DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/23448393.21898Published:

2025-04-21Issue:

Vol. 30 No. 1 (2025): January-AprilSection:

Mechanical EngineeringDesign and Implementation of a Virtual Laboratory for the Analysis and Synthesis of Mechanisms

Diseño e implementación de un laboratorio virtual para el análisis y síntesis de mecanismos

Keywords:

Virtual Laboratory, kinematics, dynamics, synthesis, mechanism (en).Keywords:

Laboratorio virtual, cinemática, dinámica, síntesis, mecanismos (es).Downloads

References

W. Ali, “Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: A necessity in light of COVID-19 Pandemic,” Higher Ed. Stud., vol. 10, no. 3, art. 16, 2020. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v10n3p16

United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, Report of the Expert Meeting on Virtual Laboratories. Paris, France: UNESCO, 2000.

C. Infante, “Propuesta pedagógica para el uso de laboratorios virtuales como actividad complementaria en las asignaturas teórico-prácticas,” Rev. Mex. Inv. Ed., vol. 19, no. 62, pp. 917-937, 2014. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=14031461013

A. Lorandi ,G. Hermida, J. Hernández, and E. Ladrón de Guevara, “Los laboratorios virtuales y laboratorios remotos en la enseñanza de la ingeniería,” Rev. Int. Ed. Ing., vol. 4, pp. 24-30, 2011.

J. Cabrera Medina and I. Sánchez Medina, “Laboratorios virtuales de física mediante el uso de herramientas disponibles en la Web,” Mem. Cong. UTP, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 49-55, 2016. https://revistas.utp.ac.pa/index.php/memoutp/article/view/1296

R. Radhamani et al., “What virtual laboratory usage tells us about laboratory skill education pre- and post-COVID-19: Focus on usage, behavior, intention and adoption,” Educ. Inf. Technol., vol. 26, pp. 7477-7495, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10583-3

L. Mishra, T. Gupta and A. Shree, “Online teaching-learning in higher education during lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic,” Int. J. Ed. Res. Open, vol. 1, art. 100012, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100012

F.D. Syahfitri et al., “The development of problem based virtual laboratory media to improve science process skills of students in biology,” Int. J. Res. Rev., vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 64-74, 2020. https://doi.org/10.20961/ijpte.v2i0.24952

N. Kapilan, P. Vidhya, and X.Z. Gao, “Virtual laboratory: A boon to the mechanical engineering education during COVID-19 pandemic,” High. Ed. Fut., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 31-46, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/2347631120970757

K. Achuthan, P. Nedungadi, V. Kolil, S. Diwakar, and R. Raman, “Innovation adoption and diffusion of virtual laboratories,” Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng., vol. 16, no. 9, pp. 4-25, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijoe.v16i09.11685

G. Singh, A. Mantri, O. Sharma, and R.,Kaur, “Virtual reality learning environment for enhancing electronics engineering laboratory experience,” Comp. App. Eng. Ed., vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 229-243 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.22333

N. Tuli, G. Singh, A. Mantri, and S. Sharma, “Augmented reality learning environment to aid engineering students in performing practical laboratory experiments in electronics engineering”, Smart Learn. Environ., vol. 9, art. 26, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-022-00207-9

C.Hao, A. Zheng, Y.Wang, and B.Jiang, “Experiment information system based on an online virtual laboratory,” Future Internet, vol. 13, no. 2, art. 27, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi13020027

F. Vahdatikhaki, I. Friso-van Den Bos, S. Mowlaei, and B. Kolloffel, “Application of gamified virtual laboratories as a preparation tool for civil engineering students,” Eur. J. Eng. Ed., vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 164-191, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2023.2265306

Y. Xiaoju et al., "Teaching practice of wind turbine practical training based on virtual teaching platform,” Comp. App. Eng. Ed., vol. 32, no. 2, art. e22710, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.22710

A. Sánchez-López, J. Jáuregui_Jáuregui, N. García-Carrera, and Y. Perfecto-Avalos, “Evaluating effectiveness of immersive virtual reality in promoting students’ learning and engagement: A case study of analytical biotechnology engineering course,” Front. Ed., vol. 9, art. 1287615, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1287615

V. Kolil and K. Achuthan, “Virtual labs in chemistry education: A novel approach for increasing student’s laboratory educational consciousness and skills”, Ed. Info. Technol., vol. 29, pp. 25307-25331, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-12858-x

S. Dong, F. Yu, and K. Wang, “A virtual simulation experiment platform of subway emergency ventilation system and study on its teaching effect”, Sci. Rep., vol. 12, art. 10787, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41598-022-14968-3

J. L. Calderón, “Aplicación de GeoGebra en la enseñanza de la cinemática de un mecanismo de cuatro barras,” Rev. Inst. GeoGebra São Paulo, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 3-19, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.23925/2237-9657.2020.v9i2p003-019

B. Stahre Wästberg et al., "Design considerations for virtual laboratories: A comparative study of two virtual laboratories for learning about gas solubility and colour appearance,” Ed. Info. Technol., vol. 24, pp. 2059-2080, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-09857-0

V. M. Gándara, “Usos educativos de la computadora,” in El proceso de desarrollo y el diseño de interfaz al usuario, J. M. Álvarez and A. M. Bañuelos, Eds., Ciudad de México, Mexico: UNAM, 1994.

A. Joshi, M. Vinay, and P. Bhaskar, “Impact of coronavirus pandemic on the Indian education sector: perspectives of teachers on online teaching and assessments,” Inter. Technol. Smart Ed., vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 205-226, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITSE-06-2020-0087

A. Cova, X. Arrieta, and V. Riveros, “Análisis y comparación de diversos modelos de evaluación de software educativo,” Rev. Ven. Info. Tecnol. Conoc., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 45-67, 2008.

O. González, M. A. Aguilar, F. J. Aguilar, and M. L. Matheu, “Evaluación de entornos inmersivos 3D como herramienta de aprendizaje B-Learning,” Ed. XX1, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 417-440, 2018. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.16204

Y. Arguelles, “Metodología para la evaluación de laboratorios virtuales en entornos 3D,” M.S. thesis, Universidad de Moa, Cuba, 2021.

J. Li and W. Liang, “Effectiveness of virtual laboratory in engineering education: A meta-analysis,” PLoS ONE, vol. 19, no. 12, art. e0316269, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0316269

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 19 de febrero de 2024; Revisión recibida: 16 de marzo de 2025; Aceptado: 16 de abril de 2025

Abstract

Context:

This paper presents the design and implementation of a virtual laboratory developed as a pedagogical support tool for courses in mechanisms analysis and synthesis within Mechanical Engineering programs.

Method:

Our virtual laboratory was developed using GeoGebra, Moodle, and Matlab. The design methodology was structured into four key stages: requirements analysis, conceptual design, content development, and implementation and evaluation.

Results:

The outcome is a comprehensive virtual laboratory framework comprising 12 interactive exercises focused on the analysis and synthesis of planar mechanisms. This paper outlines the functional features of the virtual laboratory, including its graphical user interface, user guide, instructional practices, and assessment procedures - demonstrating its value as an effective tool to support and enhance both teaching and student learning.

Conclusions:

The virtual laboratory allowed students to conceptualize through the visualization of kinematic and dynamic variables, offering a complementary and interactive alternative to traditional theoretical instructions. This aligns with active learning strategies, as the teacher reported greater student engagement. Students advanced at their own pace through the exercises and were able to observe how geometric and functional modifications in mechanisms influence their kinematic and dynamic behavior.

Keywords:

virtual laboratory, kinematics, dynamics, synthesis, mechanism.Resumen

Contexto:

Este trabajo presenta el diseño y la implementación de un laboratorio virtual desarrollado como soporte pedagógico en la enseñanza de la teoría de máquinas y mecanismos en ingeniería mecánica.

Método:

Nuestro laboratorio virtual fue desarrollado utilizando Geogebra, Moodle y Matlab. La metodología de diseño se estructuró en cuatro etapas clave: análisis de requerimientos, diseño conceptual, desarrollo de contenido e implementación y evaluación.

Resultados:

El resultado es un marco integral de laboratorio virtual que contiene 12 ejercicios centrados en el análisis y la síntesis de mecanismos planos. Este artículo presenta las características funcionales del laboratorio virtual, incluyendo su interfaz gráfica de usuario, guía de usuario, prácticas institucionales y procedimientos de evaluación -demostrando su valor como herramienta efectiva para apoyar y mejorar la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de los estudiantes.

Conclusiones:

El laboratorio virtual permitió a los estudiantes conceptualizar mediante la visualización de variables cinemáticas y dinámicas, ofreciendo una alternativa complementaria e interactiva a la instrucción teórica tradicional. Esto se alinea con las estrategias de aprendizaje activo, pues el docente reportó un mayor compromiso por parte de los estudiantes. Los estudiantes avanzaron a su propio ritmo a través de los ejercicios y pudieron observar cómo las modificaciones geométricas y funcionales en los mecanismos influyen en su comportamiento cinemático y dinámico.

Palabras clave:

laboratorio virtual, cinemática, dinámica, síntesis, mecanismos.1. Introduction

In the teaching-learning of the analysis and synthesis of mechanisms, graphic and analytical methodologies are regularly used. These approaches are complementary: the graphical methodology provides a visual representation of velocity, acceleration, and force vectors, allowing students to better understand the physics of motion; while the analytical methodology relies on mathematical models, laying the foundation for simulation and optimization processes. Additionally, it enables the parameterization, systematization, and solution of multiple configurations of the mechanisms under study.

The creation and implementation of virtual laboratories are widespread trends in engineering education. These trends aim to establish flexible university curricula and promote diverse student-centered teaching-learning methodologies, thereby fostering autonomous learning. The application of new teaching methodologies has reshaped classrooms, workspaces, scheduling, and student engagement in their educational journey. This transformation has been particularly evident in recent years, accelerating the shift from traditionl face-to-face instruction to virtual formats. Consequently, technology has emerged as a fundamental mediator in the evolving teaching landscape 1.

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) and learning and knowledge technologies (LKTs) have expanded the scope of learning and participation, enabling the exposition, manipulation, analysis, synthesis, application, and evaluation of ideas. These activities are enhanced through direct observation and reflective engagement in virtual environments. In this context, virtual laboratories play a pivotal role, providing students with immersive, interactive, and adaptable learning experiences that bridge the gap between theoretical concepts and practical applications.

Virtual laboratories (VLs) serve as an electronic workspace designed for remote collaboration and experimentation in research and other creative pursuits 2. They facilitate the production and dissemination of academic results by leveraging state-of-the-art information and communication techniques. Particularly, during the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, VLs proved to be powerful educational technological tools 3.

Some of their main advantages include:

- Interactivity, enabling learners to manipulate and transform instructional material, data, and information

- Accessibility

- Methodological variability

- Flexibility in terms of time and space

- Active student participation

- Encouragement of self-learning

VLs are computational systems that can be accessed via the Internet. They are based on theoretical models, simulate processes, and provide dynamic object visualization in a way similar to conventional laboratories 4. These systems can be implemented as standalone units containing multiple virtual experiments on the same platform, or as integrations of experiments from different platforms. Tools such as GeoGebra, Matlab Live, MatlabApps, Java, Flash, CGIs, PHP, and Wolfram facilitate the development of online applications, thus contributing to the creation of VLs.

Various open-access interactive simulation sources, including Walter-Fendt (https://www.walter-fendt.de/html5/phes), Educaplus (http://educaplus.org), and PhET (https://phet.colorado.edu), offer numerous science and mathematics applets. Some of these applets can be easily embedded in platforms like Moodle, which is widely used in university settings. Prior to the pandemic, the use of simulations in VLs for physics teaching in engineering courses had already demonstrated benefits in fostering autonomous learning 5. This trend continued during and after the pandemic, leading to increased pedagogical research on the perception of VLs in traditional education 6-9. The growing interest in VLs suggests their potential adoption by higher education institutions and even their incorporation into state policies, as exemplified by India's implementation under the theory of diffusion of innovation 10. Research findings indicate that the acceptance, intention to use, and perceived relevance of this technology significantly influence user perception.

Over the past three years, numerous implementations of VLs across various fields of engineering have been reported. In 11-13, VLs have been applied to circuit-related experiments in electronics engineering. In civil engineering, 14 explores the effectiveness of a virtual laboratory designed to prepare students for concrete laboratory sessions, allowing them to become familiar with experimental procedures beforehand. The study reported a 16 % reduction in time spent in the physical lab.

In mechanical engineering, 15 addresses the development and implementation of a virtual simulation platform for teaching wind turbine assembly practices. Given the large size and high cost of turbine components, this platform offers a valuable alternative for practical training, which is often limited in traditional lab settings.

In the field of biotechnology, 16 evaluates the impact of an immersive virtual reality (IVR) intervention on student learning and academic engagement, particularly in the instruction of infrared (IR) spectroscopy. This study found that students who participated in an IVR experience scored higher on IR-related exam questions compared to control groups and reported greater academic engagement as well as a positive attitude towards the use of IVR in learning.

In chemical engineering, 17 explores the integration of VLs into chemistry education to enhance students' understanding and practical skills. The results indicated that VLs were effective in reducing common misconceptions among students.

Finally, in safety engineering, 18 describes the development and implementation of a virtual simulation platform for teaching emergency ventilation systems in subway environments - a type of experiment that cannot be conducted in real-world conditions due to its hazardous nature.

In the field of mechanisms analysis and synthesis, applications have predominantly been developed using GeoGebra, a software that parameterizes geometric figures based on relationships between and the properties of entities (e.g., the links of a mechanism and velocity and acceleration vectors). This enables the creation of interactive applets. Collections of individual applets, such as the one presented by 19, provide substantial support for teaching courses. However, their use has been historically limited to kinematic analysis, without incorporating dynamic analysis, which is crucial in the design process.

Since machine design and construction involve topological design, kinematic and dynamic analysis, simulation, and mechanisms optimization, this work primarily aims to implement numerical methodologies for computational, graphical, and analytical solutions. This objective is fulfilled through the development of a VL dedicated to teaching the dimensional synthesis of mechanisms, as well as their kinematic and dynamic analysis.

The following sections describe the design methodology of the VL for mechanisms analysis and synthesis, detailing the requirements analysis, conceptual design, content development, implementation, and evaluation stages. Subsequently, initial evaluation comments and feedback gathered from user surveys regarding performance, content, learning value, presentation, challenges, and recommendations are discussed. The VL was implemented within the Mechanical Engineering program at the Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira as part of its educational innovation efforts. Finally, this paper concludes by presenting key findings relevant to the authors.

2. Methodology

The design of VLs, conceived as interactive digital objects within the academic environment, requires a structure that considers not only general and specific objectives and content, but also aesthetic and functional attributes. According to 20, designing a VL requires a clear understanding of its purposes and context. The appropriate technology must be selected to ensure efficient media design and use. The level of realism should align with the intended purpose and target users, and learning guides should be provided both before and after the VL session.

21 further emphasizes that, in order for a digital object to be effective, its design must account for user type, task analysis, content structure, content presentation, and navigation modes - both within the object itself and across the network.

Building upon these foundational principles, a structured methodology for the design and implementation of a VL was established. This process generally includes the following stages: requirements analysis, conceptual design, practice content development, implementation, and evaluation.

2.1. Requirements analysis

This stage defines the general characteristics that the VL should possess, including the number and scope of practices, the format of the graphical interface, interactivity adapted to the subject, applications, and potential users. Additionally, it encompasses the documentation and information required for the access, use, and further development of the laboratory.

The designed laboratory is intended for students enrolled in the courses titled Theory of Machines and Mechanisms, and Synthesis of Mechanisms. It consists of practices developed as individual learning objects within the same environment. These objects are later integrated into a unified website hosted on the institution's Moodle platform.

Given the subject matter and the learning objectives of the practices, the requirements for each learning object are as follows:

- Graphic interface: Includes dialog boxes and control bars for adjusting input parameters, enabling the real time visualization of changes in the polygons that represent the kinematic and dynamic variables of the mechanism. This interface also allows for simulations of the analyzed mechanisms.

- Interactivity: Allows users to navigate between the different types of analysis (kinematic, dynamic, and simulation) through tabs. Users can modify the lengths and positions of links and frames. For dimensional synthesis, interactivity facilitates the exploration of design parameters (precision points), synthesis type (guided, trajectory or function), and visualization of rotation criteria, transmission angles, and the simulation of the synthesized mechanism.

- Documentation and help resources: Provides guidance for each practice.

2.2. Conceptual design of the laboratory

During the conceptual design stage, the platform, structure, and layout of the VL are defined. Considerations regarding the selection of suitable software for practice development and implementation are also addressed.

The laboratory's operating platform (the LMS Moodle V3.11 package) was selected based on the institution's existing virtual infrastructure. This learning management system (LMS) enables the planning and implementation of modules for academic courses, as well as diverse evaluation strategies that facilitate student progress tracking 22.

The structure of the virtual laboratory is specifically designed for subjects related to the theory of mechanisms. It was conceptualized as a combination of codes using both open- source and licensed software - some for the graphical development of mechanisms analysis and synthesis (e.g., the creation of velocity, acceleration, and force polygons; graphical dimensional synthesis), and others for analytical processing using mathematical expressions with numerical resolution.

The conceptual design includes the creation and hosting of interactive applications executable via a web browser, eliminating the need for additional software installation. The diagramming process of the practices considers the learning levels, sequence, interrelation, and complexity of the exercises. This structured approach ensures that the course begins with simple exercises and progressively introduces more complex mechanical systems along with advanced programming, visualization, and simulation tools.

2.3. Design and content

During the design and content development stage, solution algorithms are programmed in line with the laboratory's objectives, intended applications, and user base. These algorithms are tailored to the specific requirements of each practice, while help and information materials are seamlessly integrated. Additionally, interactivity and navigability are carefully structured to ensure a comprehensive user experience.

Table I presents the available practice selections, categorized by study type: mechanism analysis, and mechanism synthesis. The choice of specific mechanisms was based on their relevance to the design of machines. Many industrial machines are derived from modifications of the four-bar, crank-rocker, and crank-slider mechanisms or their combinations. These mechanisms are fundamental in various applications, including positive displacement pumps, compressors, internal combustion engines, presses, die-cutting machines, lifting platforms, and rectilinear motion systems. Practices focused on mechanism synthesis are closely aligned with the course content and were defined according to this criterion.

Table I: Practices in the proposed virtual laboratory

Type of study

Practice

Kinematic and dynamic mechanism analysis

Four-bar linkage mechanism, slider crank mechanism, scotch yoke mechanism(collisa mechanisms), Whitworth quick return mechanism, cam mechanism, gear mechanism

Dimensional synthesis

Three-precision-point kinematic synthesis (guidance, established supports, and trajectory), four-precision-point kinematic synthesis, four-bar function generator, slider-crank function generator, cognate mechanisms, synthesis of cam mechanisms

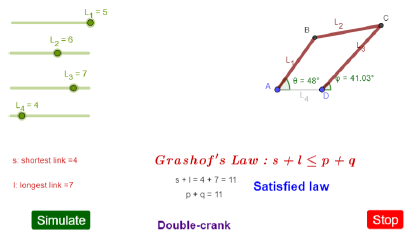

The practices within the graphical environment were developed using Geogebra and integrated as applets into their corresponding section. One such example is the practice involving a four-bar linkage mechanism, which is depicted in Fig. 1. In this section, students can validate the mechanism's rotation criteria through an interactive application, where they can manipulate the link lengths and verify compliance with Grashof's law. Additionally, students are prompted to simulate the motion of the mechanism by rotating the input link according to the given configuration. The documentation for this section covers the concept of rotatability and its associated criteria. Moreover, students are encouraged to modify the link dimensions with predefined values, allowing them to observe of various kinematic inversions achieved.

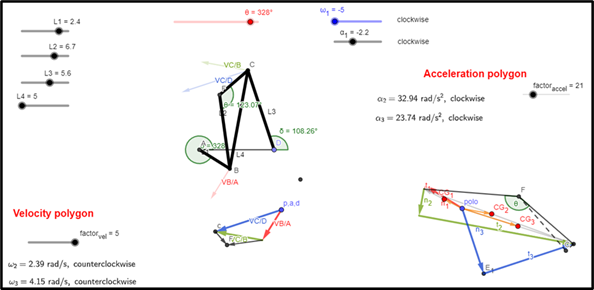

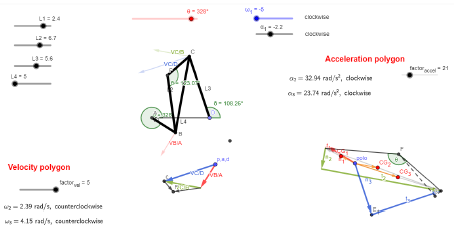

For all kinematic analyses, interactive applets allow users to modify the dimensions of the mechanisms. Users can adjust the magnitudes and directions of the velocities and angular accelerations of the input links using sliders (Fig. 2), which allows them to observe the resulting kinematic changes.

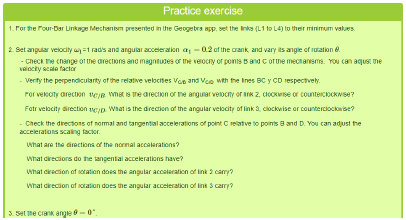

In the previous stage, the accompanying documentation explains the construction of velocity and acceleration polygons. Through guided practice exercises, students are encouraged to introduce kinematic changes and observe how the shapes and dimensions of these polygons are transformed. Directions, suggestions, and questions - such as those exemplified in Fig. 3 - are incorporated to enhance students' understanding and internalization of the material.

Figure 1: Graphical user interface of the Grashof module for the four-bar linkage mechanism

Figure 2: Graphical user interface for the kinematic analysis of a four-bar linkage mechanism

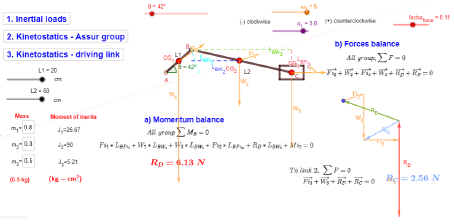

In the sections related to graphical kinetostatics, the process begins with the calculation of inertial loads added to the mechanism, allowing students to track how these loads change as the geometric parameters are varied. Subsequently, the forces within the kinematic pairs are calculated for each Assur group. Finally, the compensatory moment in the primary or input link of the mechanism is determined. Fig. 4 displays the kinetostatic calculation module for the slider-crank mechanism. As previously mentioned, adjustments can be made to both the mechanisms' dimensions and the kinematic variables of the input element (e.g., angular velocity and acceleration).

Figure 3: Follow-up practice guidelines related to kinematic analysis of a four-bar linkage

Figure 4: Graphical user interface for the kinetostatics of the slider crank mechanism

Parameterizing constraint forces using these graphical methods is complex and requires numerous auxiliary variables to determine the magnitudes, directions, and signs of the forces and moments analyzed in each section. The parametric graphical method implemented in this VL allows users to instantly visualize the points where the maximum forces occur. This real-time visualization facilitates the analysis of variations in kinematic or dynamic parameters.

The developed VL also addresses the kinematics of gear trains. Within the gear practice modules, students determine transmission ratios and analyze speed variations across different types of gear trains: simple, compound, and epicyclic. Fig. 5 illustrates two of the implemented modules.

Figure 5: Graphical user interface of the module for compound and epicyclic gear trains

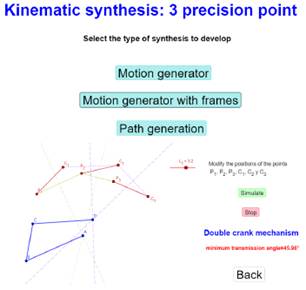

Regarding graphical dimensional synthesis, the exercises are designed to let students select the type of synthesis they wish to perform and modify pre-defined design points. Construction lines are displayed to guide them in following the explanations provided in the documentation, facilitating a step-by-step approach to the requested synthesis, as presented in Fig. 6.

A crucial parameter in dimensional synthesis is the minimum achievable transmission angle of the synthesized mechanism, which serves as an indicator of mechanical advantage. In graphical synthesis, this value can be determined upon completion of the design process. This application enables students to quickly generate alternative mechanisms by adjusting points of interest, modifying mechanism frames, or altering assumed link lengths. Such adjustments help to optimize motion transmission while considering factors like Grashof's law compliance and transmission angle minimization.

Figure 6: Graphical user interface of the dimensional synthesis module (using 3 precision points)

In the context of analytical methodologies, software selection should consider the students' level of training within the courses in Theory of Machines and Mechanisms, and Mechanisms Synthesis. Since students have not yet completed their coursework in programming and numerical methods, Matlab -which is available online on our institution's platform - is preferred. Matlab offers built-in functions for solving nonlinear equation systems (solve, fsolve), which are essential in position analysis. Additionally, the availability of Matlab Online ensures that students can access the software from any location at any time, significantly enhancing the VL's role as a self-training and self-learning tool.

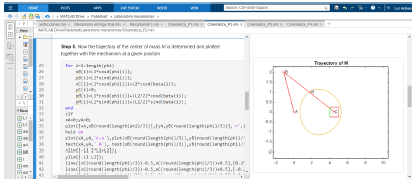

For analytical methodology practices, interactive executable documents (Matlab Live) have been developed. These documents integrate program code, images, and explanatory texts to simplify the understanding of the implemented algorithms. Fig. 7 presents one of the executable documents developed within the VL.

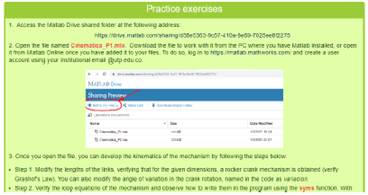

To facilitate access to Matlab-based practices, dedicated sections with access instructions have been provided on the Moodle platform. These sections allow students to download the necessary files and store them in their personal Matlab Drive folder. Students can work on these files remotely using Matlab Online. Fig. 8 presents the access instructions for one of the practice exercises.

Figure 7: Executable document for the kinematic analysis of a slider-crank mechanism

Figure 8: Follow-up practice guidelines for accessing analytical practices

Each practice includes documentation detailing the formulation of analytical expressions required for kinematic and kinetostatic analyses. For instance, Fig. 9 presents selected sections of the development of a four-bar linkage mechanism.

2.4. Implementation

The virtual laboratory has been implemented on the Moodle platform, utilizing tabs in order to allow students to seamlessly navigate through various practice exercises. Each tab contains sections with detailed descriptions of the mechanism and the corresponding analyses - both kinematic and kinetostatic - as illustrated in Fig. 10. Within each section, students can access supporting documentation, interactive applets (created using GeoGebra), and executable documents (created in Matlab) to facilitate practice.

Figure 9: Documentation for the kinematic analysis of a practice within the VL

Figure 10: Implementation of the VL on the Moodle platform

2.5. Evaluation

The assessment of a digital educational resource's value to users is essential to determine its impact on the learning process, along with other factors that define its quality. Evaluation becomes particularly relevant once the digital resource is in use. Various educational software evaluation models can be found in the literature, with notable contributions made by 23, 24, and 25. In general, these evaluations aim to measure both the technical and educational quality of the material. Table II presents a summary of the criteria incorporated into the evaluation instrument.

The purpose and objectives are clearly stated. Instructions are clear and easily understandable. System requirements. Adequate technical specifications are provided. Ease of use. The software is user-friendly and intuitive. Information accuracy. The content is accurate and reliable. Appropriate difficulty level. The software aligns with the intended level of difficulty. Provides flexible timing options for practice. Generates interest and engagement among users. Offers clear and comprehensible instructions. Includes realistic and relevant examples for practice.

Table II: Features for evaluating educational software

Category

Dimension

Features

General information

Documentation

Technical and pedagogic aspects

Specific information

Software for practice

The main page of the VL features a section for user feedback and general recommendations, as well as a digital form that students and other users can complete. Table III presents a selection of the questions included in this form.

Table III: Sample questions from the VL digital evaluation form

Question

Rating

Are the objectives of the VL clearly documented?

1-5

Is the planning process evident in the lab's development, including its

1-5

sequence and use of computational resources?

Is the content of the VL aligned with the course objectives?

1-5

Does the sequence of practice exercises facilitate an appropriate study of the topics?

1-5

Is the practical material useful for the course?

1-5

How would you rate the presentation and organization?

1-5

Is there a clear connection between practical and theoretical content?

1-5

Was the allocated time sufficient to complete the exercises in their entirety?

1-5

Did you face difficulties in completing the exercises due to a lack of previous knowledge in the studied subjects?

1-5

How easy was it to access the exercises?

1-5

Were the computer programs used in the practice exercises appropriate?

1-5

Please mention some positive aspects of the VL:

Open answer

Please mention some negative aspects of the VL:

Open answer

Do you have any recommendations for improving the VL?

Open answer

3. Results and discussion

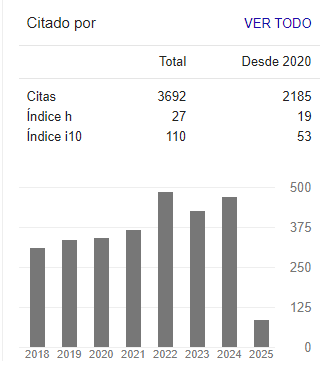

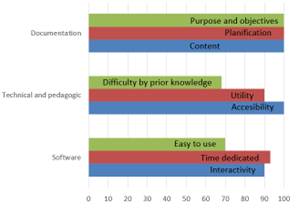

This evaluation facilitated the identification of the key challenges and benefits associated with the VL. Fig. 11 presents some of the categorized observations. Notably, users assign high ratings to the documentation provided in the laboratory. Additionally, the ease of access and the perceived value of the contents in student's academic training are evident.

Figure 11: Some evaluative aspects of the VL

The findings are consistent regarding several aspects with those reported in a comprehensive study on the effectiveness of VLs in engineering education 26. This study aggregated data from 46 individual investigations extracted from 22 publications. Various educational outcomes were evaluated using the Hedges g, a widely accepted effect size metric employed in meta-analysis and statistical research to quantify the standardized difference between two groups, such as experimental and control groups.

According to conventional interpretation, a Hedges g value of approximately 0.2 indicates a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and values greater than 0.8 a large effect.

One of the most notable results of the study is the strong positive impact of VLs on student motivation and engagement (Hedges g=3.571), a perception that was also reflected in the evaluation of the VL developed in our work. The reported usefulness and the favorable feedback provided by students support the conclusion that VLs foster greater student involvement in the learning process.

In contrast, a more modest effect on academic performance and skill acquisition was reported, with effect sizes ranging between 0.6 and 0.7, as noted in 26. This trend was also observed in the feedback from students participating in the VL on mechanisms: a considerable number of individuals indicated difficulties stemming from insufficient prior knowledge, particularly regarding computational tools for solving equations and the analytical modeling of mechanical systems.

Additionally, 26 identified a negative cognitive load effect in certain scenarios (Hedges g=-2.107), suggesting that students may struggle with information overload. A comparable issue was observed in our implementation, which was primarily related to the extensive time investment required and the lack of prior training in the software tools used in the practical exercises.

Nevertheless, in terms of content presentation and instructional design, students expressed positive attitudes towards the interactivity and flexibility offered by the virtual environment.

4. Conclusions

This paper presented a virtual laboratory designed to enhance learning in courses on the analysis and synthesis of mechanisms within undergraduate mechanical engineering programs. The development methodology integrated Geogebra, Moodle, and MatLab platforms, covering the entire process from conceptual design to implementation. The design adhered to the learning objectives of the Theory of Mechanisms and Machines and Mechanisms Synthesis courses, emphasizing content organization, user interactivity, autonomous learning, and learning outcomes assessment.

As a new initiative at our institution, the VL currently includes 12 practical exercises focused on the analysis and synthesis of planar mechanisms. The digital platform allows for future expansion by users and provides a framework for developers to apply user feedback for iterative improvement.

The effectiveness of the VL as a pedagogical tool to support and enhance both teaching and learning has been evaluated during its initial deployment in courses on mechanisms. Our VL empowers students to better understand concepts by visualizing kinematic and dynamic variables in various types of mechanisms. It serves as an alternative and complementary tool to traditional lectures, supporting active learning methodologies that foster student engagement. Students can progress at their own pace, observing how geometric and functional changes affect the kinematic and dynamic behavior of mechanisms. User feedback highlights the benefits of repeating exercises as needed, as well as the convenience of accessing the platform at any time, from any computer.

In response to the evolving demands of virtual and blended education, the virtual laboratory promotes the integration of e-learning strategies. Moreover, acknowledging the necessity of customized pedagogical tools, the platform allows instructors to create their own theoretical materials and manage the simulation environment. Accompanying didactic guides with a constructivist approach further supports the achievement of targeted learning outcomes in courses on mechanism analysis and synthesis.

References

5. Author contributions

License

Copyright (c) 2025 Luz Adriana Mejia Calderón, Carlos Alberto Romero Piedrahita

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

From the edition of the V23N3 of year 2018 forward, the Creative Commons License "Attribution-Non-Commercial - No Derivative Works " is changed to the following:

Attribution - Non-Commercial - Share the same: this license allows others to distribute, remix, retouch, and create from your work in a non-commercial way, as long as they give you credit and license their new creations under the same conditions.

2.jpg)