DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/23448393.22162Publicado:

2024-09-19Número:

Vol. 29 Núm. 3 (2024): Septiembre-diciembreSección:

Ingeniería Eléctrica, Electrónica y TelecomunicacionesPassivity-Based Model-Predictive Control for the Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machine

Control predictivo basado en pasividad para la máquina síncrona de imanes permanentes

Palabras clave:

Passivity-based control, Permanent-Magnet synchronous machines, Model Predictive control, Stability (en).Palabras clave:

Control basado en pasividad, Máquinas síncronas de imanes permanentes, Control predictivo de modelos, Estabilidad (es).Descargas

Referencias

V. Yaramasu, B. Wu, P. C. Sen, S. Kouro, and M. Narimani, "High-power wind energy conversion systems: State-of-the-art and emerging technologies," Proc. IEEE, vol. 103, no. 5, pp. 740-788, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2014.2378692

I. Sami, N. Ullah, S. M. Muyeen, K. Techato, M. S. Chowdhury, and J.-S. Ro, "Control methods for standalone and grid connected micro-hydro power plants with synthetic inertia frequency support: A comprehensive review," IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 176313-176329, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3026492

D. Ramirez, J. P. Bartolome, S. Martinez, L. C. Herrero, and M. Blanco, "Emulation of an OWC ocean energy plant with PMSG and irregular wave model," IEEE Trans. Sustainable Energy, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 1515-1523, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSTE.2015.2455333

R. S. Kaarthik, K. S. Amitkumar, and P. Pillay, "Emulation of a permanent-magnet synchronous generator in real-time using power hardware-in-the-loop," IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 474-482, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1109/TTE.2017.2778149

K.-W. Hu and C.-M. Liaw, "Incorporated operation control of DC microgrid and electric vehicle," IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron., vol. 63, no. 1, pp. 202-215, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2015.2480750

Y. Belkhier et al., "Interconnection and damping assignment passivity-based non-linear observer control for efficiency maximization of permanent magnet synchronous motor," Energy Rep., vol. 8, pp. 1350-1361, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2021.12.057

X. Liu, H. Yu, J. Yu, and Y. Zhao, "A novel speed control method based on port-controlled Hamiltonian and disturbance observer for PMSM drives," IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 111115-111123, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2934987

R. Ortega and E. Garcia-Canseco, "Interconnection and damping assignment passivity-based control: A survey," Eur. J. Control, vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 432-450, 2004. https://doi.org/10.3166/ejc.10.432-450

S. Vazquez et al., "Model predictive control: A review of its applications in power electronics," IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 16-31, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIE.2013.2290138

M. Schwenzer, M. Ay, T. Bergs, and D. Abel, "Review on model predictive control: An engineering perspective," Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol., vol. 117, no. 5, pp. 1327-1349, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-021-07682-3

M. Khanchoul, M. Hilairet, and D. Normand-Cyrot, "IDA-PBC under sampling for torque control of PMSM," IFAC Proc. Volumes, vol. 46, no. 11, pp. 15-20, 2013. https://doi.org/10.3182/20130703-3-FR-4038.00059

W. Gil-Gonzalez, A. Garces, and O. B. Fosso, "Passivity-based control for small hydro-power generation with PMSG and VSC," IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 153001-153010, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3018027

W. Wang, H. Shen, L. Hou, and H. Gu, "H∞ robust control of permanent magnet synchronous motor based on PCHD," IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 49150-49156, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2893243

F. Ramirez-Leyva, E. Peralta-Sanchez, J. Vasquez-Sanjuan, and F. Trujillo-Romero, "Passivity-based speed control for permanent magnet motors," Procedia Technol., vol. 7, pp. 215-222, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2013.04.027

M. Aijaz and K. Sakthivel, "Neural network based voltage source converter for power management of hybrid energy system," in Proc. 2024 Third Int. Conf. Intelligent Tech. Control, Optimization Signal Process. (INCOS), pp. 1-7, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1109/INCOS59338.2024.10527574

Y. Cao and J. Guo, "Research on characteristic model-based adaptive control of high-speed permanent magnet synchronous motor with time delay," Int. J. Control Autom. Syst., vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 460-474, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12555-021-0968-1

Y. Zhang et al., "Backstepping control of permanent magnet synchronous motors based on load adaptive fuzzy parameter online tuning," J. Power Electron., pp. 1-12, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43236-024-00790-9

Z. Yin et al., "Plant-physics-guided neural network control for permanent magnet synchronous motors," IEEE J. Sel. Topics Signal Process., pp. 1-14, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTSP.2024.3430822

W. Sun et al., "Research on efficiency of permanent-magnet synchronous motor based on adaptive algorithm of fuzzy control," Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 3, p. 1253, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16031253

K. Li, J. Ding, X. Sun, and X. Tian, "Overview of sliding mode control technology for permanent magnet synchronous motor system," IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 71685-71704, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3402983

Z. Huang et al., "Improved active disturbance rejection control for permanent magnet synchronous motor," Electronics, vol. 13, no. 15, p. 3023, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13153023

J. Zhu et al., "Model predictive current control based on hybrid control set for permanent magnet synchronous motor drives," IET Power Electron., vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 450-462, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1049/pel2.12657

D. B. Tchoumtcha, C. T. S. Dagang, and G. Kenne, "Synergetic control for stand-alone permanent magnet synchronous generator driven by variable wind turbine," Int. J. Dyn. Control, pp. 1-15, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40435-024-01384-w

L. Chen et al., "Sensorless control of permanent magnet synchronous motor based on adaptive enhanced extended state observer," Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl., vol. 52, pp. 4303-4322, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1002/cta.3983

F. Xiao et al., "A finite control set model predictive direct speed controller for PMSM application with improved parameter robustness," Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst., vol. 143, p. 108509, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2022.108509.

Y. Wang et al., "Adaptive observer-based current constraint control for permanent magnet synchronous motors," IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 91415-91426, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3289586

M. Graf, L. Otava, and L. Buchta, "Simple linearization approach for mpc design for small pmsm with field weakening performance," IFAC-PapersOnLine, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 159-164, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2015.07.025

Y. Li, C. Zhao, Y. Zhou, and Y. Qin, "Model predictive torque control of pmsm based on data drive," Energy Reports, vol. 6, pp. 1370-1376, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyr.2020.11.019

T. Raff, C. Ebenbauer, and P. Allgower, Nonlinear Model Predictive Control: A Passivity-Based Approach. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer, 2007.

L. T. Biegler, "A perspective on nonlinear model predictive control," Korean J. Chem. Eng., vol. 38, pp. 1317-1332, Jul 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11814-021-0791-7

P. Falugi, "Model predictive control: a passive scheme," IFAC Proc. Vol., vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 1017-1022, 2014. https://doi.org/10.3182/20140824-6-ZA-1003.02165

A. Tahirovic and G. Magnani, "Some Limitations and Real-Time Implementation," in Nonlinear Model Predictive Control, London, UK: Springer, 2013, pp. 41-51. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-5049-7_4

A. van der Schaft and D. Jeltsema, Port-Hamiltonian Systems Theory: An Introductory Overview, vol. 1. London, UK: Now, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1561/9781601987877

D. Mayne, J. Rawlings, C. Rao, and P. Scokaert, "Constrained model predictive control: Stability and optimality," Automatica, vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 789-814, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-1098(99)00214-9

W. Haddad and V. Chellaboina, Nonlinear Dynamical Systems and Control: A Lyapunov-Based Approach, 2nd ed., Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton Univ. Press, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400841042

J. A. E. Andersson, J. Gillis, G. Horn, J. B. Rawlings, and M. Diehl, "CasADi - A software framework for nonlinear optimization and optimal control," Math. Program. Comput., vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1-36, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12532-018-0139-4

Cómo citar

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Descargar cita

Recibido: 14 de mayo de 2024; Aceptado: 10 de agosto de 2024

Abstract

Context:

This study focuses on advanced control techniques for permanent magnet synchronous machines (PMSMs), which are crucial in various industrial applications due to their efficiency and precise control requirements. Passivity-based control methods offer stability and performance, addressing these challenges effectively.

Method:

A passivity-based model predictive control (MPC) is proposed, integrating port-Hamiltonian representation with optimization. Stability theorems are theoretically explored. The simulation evaluates the performance of our proposal under different prediction horizons and stability constraints.

Results:

The proposed MPC is analyzed across several horizons, both including and excluding passivity and exponential stability constraints. Conclusions: This study presents a novel passivity-based MPC approach for PMSM speed regulation, highlighting the importance of stability constraints. Future research should extend this controller to synchronous machines in power systems and voltage source converters.

Keywords:

passivity-based control, Permanent-magnet synchronous machines, model-predictive control, stability.Resumen

Contexto:

Este estudio se centra en técnicas avanzadas de control para máquinas síncronas de imanes permanentes (PMSM), fundamentales en diversas aplicaciones industriales debido a su eficiencia y requisitos de control precisos. Los métodos de control basados en pasividad ofrecen estabilidad y rendimiento y permiten abordar eficazmente estos desafíos.

Métodos:

Se propone un control predictivo basado pasividad (MPC), integrando la representación port-Hamiltoniana con la optimización. Se exploran teoremas de estabilidad teóricamente. La simulación evalúa el rendimiento de nuestra propuesta bajo diferentes horizontes de predicción y restricciones de estabilidad.

Resultados:

El MPC propuesto se analiza en varios horizontes, incluyendo y excluyendo restricciones de pasividad y estabilidad exponencial.

Conclusiones:

Este estudio presenta un enfoque novedoso de MPC basado en pasividad para la regulación de velocidad de PMSM, destacando la importancia de las restricciones de estabilidad. La investigación futura debería extender este controlador a máquinas síncronas en sistemas de energía y convertidores de fuente de voltaje.

Palabras clave:

control basado en pasividad, máquinas síncronas de imanes permanentes, control predictivo basado en el modelo, estabilidad.Introduction

Motivation

The permanent magnet synchronous machine (PMSM) is a classic technology that has been revitalized in recent years. It is commonly used in wind energy 1, hydro-power generation 2, wave and tidal energy systems 3, electric vehicles 4 and microgrids 5, among other industrial applications. The dynamics of this machine are described by nonlinear equations that are sensitive to unknown external disturbances, which complicates the control task. Therefore, nonlinear controls are required to adjust for nonlinearities and drawbacks 6.

A PMSM can be represented in the framework of port-Hamiltonian systems 7. This characteristic is convenient for the use of passivity-based controls, which ensure stability and maintain the natural dynamics of the physical system. However, passivity-based controls may be surpassed by conventional ones in terms of efficiency 8.

On the other hand, model-predictive control has become popular in industrial applications, given its advantages in terms of performance 9. In addition, it is a nonlinear control capable of introducing constraints into the model 10. However, the stability and structural properties of physical systems may be compromised in the design stage 11. Therefore, there is a research gap regarding the interaction between passivity-based and model-predictive control in practical applications such as the speed regulation of PMSMs.

State of the art

Passivity-based control has been used to control PMSMs in different applications. In 12, a control for small hydro-power generation plant was proposed. The control was stable and preserved structural properties during closed-loop operation. An H∞ robust control based on the Hamilton-Jacobi inequality was presented in 13. This control exhibited a port-controlled Hamiltonian structure with the dissipation form. In addition, a passivity-based control for the speed regulation of a permanent magnet synchronous motor was presented in 14. Experimental results showed that the control was easy to program, as it was reduced to a set of algebraic equations. In all these cases, the goal was the stability and practical implementation of the control, but they lacked a profound study of the improvement in performance.

In recent years, various advanced nonlinear control topologies have been developed to enhance the speed regulation performance of PMSMs across different applications. These approaches include artificial neural network control 15, adaptive control 16, backstepping-fuzzy control 17, neural network control 18, adaptive fuzzy logic control 19, sliding mode control 20, active disturbance rejection control 21, predictive current control 22, synergetic control 23, and adaptive extended-state observer control 24. While recent advancements in nonlinear control techniques (15, 24) have shown promising results in improving the speed regulation performance of PMSMs, each approach also comes with its own set of limitations. For instance, neural network control may require extensive training data and computational resources, while sliding mode control can be sensitive to uncertainties and parameter variations. Adaptive control strategies, although versatile, may face challenges in ensuring robustness across all operating conditions. Additionally, disturbance rejection or synergetic control methods often rely on accurate models, which can be restrictive in practical implementations.

On the other hand, model-predictive control is another nonlinear technique that has been used for controlling PMSMs. For instance, in 25, a finite control set model-predictive control was suggested for speed regulation with improved parameter robustness; a speed-current single-loop was proposed in 26 for electric vehicle applications; a linearized model-predictive control was presented in 27; and a data-driven model-predictive control was introduced in 28. None of these controls preserved the structural properties of the original dynamic system.

Few studies unifying model-predictive and passivity-based control can be found in the scientific literature. Most of them are based on theoretical properties rather than in the applications. 29 proposed a passivity-based model-predictive control inspired by the relationship between optimal control and model-predictive control. Moreover, passivity and dissipativity have been studied to achieve stability in economic models 30, but it is generally difficult to characterize dissipative systems in that context. A passivity-based model-predictive control was proposed in 31 for the regulation of a robot manipulator. The introduction of passive constraints proved to be particularly appealing, as robustness against model uncertainty was inherently ensured. Despite these advantages, the implementation of these controls was particularly challenging, as discussed in 32.

Contribution

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no previous application of passivity-based model-predictive control for speed regulation in PMSMs. This paper proposes an innovative approach that integrates port-Hamiltonian representation into the optimization problem. The contributions of this work include:

-

A novel control strategy based on passivity-based model-predictive control, which effectively regulates the speed of PMSMs.

-

A detailed analysis of the impact of different time horizons on the performance and execution times of the proposed control strategy.

-

An examination of how passivity and exponential stability constraints influence response times and simulation times according to the prediction horizon.

Outline

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the port-Hamiltonian model of the permanent magnet synchronous generator, as well as the conditions for the existence of the equilibrium point and the incremental model. The proposed model-predictive control is described in section 2, followed by the main stability properties in §3.2. Afterwards, section 4 presents a complete set of numerical experiments, finalizing with the conclusions and proposals for future work (§5).

Notation

Throughout this document, matrices are represented by capital letters, while vectors and scalars are denoted by low-case letters. The entries of the matrices are also represented by low-case letters. Thus, for a matrix

, there are

, there are

entries a

ij

; for any vector is the Euclidean norm and ∥x∥

Q

is

entries a

ij

; for any vector is the Euclidean norm and ∥x∥

Q

is

with

with

and the symbols ⪰ and ≻ represent the Loewner order of positive semi-definite matrices. The equilibrium point is represented by variables with an overline. The full nomenclature is presented below:

and the symbols ⪰ and ≻ represent the Loewner order of positive semi-definite matrices. The equilibrium point is represented by variables with an overline. The full nomenclature is presented below:

Nomenclature

ηNumber of pole pairs

µ m Inertia constant

ω e Angular speed

ψ m Flux in the permament magnents

τ m Electrical torque

τ m Mechanical torque

i d Input current in the direct axis

i q Input current in the quadrature axis

l d Equivalent inductance in the direct axis

l q Equivalent inductance in the quadrature axis

r s Stator resistance

v d Input voltage in the direct axis

v q Input voltage in the quadrature axis

Modeling the permanent-magnet synchronous machine

State-space representation

The model presented in 1 represents a PMSM connected to a constant mechanical load with a torque τ m :

This model is represented within a dq0 reference frame aligned with the q-axis1. The state variables are the currents in the stator (i d ,i q ) and the rotor’s electrical rotational speed ω e . The electrical torque is given by 2:

where κ = 2/(3η) and η is the number of pole pairs. The rest of the parameters correspond to the stator inductance l d ,l q , the stator resistance r s , the permanent magnet flux linkage ψ m , and the inertia µ m .

Port-Hamiltonian model

Port-Hamiltonian systems constitute a family of dynamic systems with useful structural properties such as passivity and disipativity. This family is a framework used to model and analyze physical systems by incorporating both energy-based methods and network theory. It is especially useful for representing complex interconnected systems with energy exchange, such as mechanical, electrical, hydraulic, or thermal systems. This type of dynamic systems is defined below.

Definition 1. A port-Hamiltonian system with dissipation is a dynamic system that can be described, in local coordinates, by the following input-state-output representation:

where x represents the state variables, u is the input, y is the output, J = −J ⊤ is an interconnection matrix, R = R ⊤⪰ 0 is a dissipation matrix, and H is a Hamiltonian function.

The permanent magnet synchronous generator admits a port-Hamiltonian model with state variables x 1 = l d i d , x 2 = l q i q , and x 3 = κµ m ω e as well as the control input u = (v d , v q , κτ m ). The input-output model is presented in 3, where the Hamiltonian function is a quadratic form given by 4:

The specific diagonal and positive semi-definite matrices Q = Q ⊤⪰ 0 and R = R ⊤⪰ 0 are defined as follows:

where R represents the natural damping of the dynamic system. In addition, a bilinear skew-symmetric interconnection matrix J(x) = −J(x)⊤ is defined, as given below.

where:

Finally, G and ∇H(x) are given by 6 and 7:

In this case, the existence and uniqueness of the solution can be ensured, since the nonlinearities of the model come in the form of the local Lipschitz continuous functions in

Conventionally, PMSMs are operated with a unitary power factor in order to reduce power losses2.Therefore, the equilibrium point is characterized by i

d

= 0. The desired rotational frequency is

, and

, and

Thus,

Thus,

The equilibrium of the port-Hamiltonian system is

Likewise, the input in the stationary state is obtained by isolating the variable u in (3), as shown below:

Likewise, the input in the stationary state is obtained by isolating the variable u in (3), as shown below:

Note that 8 is well defined since G is non-singular. Next, new state and input variables are defined:

and

and

These variables allow defining the following incremental model:

Part of the port-Hamiltonian structure is lost for this incremental model. In fact, the incremental model 9 can be represented by the following Lurie system3, where the nonlinear part is a port-Hamiltonian system:

where A is a 3 × 3 matrix that results from horizontally concatenating the column vectors associated with ∆x 1 and ∆x 2 and a zero vector, as given in (10):

It is worth noting that A = 0 for

, resulting in the original system 3. However,

, resulting in the original system 3. However,

for most practical applications. Hence, the incremental model is not port-Hamiltonian. This aspect has a direct consequence on the passive structure of the closed-loop system, which will be analyzed below.

for most practical applications. Hence, the incremental model is not port-Hamiltonian. This aspect has a direct consequence on the passive structure of the closed-loop system, which will be analyzed below.

Passivity

Several dynamic systems, such as port-Hamiltonian ones, share a common structural property named passivity, which reveals the energy behavior and easily allows to prove stability. The following definition is used in this article:

Definition 2. A dynamic system

with the state variables

with the state variables

, the inputs

, the inputs

, and the output

, and the output

is considered to be passive if there is a differentiable storage function

is considered to be passive if there is a differentiable storage function

with

with

, satisfying the differential dissipation inequality

, satisfying the differential dissipation inequality

across all solutions x(t) corresponding to the input function u.

As a port-Hamiltonian system, the model associated with the PMSM is a passive system with a storage function

, where

, where

arming

arming

(zero in this case). Unfortunately, the port-Hamiltonian structure is lost for the incremental model given by 9. Therefore, additional conditions are required to maintain passivity4.

(zero in this case). Unfortunately, the port-Hamiltonian structure is lost for the incremental model given by 9. Therefore, additional conditions are required to maintain passivity4.

Lemma 1. The incremental model given by9is passive with the storage function

. and the output

. and the output

if the following constraint is imposed:

if the following constraint is imposed:

where,

Proof. This can be easily proved by calculating S ˙ as given below:

Then, 9 is substituted, considering that J is skew symmetric, in order to obtain the following:

Now, 13 and 14 are used to obtain the following:

which satisfies 11 with the output y = G ⊤ Q∆x if inequality (12) holds.

Note that

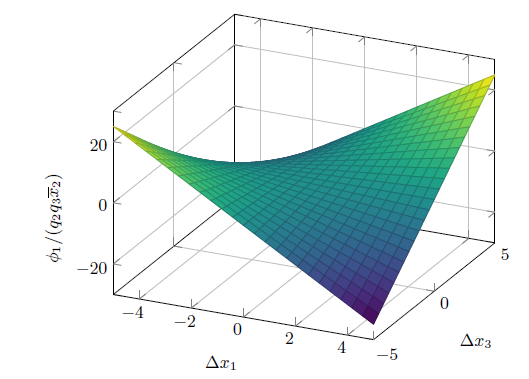

0 for any ∆x, given that R ⪰ 0. However, ϕ

1(∆x) may be a saddle; for example, for,

0 for any ∆x, given that R ⪰ 0. However, ϕ

1(∆x) may be a saddle; for example, for,

the following holds:

the following holds:

where q 1 = 1/l d ,q 2 = 1/l q and q 3 = 1/(κµ), as previously defined in 5. Eq. (12) holds in a stationary state since, in that case, ∆x = 0. The constraint is easily satisfied for small values of ∆x. However, it may be challenging for large deviations from the equilibrium point. Hence, 12 defines a feasible region for the optimization problem, as presented in the next section.

Fig. 1 shows ϕ 1 for a non-salient machine. There are regions in the state space where 12 is naturally satisfied, e.g., in the points where ϕ 1 ≤ 0. Other regions require imposing this passivity constraint, as proposed in the next section.

Figure 1: 3D representation of ϕ(∆x) for l

d

= l

q

(non-salient rotor)

Proposed model-predictive control

The optimal control problem

Model-predictive control can be considered as a variant of an optimal control problem applied in a receding horizon. The concept is based on four simple steps: measurement or estimate of the state x t (step 1) and the solution of the optimal control problem in a finite horizon T (step 2). This optimization problem yields a sequence of optimal inputs {u t ,u t+1 ,u t+2 ,...} over the entire horizon. However, we only execute the control command u t (step 3) and wait until the next step to take the measurements of the state x t+1 and solve the optimization model once again (step 4). These steps are schematically shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Schematic representation of the model-predictive control

In the case of the permanent magnet synchronous generator, the state space is assumed to be

, and the input space is defined by the set of feasible inputs. The external torque is known, making

, and the input space is defined by the set of feasible inputs. The external torque is known, making

This entails the following input set:

This entails the following input set:

The passivity condition given by Lemma 1 is incorporated into the optimization to ensure structural properties in closed-loop operation.

This work proposes the following optimal control problem, which is translated, without loss of generality, from t = 0 into t = T:

where M ≻ 0 is a weight matrix related to the inputs, and (z p ,z e ) are slack variables that allow defining soft constraints. Note that, the rest of the variables were already defined in the previous section.

Soft constraints are used to ensure the feasibility of the optimization problem, allowing for some degree of violation, which is penalized in the cost function through a quadratic form with weights α p and α e . Unlike hard constraints, which must be satisfied at all times, soft constraints provide the control optimization process with a certain degree of flexibility. However, it is expected that z p = z e = 0 for most of the control execution time. In this case, ϵ is a small positive constant used to ensure exponential stability, as presented in the next section.

Stability analysis

Proving stability in nonlinear controls is challenging. In particular, stability in model-predictive control is usually obtained by adequately selecting the terminal conditions 34. These conditions include a penalization factor or a constraint associated with the time t = T. In this case, a different approach was employed, wherein stability is imposed by the passivity conditions. Next, some of the basic concepts required for stability analysis are reviewed.

Theorem 1 (See (35) §3.1). Consider a nonlinear dynamic system =

and assume that there is a continuously differentiable function

and assume that there is a continuously differentiable function

V :

, such that

, such that

Then, the zero solution is stable in the sense of Lyapunov. If the last inequality is strictly satisfied, then the system is asymptotically stable. Finally, the system is exponentially stable if V satisfies

It is important to recall that exponential stability is a stronger result than asymptotic stability. Exponential stability implies that the deviations from the equilibrium state decay at an exponential rate. This means that the system returns to a stable equilibrium state more quickly in comparison with systems that only exhibit asymptotic stability. A faster decay is often crucial in practical applications, in order to ensure a swift recovery from perturbations. Moreover, exponential decay provides a predictable and well-defined rate at which the system returns to equilibrium. This rate can be used in practice for further stability analysis of the entire system.

In our case, the passivity condition imposed on the optimal control problem allows easily proving exponential stability, as presented below:

Theorem 2. Consider the incremental model9, where the input ∆u is calculated through the optimal control problem15. Suppose that the feasibility of the optimization problem is ensured in every state along the closed-loop trajectory with z p = z e = 0. Then, the resulting closed-loop system is exponentially stable.

Proof. First, the conditions for the passivity of the incremental model are established. Note that inequality 12 holds when z

p

= 0. In that case, the system is passive, so it holds that

. Moreover, when

. Moreover, when

, with

, with

and

and

. Finally, exponential stability is proved by invoking Theorem 1

. Finally, exponential stability is proved by invoking Theorem 1

Simulations and results

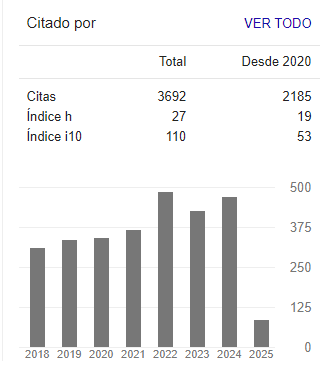

Numerical experiments were performed using Casadi in the Matlab-Simulink environment (36) in order to validate our proposal. All the parameters of the PMSM are presented in Table I

Table I: Parameters of the permanent magnet synchronous machine

Direct collocation with multiple shooting was employed to solve the optimal control problem. Discretization was carried out using an implicit Runge-Kutta method to ensure numerical stability. Three numerical simulations were performed, aiming to evaluate different features of the control, namely:

S1 : An analysis under different horizons was considered for the optimal control problem.

S2 : The effects of the passivity and the exponential stability constraint were evaluated.

S3 : The performance of the proposed control was compared against those of the passivity-based speed (PBS) control presented in 14.

The tuning parameters for the passivity-based model predictive control were Q = diag((1/l d ,1/l q ,1/(κµ))) and M = diag((1.,1,)) × 10−3.

Results of simulation S1

This subsection studies the effect of different step horizons on the proposed control strategy. Fig. 3 illustrates the dynamic responses of the stator currents Figs. 3a and 3b and the rotor’s electrical rotational speed (Fig. 3c) for the proposed control applied to the PMSM under different horizons. The reference of the electrical rotational speed x¯3 varies by ±ω e . Fig. 3d presents the simulation times for each of the prediction horizons analyzed.

Figure 3: Transient behavior of the proposed control applied to the PMSM under different horizons

By analyzing Fig. 3, it can be noted that, for the various prediction horizons employed, the motor achieves the desired references in less than 30 ms (Fig. 3c). Additionally, after five prediction horizons, the dynamic responses of the permanent magnet synchronous motor exhibit a similar behavior. Meanwhile, for a one-step horizon, the response time takes 10 ms longer on average to stabilize, albeit with the shortest simulation time, reporting reductions of 42.74 and 88.71 % when compared to the seven- and 19-step horizons (Fig. 3d). This indicates that, in a larger system, a longer horizon will be the best option.

Results of simulation S 2

This section analyzes the effect of including (or not) the passivity or the exponential stability constraint for the step horizons h = 1 and h = 19. The first constraint analyzed is passivity, whose effect is determined by whether it is eliminated from the optimization model presented in (15). Fig. 4 shows the dynamic responses of the stator currents (Figs. 4a and 4b) and the rotor’s electrical rotational speed (Fig. 4c) for the proposed control applied to the PMSM under various horizons. The reference of the electrical rotational speed x¯3 remained between ±ω e . Fig. 4d depicts the simulation time under the prediction horizons h = 1 and h = 19 with and without the passivity constraint.

Figure 4: Effect of applying (solid line) or not applying (dashed line) the passivity constraint

In Fig. 4, note that, when the prediction horizon is equal to one (h = 1), the impact of the passivity constraint on the proposed control’s performance becomes evident, as the simulation times increase Figs. 4a and 4c . When the prediction horizon is set to h = 19, the passivity constraint has minimal impact on the performance of the proposed control. This suggests that, for extended prediction horizons, the proposed control exhibits a passive behavior. Fig. 4d shows that the simulation times increase by about 3.08 and 3.80 times with the inclusion of the passivity constraint in the optimization model for h = 1 and h = 19, respectively.

Next, the effect of the exponential stability constraint on the optimization model 15 will be analyzed. Fig. 5 presents the dynamic responses of the proposed model with and without the constraint. Figs. 5a and 5b illustrate the stator currents i d and i q , respectively. Fig. 5c shows the rotor’s electrical rotational speed, and Fig. 5d depicts the simulation times for the prediction horizons h = 1 and h = 19 with and without the constraint.

Figure 5: Effect of applying (solid line) or not applying (dashed line) the exponential stability constraint

By analyzing Fig. 5, it can be concluded that the effect of the exponential stability constraint on the proposed control is an increase in simulation times. This effect becomes more pronounced as the prediction horizon increases (Figs. 5b and 5c). Fig. 5d shows that including the constraint increases the simulation time by factors of 2.57 and 2.69 for h = 1 and h = 19, respectively.

4.3. Results of simulation S3

This subsection compares the performance of the proposed control against that of the PBS control described in 14. Fig. 6 depicts the dynamic responses of the stator currents (Figs. 6a and 6b) and the rotor’s electrical rotational speed (Fig. 3c) for the proposed control and the PBS approach applied to the PMSM. Our proposal was analyzed with the step horizons h = 1 and h = 19.

Figure 6: Results of the comparison between the proposed control with h = 1 and h = 19 and the PBS control

Note that, with h = 1, our proposal exhibited a similar performance to that of the PBS control in regulating the motor’s speed. However, when the step horizon was increased to h = 19, the proposed control reported a faster response time and a quicker settling, indicating a superior performance.

Conclusions

This paper presented a valuable contribution to the field of control for permanent magnet synchronous machines. The proposed approach, based on passivity modeling and model-predictive control, represents an innovative and effective method for speed regulation in PMSMs. The results demonstrate that our strategy achieves the desired references in less than 30 ms under various prediction horizons. Furthermore, after five prediction horizons, the dynamic responses of the permanent magnet synchronous motor maintain a similar behavior. However, with a prediction horizon of h = 1, the response time takes 10 ms longer on average to stabilize when compared to the other horizons considered. Still, the simulation time for the one-step horizon is the shortest, showing reductions of 42.74 and 88.71 % compared to h = 7 and h = 19, respectively. This demonstrates that a longer prediction horizon can be more effective in larger systems.

We analyzed the impact of including or excluding the passivity and exponential stability constraints on the proposed control. The results indicated that, for the prediction horizon of one step, the passivity constraint significantly affects the response time of our proposal, slowing down its performance. Conversely, for h = 19, the passivity constraint has minimal impact, suggesting that, for longer prediction horizons, the proposed control exhibits a passive behavior. Additionally, including this constraint leads to increased simulation times, i.e., approximately 3.08 and 3.80 times longer for h = 1 and h = 19, respectively.

On the other hand, the exponential stability constraint decelerated the proposed control, with this effect becoming more noticeable as the prediction horizon grew longer. The inclusion of this constraint increased the simulation times by a factor of 2.57 and 2.69 for h = 1 and h = 19, respectively.

These findings contribute to the understanding of the factors influencing control performance and provide guidance for the practical implementation of efficient PMSM control systems. In summary, this study underscores the importance of integrating passivity and exponential stability constraints in the advancement of sophisticated control strategies for industrial applications. Finally, a comparison between our proposal and PBS control was conducted, with the former demonstrating a superior performance.

As a future endeavor, the controller could be expanded to various applications, including the regulation of synchronous machines in power systems and voltage source converters. Expanding the controller’s scope to these domains would further validate its effectiveness and broaden its practical applicability in various industrial contexts

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgments

This work is a partial result of research project no. 6-24-2, funded by the Research, Innovation, and Extension Vice-Principalship of Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira.

References

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2024 Alejandro Garcés-Ruiz, Walter Julián Gil González

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0.

A partir de la edición del V23N3 del año 2018 hacia adelante, se cambia la Licencia Creative Commons “Atribución—No Comercial – Sin Obra Derivada” a la siguiente:

Atribución - No Comercial – Compartir igual: esta licencia permite a otros distribuir, remezclar, retocar, y crear a partir de tu obra de modo no comercial, siempre y cuando te den crédito y licencien sus nuevas creaciones bajo las mismas condiciones.

2.jpg)