareto diagram was constructed in order to visualize the influence of the parameters on the roughness, hardness, tensile strength, and elastic modulus of the specimens. The results are shown in Figs. 10, 11, 12, and 13. Here, the labels represent the factors and their interactions: A corresponds to the infill density (%), B to the printing orientation, AA to the second-level effect of factor A, BB to the second-level effect of factor B, and AB to the interaction between the infill density and the printing orientation. It was observed that these parameters significantly affect the hardness and tensile strength of the samples printed through the fused deposition of plant filaments. In the case of roughness, the interaction between the studied variables produced no visible effect, nor was the elastic modulus of the samples tested for tension significantly affected.

Figure 10: Pareto diagram used to evaluate the effect of the design variables on roughness

Figure 11: Pareto diagram used to evaluate the effect of the design variables on hardness

Figure 12: Pareto diagram used to evaluate the effect of the design variables on tensile strength

Figure 13: Pareto diagram used to evaluate the effect of the design variables on the elastic modulus

Pareto diagram used to evaluate the effect of the design variables on tensile strength

where:

-

A is the infill density in%

-

B is the printing orientation in ◦

-

R is the roughness in µm

-

H isthe hardness in HV

-

T is the tensile strength in MPa

-

E is the elastic modulus in MPa

-

R2 is the coefficient of determination

Conclusions

This work evaluated the physical and mechanical properties of printed specimens elaborated via FFF, using 90% PLA and 10%pulverized rattan fibers. The main findings are presented below.

The presence of micro-voids caused by the lack of homogeneity in the distribution of the fibers during extrusion did not affect the physical and mechanical properties of the plant filaments.

PLA-R showed a 42.3% increase in surface roughness and a 13.6% increase in hardness. These results indicate that the addition of rattan fibers affects both the surface texture and the hardness of the filaments.The PLA-R filaments showed a 30.7% increase in their tensile strength, a 17.8% increase in their elastic modulus, and a 39.3% increase in their maximum strain, demonstrating that the incorporation of pulverized rattan fibers as reinforcement contributes to improved filament strength, stiffness, and ductility.

The surface roughness of the printed samples increased by up to 35% with the printing orientation, and it decreased by 17% as the infill density increased.

Hardness and tensile strength increased significantly as the infill density increased, and they decreased as the printing angle increased from 0° to 90°. The specimens printed with 80% infill showed a notable increase in rigidity. However, the corresponding Pareto diagram does not identify the effect of the studied variables and their interaction on the elastic modulus.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement

This paper is a derivative product of the project (INV-ING-3788) financed by the Vicerectory of Research of Universidad Militar Nueva Granada-validity (2023).

References

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Martha Lissette Sánchez-Cruz, Luz Yolanda Morales-Martin, Gil Capote Rodríguez

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

From the edition of the V23N3 of year 2018 forward, the Creative Commons License "Attribution-Non-Commercial - No Derivative Works " is changed to the following:

Attribution - Non-Commercial - Share the same: this license allows others to distribute, remix, retouch, and create from your work in a non-commercial way, as long as they give you credit and license their new creations under the same conditions.

2.jpg)