DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.16707Published:

2021-09-30Issue:

Vol. 23 No. 2 (2021): July-DecemberSection:

Research ArticlesCommodity, Immunity, and Struggle

(Re)visiting Senses of Community in ELT

Mercancía, inmunidad y lucha

Keywords:

communities, decolonial research, English teacher education, identities (en).Keywords:

comunidades, investigación decolonial, formación de profesores de inglés, identidades (es).Downloads

References

Albán, A. (2014). Arte, docencia e investigación. In M. E. Borsani (Ed.), Los desafíos decoloniales de nuestros días: pensar en colectivo (1st ed., Vol. 1) (pp. 151-173). Editorial de la Universidad Nacional del Comahue. http://www.ceapedi.com.ar/imagenes/biblioteca/libreria/332.pdf

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origins and spread of nationalism. Verso.

Archanjo, R., Barahona, M., & Finardi, K. R. (2019). Identity of foreign language pre-service teachers to speakers of other languages: Insights from Brazil and Chile. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 1(21), 62-75. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.14086 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.14086

Arnett, J. J. (2002). The psychology of globalization. American Psychologist, 57(10), 774-783. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.10.774 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.57.10.774

Artundaga, S. (2013). Process Writing and the Development of Grammatical Competence. HOW Journal, 20, 11-35. https://www.howjournalcolombia.org/index.php/how/article/view/21

Barragán, D. (2015). Las comunidades de práctica: hacia una reconfiguración hermenéutica. Franciscanum, 163 (57), 155-176. https://doi.org/10.21500/01201468.699 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21500/01201468.699

Bedoya-González, J. R., Betancourt-Cardona, M. O., & Villa-Montoya, F. L. (2018). Creación de una comunidad de práctica para la formación de docentes en la integración de las TIC a los procesos de aprendizaje y enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 23(1), 121-139. https://dx.doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v23n01a09 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v23n01a09

Bonilla, C. A., & Tejada-Sánchez, I. (2016). Unanswered questions in Colombia’s language education policy. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 18(1), 185-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.51996 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.51996

Castro, A. & López, S. (2014). Communication Strategies Used by Pre-Service English Teachers of Different Proficiency Levels. HOW Journal, 21(1), 10-25. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.21.1.12 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19183/how.21.1.12

Copland, F., Garton, S., & Burns, A. (2014). Challenges in teaching English to young learners: global perspectives and local realities. TESOL Quarterly, 48(4), 738-762. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.148 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.148

Correa, D., & Domínguez, C. (2014). Using SFL as a tool for analyzing students’ narratives. HOW Journal, 21(2), 112-133. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.21.2.7 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19183/how.21.2.7

Chilisa, B. (2012) Indigenous Research Methodologies. SAGE.

Deng, L., Zu, G., Xu, Z., Rutter, A., & Rivera, H. (2018). Student Teachers’ Emotions, Dilemmas, and Professional Identity Formation Amid the Teaching Practicums. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 27(6), 441-453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-018-0404-3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-018-0404-3

Díaz-Maggioli, Gabriel. (2004) Teacher-centered professional development /Alexandria, Va.Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Enever, J., & Moon, J. (2009). New global contexts for teaching primary ELT: Change and challenge. In: Enever, Moon & Raman (Eds.). Young Learner English Language Policy and Implementation: International Perspectives (pp. 5-23). Garnet.

Eren, A. (2014). Relational analysis of prospective teachers’ emotions about teaching, emotional styles, and professional plans about teaching. The Australian Educational Researcher, 41, 381-409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-013-0141-9 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-013-0141-9

Escobar, A. (2018). Otro posible es posible: Caminando hacia las transiciones desde Abya Yala/ Afro/Latino-América. Ediciones desde abajo.

Escobar, W. Y., & Evans, R. (2014). Mentor texts and the coding of academic writing structures: A functional approach. HOW Journal, 21(2), 94-111. DOI: https://doi.org/10.19183/how.21.2.6

Esposito, R. (2012). Communitas. Origen y destino de la comunidad. Amorrortu.

Fandiño-Parra, Y., Ramos-Holguín, B., Bermúdez-Jiménez, J., & Arenas-Reyes, J. C. (2016). Nuevos discursos en la formación docente en lengua materna y extranjera en Colombia. Educación y Educadores., 19(1), 46-64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5294/edu.2016.19.1.3

Farias, M., & Obilinovic, K. (2009). Building communities of interest and practice through critical exchanges among Chilean and Colombian novice language teachers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 11, 63-79. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.154 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.154

Fortier, C. (2017).Unsettling Methodologies/Decolonizing Movements. Journal of Indigenous Social Development. 6, (1), 20-36 https://umanitoba.ca/faculties/social_work/media/V6i1-02_fortier.pdf

García, P., Sagre, A., & Lacharme, A. I. (2014). Systemic functional linguistics and discourse analysis as alternatives when dealing with texts. PROFILE, Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 16(2), 101-116. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n2.38113 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n2.38113

Gómez-Sará, M. M. (2016). The Influence of Peer Assessment and the Use of Corpus for the Development of Speaking Skills in In-Service Teachers. HOW Journal, 23(1), 103-128. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.23.1.142 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19183/how.23.1.142

Higgins, C. (2012). The formation of L2 selves in a globalizing world. In C. Higgins (Ed.) Identity formation in globalizing contexts: language learning in the new millennium. (pp. 1-17). Library of Congress Cataloguing-Publications Data. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110267280.1

Hutchinson, S., Fenton-O’Creevy, M., Goodliff, G., Edwards, D., Hartnett, L., Holti, R., & Way, L., (2014). An invitation to a conversation. In E. Wenger-Trayner, M. Fenton O'Creevy, S. Hutchinson, C. Kubiak, & B. Wenger-Trayner (Eds.). Learning in landscapes of practice: Boundaries, identity and knowledgeability in practice-based learning. (pp. 1-9). Routledge. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315777122-1

Jing, H., & Benson, P. (2013). Autonomy, Agency and Identity in Foreign and Second Language Education. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics (Quarterly), 36(1), 007-028. https://doi.org/10.1515/cjal-2013-0002 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/cjal-2013-0002

Kaltmeier, O. (2012). Hacia la descolonización de las metodologías: reciprocidad, horizontalidad y poder. In S. Corona, & O. Kaltmeier (Eds.) En diálogo. Metodologías horizontales en ciencias sociales y culturales (pp. 25-55). Gedisa.

Kincheloe, J. L., McLaren, P., Steinberg, S. R., & Monzó, L. (2017). Critical pedagogy and qualitative research: Advancing the bricolage. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (5th ed.) (pp. 235-260). Sage.

Kovach, M. (2018) Doing indigenous methodologies: A letter to a research class. In: Denzin & Lincoln (Eds.). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 213-234). Sage.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991): Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. CUP. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Larrosa, J. (1995). Tecnologías del yo y educación. In J. Larrosa (Ed.), Escuela, Poder y Subjetivación (pp. 259-327). Ediciones de la Piqueta.

Leavy, P. (2009). Methods meets arts. Arts-Based Research Practice. The Guilford Press.

Liceaga, G. (2013). El concepto de comunidad en las ciencias sociales latinoamericanas: apuntes para su comprensión. http://www.cialc.unam.mx/cuadamer/textos/ca145-57.pdf

López, F., & Cortez, N. (2016). La relación entre comunidades imaginadas e inversión en alumnos Multilingües. Zona Próxima, 25,103-117.

Marulanda-Ángel, N. L., & Martínez-García, J. M. (2017). Improving English Language Learners’ Academic Writing: A Multi-Strategy Approach to a Multi-Dimensional Challenge. GIST – Education and Learning Research Journal, 14, 49-67. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.367 DOI: https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.367

Mignolo, W., & Walsh, K. (2018). On Decoloniality. Concepts Analytics Praxis. Duke University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822371779

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd edition.). SAGE.

Mills, K., & Chandra, V. (2011). Microblogging as a literacy practice for educational communities. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 55(1), pp. 35-45. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.541.4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.54.1.4

Miñana-Biasco, C., & Rodríguez, J. G. (2002). La educación en el contexto neoliberal. http://www.humanas.unal.edu.co/red/files/3112/7248/4191/Artculos-eduneoliberal.pdf

Muñoz-Polit, M. (2009), Emociones, sentimientos y necesidades. Una aproximación humanista. https://b-ok.lat/book/11891155/d9f737?id=11891155&secret=d9f737

Muñoz-Julio, W., & Ramírez-Contreras, O. (2018). Transactional Communication Strategies to Influence Pre-service Teachers’ Speaking Skill. GIST – Education and Learning Research Journal, 16, 33-55. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.424 DOI: https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.424

Norton, B. (2017). Learner investment and language teacher identity. In G. Barkhuizen (Ed.), Reflections on language teacher identity research. Routledge.

Omidvar, O., & Kislov, R. (2013). The evolution of the communities of practice approach: Toward knowledgeability in a landscape of practice—An interview with Etienne Wenger-Trayner. Journal of Management Inquiry. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492613505908

Ortiz-Ocaña, A., & Arias-López, M. I. (2019). Hacer decolonial: desobedecer a la metodología de investigación. Hallazgos, 16(31), 147-166. https://doi.org/10.15332/s1794-3841.2019.0031.06 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15332/s1794-3841.2019.0031.06

Oviedo-Gómez, H. H., & Álvarez-Guayara, H. A. (2019). The contribution of customized lessons with cultural content in the learning of EFL among undergraduates. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 1(21), 15-43. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.11877 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.11877

Phillipson, R. (2012). English from British empire to corporate empire. Sociolinguistic Studies, 5(3), 441-464 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.v5i3.441

Posada-Ortiz, J. (2019). Patterns of regularity, stability and interdependence in research related to communities in ELT. Studies in English Language Teaching, 7(2), 195-212. https://doi.org/10.22158/selt.v7n2p195 DOI: https://doi.org/10.22158/selt.v7n2p195

Posada-Ortiz, J., & Garzón-Duarte, E. (2014). Autobiographies: a Tool to Depict English Language Learning Experiences. GIST – Education and Learning Research Journal, 18, 161-179. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.447 DOI: https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.447

Quintero, L. M. (2008). Blogging: A way to foster EFL writing. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 10, 7-49. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.96 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.96

Richardson, L. (2001). Poetic representations of interviews. In J. Gubrium & J. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research: context and method (pp. 876-891). SAGE. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412973588.n50

Rivera-Cusicanqui, S. (2010). Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: una reflexión sobre prácticas y discursos descolonizadores. Tinta Limón.

Robayo-Torres, A. L. (2015). Subjetividades docentes en la universidad pública colombiana. Comunidades de práctica a propósito de sus narraciones. Revista Colombiana De Educación, 1(68), 229.263. https://doi.org/10.17227/01203916.68rce229.263 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17227/01203916.68rce229.263

Romm, N. R. A. (2015). Conducting Focus Groups in Terms of an Appreciation of Indigenous Ways of Knowing: Some Examples from South Africa [62 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(1), Art. 2, http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/2087/3730

Saavedra-Jeldres, P. A., & Campos-Espinoza, M. (2018). Combining the strategies of using focused written corrective feedback: a study with upper-elementary Chilean EFL learners. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 20(1), 79-90. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.12332 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.12332

Salamanca-González, F. O. (2015). Personal Narratives: A Pedagogical Proposal to Stimulate Language Students’ Writing. HOW Journal, 22(1), 65-79. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.22.1.134 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19183/how.22.1.134

Salas, M. (2015). Developing the metacognitive skill of noticing the gap through self-transcribing: The case of students enrolled in an ELT education program in Chile. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 17(2), 260-275. https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a06 DOI: https://doi.org/10.14483/udistrital.jour.calj.2015.2.a06

Santos, B. de S. (2018). The end of the cognitive empire. The coming of age of epistemologies of the South. Duke University Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478002000

Thomas, A. (2008). Community, culture, and citizenship in Cyberspace. In J. Coiro, J., C. Lankshear, M. Knobel, M. & D. J. Leu, (Eds.), Handbook of research on new literacies (pp. 671-693). Routledge.

Tonnies, F. (1947). Comunidad y sociedad. Losada.

Torres, A. (2013). El retorno a la comunidad. CINDE.

Ubaque, D. F., & Pinilla, F. (2018). Exploring Two EFL Teachers’ Narrative Events Regarding Vocabulary Teaching and Learning. HOW Journal, 25(2), 129-147. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.2.400 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.2.400

Vanegas-Rojas, M., Fernández-Restrepo, J. J., González-Zapata, Y. A., Jaramillo-Rodriguez, G., Muñoz-Cardona, L. F., & Ríos-Muñoz, C. M. (2016). Linguistic Discrimination in an English Language Teaching Program: Voices of the Invisible Others. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura 21(2), 131-149. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v21n02a02 DOI: https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v21n02a02

Vasilachis de Gialdino, I. (2009). Los fundamentos ontológicos y epistemológicos de la investigacion cualitativa [92 parrafos]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(2), Art. 30. http://www.ustatunja.edu.co/cong/images/curso/IRENE_VASILACHIS_DE_GIALDINO.pdf

Walker, R. (2010, August 27). Sarmy Australian Southern Territory Resource Centre. https://www.sarmy.org.au/Resources/Articles/reforming-society/Eternity-Now-Aboriginal-Concepts-of-Time/

Wilson, Shawn (2008). Research Is Ceremony:Indigenous Research Methods. Fernwood Publishing.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Recibido: 27 de julio de 2020; Aceptado: 10 de agosto de 2021

Abstract

This article comprises part of a broader doctoral research project that seeks to explore the senses of community of four English language pre-service teachers (ELPTs) of a public university in Bogotá, Colombia. This study used a relational methodology that introduces an interepistemic dialogue between mainstream research and the Indigenous Research Paradigm. The data collection process was carried out through five sessions jointly agreed upon and designed with the participants. The main data collection instruments were autobiographies, which were a joint construction, and transcripts of the sessions. The research results show that the university, the English language teacher education program (ELTEP) and the practicum, among others, are part of a constellation of communities of fear or communities that represent a challenge. It was concluded that it is possible to understand the constellation of fear through an alternative theoretical framework that includes community as commodity, as immunity, and as struggle. This study contributes to research trends that seek to privilege the research participants’ voices and offers a different way to approach communities in ELT.

Keywords

communities, decolonial research, English teacher education, identities.Resumen

Este artículo forma parte de un proyecto más amplio de investigación doctoral que busca explorar los sentidos de la comunidad de cuatro futuros docentes de inglés de una universidad pública en Bogotá, Colombia. El estudio utilizó una metodología relacional que introduce un diálogo interepistémico entre la investigación tradicional y el Paradigma Indígena de Investigación. El proceso de recolección de datos se llevó a cabo mediante cinco sesiones que fueron acordadas y diseñadas en conjunto con los participantes. Los principales instrumentos de recolección de datos fueron las autobiografías, que fueron una construcción conjunta, y las transcripciones de las sesiones. Los resultados de la investigación muestran que la universidad, el programa de formación de docentes de inglés (ELTEP) y la práctica pedagógica, entre otros, son parte de una constelación de comunidades de miedo o comunidades que representan un desafío. Se concluyó que es posible entender la constelación del miedo a través de un marco teórico alternativo que incluye a la comunidad como mercancía, inmunidad y lucha. Este estudio contribuye con la investigación que busca privilegiar la voz de los participantes y ofrece una manera diferente de aproximarse a las comunidades en ELT.

Palabras clave

comunidades, investigación decolonial, formación de profesores de inglés, identidades.Introduction

This article is the result of a wider doctoral project framed within a line of research whose areas of interest are EFL (English as a foreign language), power, and inequity. This research interest seeks to analyse, study, and understand the interface of learning-teaching experiences of English with identity, power, and inequality in myriad sociocultural contexts inside and outside the ELT (English language teaching) classroom (DIE-UDFJC, n.d.). The research topic derives from our work as teacher educators interested in researching with a decolonial perspective.

The purpose of this article is, then, to describe a study that explores the community senses (otherwise) made by a group of ELPTs, so we can deconstruct the term ‘community’ from their perspective. By ‘otherwise’, we mean “other ways of thinking, sensing, believing, doing and living” (Mignolo and Walsh, 2018 p. 4).

Based on a search conducted on the main ELT journals in Colombia, using the key words ‘community’, ‘communities’, ‘communities of practice’, ‘teacher education’ and ‘ESL/EFL’, the use of three terms was found as a general tendency: Communities of Practice (CoPs), Imagined Communities (ICs), and TCs (Target Communities). There was also a wide variety of communities mentioned such as educational, teaching communities, teacher professional communities, academic communities, learning communities, and a based-learning community ( Posada-Ortiz, 2019 ). The aforementioned terminology is mostly adopted from white European authors and is rarely clearly defined or problematized. The fact that the majority of these terms are imported might evidence a matrix of knowledge that privileges the hierarchy of knowledge, its organization, its legitimacy, and its circulation within the “global order” ( Albán, 2014 ).

In social approaches to language learning, community has been addressed by the notion of CoPs, a concept developed through a three-phase process:

With the first phase of theorising (Lave and Wenger, 1991) we are predominantly looking at the process of learning within communities; the second phase (Wenger, 1998) involves switching to the notion of [CoP] as such and describing boundaries and identities within and across them; and the third phase (Wenger, 2009, 2010; Wenger-Trayner, E. & Wenger-Trayner, B., in preparation) entails returning to the notion of learning, but locating it within complex systems of interconnected practices. (Omidvar, and Kislov, 2013, p.11)

Lave and Wenger’s impact (1991) , and therefore the first phase of theorizing, led university educators to think about the need to create CoPs to help professionals develop the practice of their specific careers. However, this need/impact “obscures the multiple communities to which students belong to and the likelihood that their eventual destinations lie outside the academic community” ( Hutchinson et al. , 2014 , p. 2).

Poststructuralist perspectives on ELT have used the concept of imagined communities (ICs), a term first coined by Anderson (1983) referring to “groups of people, not immediately tangible and accessible, with whom we connect through the power of imagination” ( Norton, 2017, p. 8). In this conceptualization, identity is associated with investment, and it is believed that, if students invest in learning English, they do so in the hope that, by belonging to the English-speaking community, their life will improve via accessing better jobs and being able to communicate in the global village. However, not all students seek to learn English or dream of communicating in the global village using this language; in their imagination, there are other languages: not only Western European, but also Eastern non-European ones such as Japanese ( López and Cortéz, 2016 ).

Target Communities (TCs) refer to “the idea of a mostly cohesive group of people who speak a (standard) language in relatively homogeneous ways, and whose cultural practices likely differ significantly from those who study the target language of that community” ( Higgins, 2012, p. 5). In this view, the ELPTs are constructed within the dichotomy of ‘native vs. non-native’ ( Higgins, 2012 ).

The analysis of the studies on TCs that appear in Colombian ELT journals shows that there are three major areas. Firstly, the effects that the dichotomy of ‘native vs. non-native’ has on ELPTs’ socio-affective factors, fear of negative evaluation, communication apprehension, devaluation of their language variation, and the construction of the ELPT’s identity in terms of English proficiency (Archanjo et al., 2019. Vanegas-Rojas et al., 2015). Secondly, the improvement of ELPTs’ linguistic, communicative, and intercultural skills, as well as of their ability to use Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), so that they can perform well in the academic community (Oviedo-Gómez and Álvarez-Guayara, 2019. Muñoz-Julio and Ramírez-Contreras, 2018;

Saavedra-Jeldres and Campos-Espinoza, 2018. Marulanda and Martínez, 2017. Gómez-Sará, 2016 . Salas, 2015 . Salamanca-González, 2015. García et al , 2014 . Escobar and Evans, 2014 . Castro and López, 2014. Correa and Domínguez, 2014 . Artundaga, 2013 . Quintero, 2008). Thirdly, the search for a collaborative job between in-service and pre-service teachers to resist hegemonic policies ( Ubaque and Pinilla, 2018 ; Kuhlman, 2010).

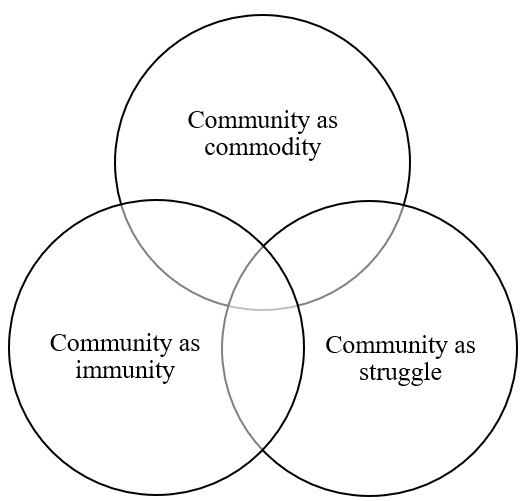

The idea of creating CoPs to develop English teacher competencies seems to be the focus of the studies mentioned above. That also seems to be the reason why CoPs have been instrumentally used to develop ELPTs’ pedagogical, critical thinking, linguistic, and technological skills ( BedoyaGonzález et al., 2018. Farias and Oblinovic, 2009 ), as a key concept in ELTEPs (Barragán, 2015. Fandiño-Parra et al., 2016 ) and as an important element to introduce educational innovations ( Robayo-Torres, 2015 ). It seems that the use of CoPs has been instrumentalized, and the potential of the third phase of the conceptualization of CoPs may still be unknown. Therefore, we think that the term ‘community’ in ELT can be conceptualized beyond the modern concepts described above. In order to decolonize the static and normalized senses of community associated with TC, CoPs, and ICs, we intend to present alternative understandings of community (e.g., commodity, immunity, and struggle) drawing on both philosophy ( Esposito, 2012 ) and Latin American sociology ( Liceaga, 2013 ). An alternative framework to conceptualize communities in ELT enables “political and ethical transformations” ( Mignolo, 2001, p.11 ) since it allows imagining English teacher education beyond global designs. It also allows “to craft new forms of analysis” (Escobar, 2007, p. 191) and, last but not least, to move away from a modern perspective that recognizes Western epistemology as the only valid one.

Alternative and complementary theoretical framework

Community as commodity

“[E]conomic globalisation has resulted in the widespread use of English and many governments believe it is essential to have an English-speaking workforce in order to compete” (Copland et al., 2014, p. 738). This fact is derived from “the continuing neoliberalist strategy of the ‘free market’ global economy moving towards increased economic liberalization via corporations, governments and international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the World Bank (WB)” (Enever and Moon, 2009, p. 6).

This neoliberalist tendency has led countries such as Colombia to look for competitiveness in the global market by adopting international language policies, among which “an explicit English-dominant foreign language education policy” ( Bonilla and Tejada, 2016, p. 186) has prevailed since 2004. This policy has some consequences in the way the Ministry of Education and the ELTEPs conceive the word ‘community’. For the Ministry of Education (2013), community is the duty of anyone involved in education to be part of academic communities, and of each institution to create CoPs to integrate English teachers. According to Phillipson (2012) , “building communities of practice, of language use and language learning” (para. 3) is part of the many threads behind the implementation of English as a lingua franca which, in turn, leads to imagining a community ( Anderson, 1983 ) where everybody is affiliated by speaking English. For ELTEPs, CoPs become the instrument to improve linguistic, technological, pedagogical, and research skills; they are therefore an important category to be included in the design of ELTEPs ( Fandiño-Parra et al., 2016 ).

In this way, community becomes a commodity governed by standards that ELPTs must reach, demonstrating the linguistic and pedagogical competencies necessary to be accepted by the academic community. The ELTEPs must be sufficiently capable of graduating students who have attained such proficiency. A ‘trap’ that many teacher educators have already begun to question. The commodification and the uncritical use of the community ( Torres, 2013 ) deserve a reflection on the origin of the term, as well as on the danger of maintaining a static and monolithic vision of community, something we shall explore below.

Community as immunity

Tonnies (1947) originally coined the term ‘community’ as a metaphysical union of bodies or blood ( Liceaga, 2013 ). Community is associated with what is enduring, stable, and authentic, as well as with the territory. This means being associated with common property and with the connection of individuals who share a common identity. This concept prevailed in philosophy during the twentieth century until it was deconstructed ( Esposito, 2012 ).

Esposito’s ideas - derived from his etymological analysis of the word ‘community’ - deconstruct the notion of community based on the common property and pre-established identity that connect members. This identity, in a sense, precedes community and gives it substance ( Esposito, 2012 ). For Esposito, common property and identity become organizing axes where “politics and life intersect in power relations and where the thinking and acting of human subjectivity is situated and placed” (Hernández, 2018, p. 215).

Therefore, community entails political power that homogenizes and denies the individual. This denial of individuality and heterogeneity implies the fear of social survival; that is, to become part of the community, we sometimes have to give up our subjectivity to become a social being, and we give it up because of fear of social death, nonexistence, and not being accepted. In this way, Esposito (2012) presents the community as the place that prevents us from developing a full identity because, in a community, identity is predetermined and substantial. This is the reason why a community harbours fear. Not being accepted or adhered to a community and adopting a community identity might show that we are not able to love each other; for this reason, people seek to be part of a group. In this sense, community entails fear. This is how Esposito talks about a community of death or a community of fear: the death of subjectivity and the fear of dying.

In this sense, Esposito invites us to question the governmentality that produces human subjectivity. In such production process, it is decided who is ‘inside’ or ‘outside’ of a community, who is ‘included’ or ‘excluded’, and who ‘deserves’ or ‘does not deserve’ to live; that is, questioning the immunity of the community that allows some to belong or not depending on their adoption of the community identity. Esposito’s main questions are: How to belong to a community without losing our individual identity? How to avoid an immunity that leads to death and fear? How to avoid an immunity that legitimizes power? These questions are particularly relevant in the context of the educational policies related to teacher education in Colombia, especially when there is such pressure over teacher educators and ELPTs to belong to CoPs and academic communities.

Community as struggle

Esposito’s ideas are derived from his etymological analysis of the word ‘community’ and from the reflection on coexistence as an intrinsic condition of humankind. We are always together with other human beings. However, we are not only with other human beings; we also live with nature and are also surrounded by the spirit of those who have died. This is an aspect that, according to Escobar (2018) , is not considered by the global capitalist societies. For this reason, the notion of community developed by the sociologist Liceaga is quite relevant and complementary to Esposito’s ideas. Liceaga (2013) developed a concept of community associated with indigenous and rural people in Latin America, whose form of organization, way of life, and worldview differs from Western modernity. Community is a word of struggle that refers simultaneously to tradition and the future, to what it was, to what it is and what it could be ( Liceaga, 2013 ). For Latin Americans, community is a word of struggle associated with indigenous and rural people, groups that have suffered dispossession and violence derived from the processes of land appropriation initiated during the Spanish conquest. Community refers to tradition because it is about keeping others’ worldviews alive, and it also refers simultaneously to the past, present, and future because time is not linear in ancestral traditions time ( Walker, 2010 ). In a nutshell, the sense of community in Liceaga’s concept is integrative and dynamic: integrative because it includes other worldviews, the worldview of indigenous and country people, for whom not only do we live together with other people, but also with nature; and dynamic because it refers to our past, present, and future on this earth.

Decolonial doing: exploring alternative ways of carrying out research

Although social anthropology and poststructuralist, postmodern, and postcolonial theories in the 1980s and 1990s have questioned researchers’ construction of knowledge and new trends (just as the Narrative Turn has tried to privilege research participants’ voice), it is necessary to decentralize the ways in which research is conducted ( Kaltmeier, 2012 ). Firstly, because, within the qualitative paradigm, some trends derived from postpositivism are in contention ( Kincheloe et al. , 2017 ). Secondly, these trends have been produced within the Western tradition ( Kaltmeier, 2012 ). For this reason, we draw on decolonial doing (understood as an alternative way to conduct research), recognizing the existence of traditional approaches and paradigms but assuming and, above all, defending the fact that there are other ways to conduct research and produce knowledge ( Ortiz and Arias, 2018 ). This is how we fused elements of Narrative Inquiry (NI) and Narrative Pedagogy (NP) with the Indigenous Research Paradigm (IRP).

NI, NP, and the IRP use narratives to understand people’s experiences and what people learn from them. Narratives then constitute a first-hand tool to gain knowledge about how people learn directly from the ones implied in the process, in this case, the ELPTs, and the researchers. Narratives promote the introduction of relationality, a key concept in the IRP that entails an ontology, an epistemology, and an axiology ( Wilson, 2008 ). A relational ontology “emphasizes relations with people, with the environment/land, with the cosmos, and with ideas” (Chilisa, 2012, p. 113). Because relationships with people are very important in the community life of indigenous people, in a relational methodology that follows a relational ontology, the researcher must create an environment in which all parties can connect with each other ( Chilisa, 2012 ). The creation of the environment was achieved through joint decisions that included the selection of meeting places to carry out work sessions, as well as an agreement that the topics were to be written in the form of autobiographies. Relational epistemologies are opposed to the individual ways of knowing that characterize Euro-Western epistemologies ( Chilisa, 2012 ) and can be defined as “processes of people collectively constructing their understandings by experiencing their social being in relation to others” ( Romm, 2015, par. 1).

Finally, a relational axiology “is guided by the principles of accountability, responsibility, respectful representation, reciprocal appropriation and rights and regulations” ( Chilisa, 2012, p. 117). These principles refer to the researcher’s ability to create a relationship of trust with the participants, avoiding extractivism ( Santos, 2018 ) and, above all, eschewing the appropriation of rights over the knowledge produced by recognizing that such knowledge is a joint production with all those involved in the research process (Fortier, 2017).

Therefore, trust was created from the beginning by clearly explaining the research process and showing respect for joint decisions. These decisions also included data analysis, which we carried out together and represented through poems, a process that will be explained below.

Methodology

The research design of this study is framed within the qualitative paradigm and follows a decolonial perspective. For this reason, and considering that the way we name the world affects our practices ( Rivera-Cusicanqui, 2010 ), the reader will find that we propose and explain some words such as research collaborators instead of participants, and that we call the process of data collection ‘interaction to exchange and generate knowledge’. The data results are displayed through poems.

Context and research collaborators

The verb ‘collaborate’ is derived from the Latin collaborare which means working with someone else. In this sense, a collaborator is someone ‘one works with’. Since the research process described in this article represents a joint effort, participants will be called ‘research collaborators’. We would also like to acknowledge all authors we read as research collaborators, whose contributions made this proposal possible to develop. Finally, we would also like to add that teachers and classmates in the doctoral studies are also research collaborators.

As for the ELPTs, this research project was carried out with Marcela, Luna, Santiago, Omar, and Camilo. However, due to length constraints, we will only share Marcela’s autobiography. She wrote in her blog:

My name is Marcela. I am 19 years old and I am studying my 6th semester in an English Teacher Education Programme at a state University in Bogotá, Colombia.

The ELTEP has a high socio-cultural, reflective, critical-humanistic, and investigative component that seeks to re-signify knowledge, which contributes to improving quality of life. The main purpose of the ELTEP is for ELPTs to take an active role in their learning process and learn, relearn, invent, and express their experiences to become intellectuals in constant change (Proyecto Curricular de LEBEI, 2011). For a more detailed description of the ELTEP, see the work by PosadaOrtiz and Garzón-Duarte (2014) .

Autobiographies

An Autobiography is a ‘form of narrative’ ( Posada-Ortiz and Garzón-Duarte, 2019 ). Using autobiographies in initial teacher education is a pedagogical practice that allows producing and mediating certain forms of subjectivation, in which the one who reflects, modifies, and analyses their own experience is the one who writes it, that is, an autobiography is an instrument that does not deal with objectified informants; instead, the participants become talking subjects and confessors of a truth that they themselves produce and about which they reflect ( Larrosa, 1995 ). Understanding autobiographies in this way allows us to deviate from the epistemology that privileges the subject-object relationship and to configure a philosophy that focuses on the subject-subject relationship, that is, on a self with another self ( Ortiz-Ocaña and AriasLópez, 2018 ).

These characteristics are consistent with the epistemology, ontology, and relational axiology of the proposed relational-decolonial doing. We argue that, by jointly deciding how, when, and where the autobiographies are written, a heterarchical process takes place while recognizing the collaborators’ subjectivity; the collaborators, in turn, recognize themselves in their writing processes. We decided together that the autobiographies would be published in blogs. We ended up staging five work sessions.

Each session was developed following a protocol to infuse a practice of respect. This protocol was discussed, modified, and accepted by the research collaborators, and it consisted of 1) a mindfulness exercise to quieten the mind while being aware of the present moment, 2) a common agreement about the topic we were going to write about in our autobiographies, 3) an individual reading of what we had written, and 4) questions about those aspects we wanted to know more in-depth. We sat in a circle and used a symbol to give the floor when someone was going to speak. The person who was speaking could not be interrupted. We did learn to listen to each other. The questions we wanted to ask could only be asked at the end of each reading. The five sessions were videotaped and transcribed.

Interaction to exchange and generate knowledge

We decided to name this section of the article ‘interaction’ in order to exchange and generate knowledge because we interacted, negotiated, conscientiously listened to each other, and interpreted together the ‘knowledges’ we had produced collaboratively.

At this point, it is necessary to recount the general process through which information was collected. The ELPTs wrote autobiographies, which were shared in sessions in which we listened to each other and asked about/for details. The autobiographies were published in blogs that were modified after each session. All of this was collectively agreed upon in a process of constant negotiation.

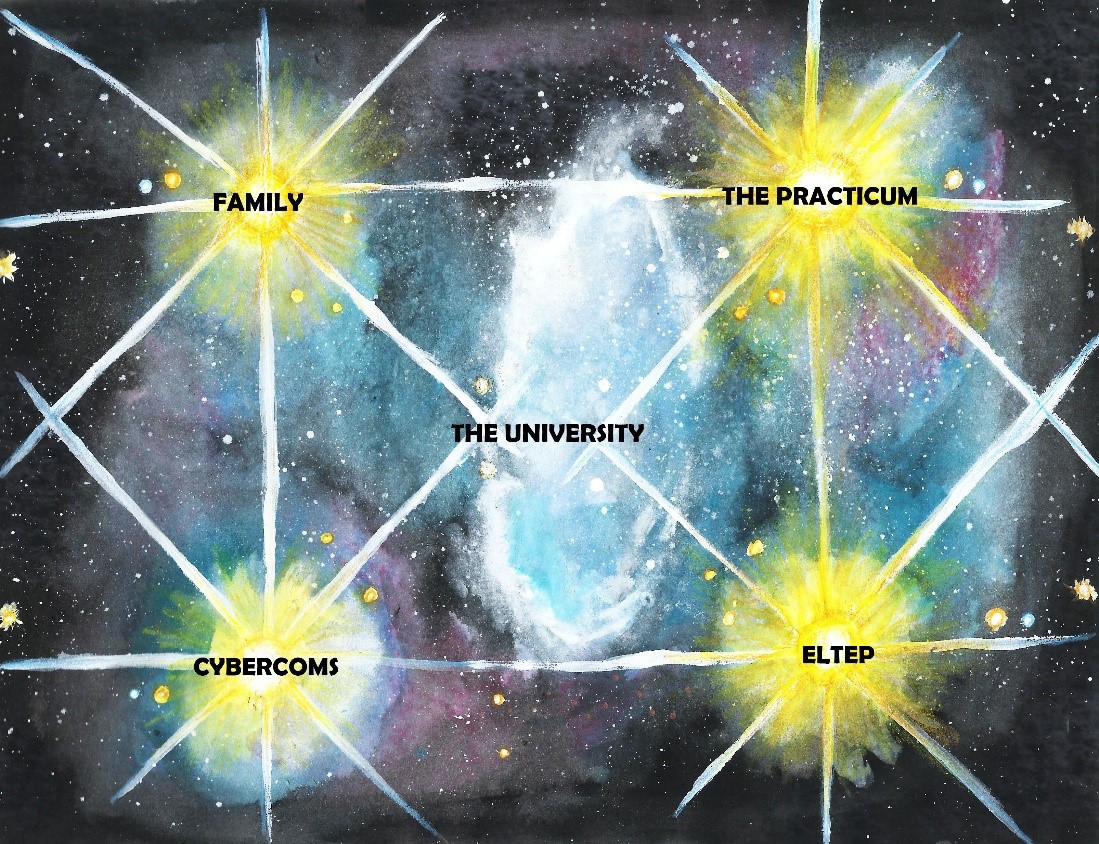

After the last session, and at the request of the ELTPs, we held another session in which we explained how to analyze the data. We followed Miles et al. (2014) , for whom the information obtained through words should be analyzed through coding and pattern coding. For the coding stage, we used an in vivo approach, which means that we used words and phrases from “the participants’ own language in the data record as codes” ( Miles et al. , 2014 , § 4). This is how the ELPTs coded the communities they belong to under the names of family, university, ELTEP, practicum, religious groups, and cybercommunities.

The above led to a process of community coconstruction faithful to the principle of relationality, a process that sought to recognize participants’ subjectivities and that defended cohesion in diversity and not in unity. In another session, we all agreed that we were going to present these categories through ‘poetic representation’, which provides “researchers an opportunity to write about, or with people in ways that honour their speech styles, words, rhythms, and syntax” ( Richardson, 2001, p. 880). Poetic representation invokes “a snippet of human experience… it can help the researcher evoke different meanings from the data… and help the audience receive the data differently.” (Leavy, 2009 p. 64). Finally, the convergence of word, sound, and space that poems imply is key to the construction and articulation of social meaning ( Leavy, 2009 ).

Due to length constraints, we will only show some poem extracts. In what follows, we will present the different communities that Marcela envisioned for herself, as well as their defining features.

Results: presenting the senses of community

In this section, we will present the three senses of community derived from the reading of the poems that were written together with Marcela. These senses are community as commodity, immunity, and struggle intertwined with fear, which appears to be the common element. People might think that fear is a negative feeling. However, fear is also presented as something positive, because fear leads Marcela to look for different paths to not only belong to a given community, but also to improve herself as an agent of her own learning and decision-making process.

A story about a language-student teacher

Marcela is llanera and rola and she feels that she does have characteristics of both origins and none at the same time. She has a bicultural identity entailing both local and global identities that give her “a sense of belonging to a worldwide culture” (Arnett, 2002, p. 777), as it can be seen in the first part of the poem, where she describes her regional, local, and global identities.

You may wonder why I chose this path

I will start from the very beginning

Figure 1: Alternative theoretical framework

When my mother left her hometown

And inspired the rest of her family Everyone moved to Bogotá as well.

My father and mother met in Bogotá

Then I was born in this city

Feeling at odds

Not being from here or from there

Although curious about both cultures

And other cultures as well

Marcela experiences a painful predicament since she feels she does not fit anywhere. Her mother wanted her to study accounting, but Marcela loved social sciences and hated numbers. Fortunately, she was supported by her father and enrolled in the ELTEP.

Dealing with high expectations

That your family has about you

It’s something that scares you

Sometimes they just say

How ironic this is

Although I don’t live with my father I resemble him in that I love

Social sciences instead of numbers

That is enough to upset my mother

However, Marcela’s most painful experience was coping with not being considered an intelligent person or worthy of belonging to the academic community due to her religious beliefs. Marcela states that sometimes she has to accept ideas she does not agree with. As Esposito (2012) puts it, fear leads her to deny her subjectivity to be accepted by the academic community. However, this fear is transformed into courage when she realizes that, although she pretends to agree with others, deep inside, her ideas remain firm. In this sense, Marcela’s classmates and teachers create a community as immunity in which believers have no place.

Pressure because of my beliefs

Forced to say or defend things

I do not agree with Can a believer be?

Someone who thinks?

Can a believer be? Taken seriously? But I laugh

And grow stronger I am a happy

Thoughtful Christian

Here, we glimpse a community in which it is imperative to develop linguistic proficiency that results in fright and annoyance, a side effect of the dichotomy of ‘native vs. non-native’ ( Archanjo et al., 2019. Vanegas-Rojas et al., 2015 ).

I remember my first days at the ELTEP

Sadness, pressure, irritation

Someone little, giant challenge

Stage fright, reading comprehension lack

Also come to my mind

Nevertheless, this side effect also provides Marcela with a new richness; it motivates her to move towards new literacies found in cyberspace, where she has fun and, at the same, time extends her academic persona ( Thomas, 2008 ). This means that Marcela engages in self-initiated cybercommunities through blogs such as Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, where she improves and practices her English in spontaneous, hyperlinked, collaborative, and global environments ( Mills and Chandra, 2011 ).

Feeling dumb speaking English

Made me rehearse before speaking,

Feeling fear speaking English

Made me look for other sources

Not too serious or professional

Such as movies and soap operas

Feeling annoyed by reading in English

Made me look for blogs and popular literature Twitter, Facebook, and entertainment Useful tools for a language learner.

Marcela’s struggle to improve her linguistic competence and fit into the academic community to which she belongs, which also requires her to speak and write well in English, simultaneously represents aspects of community as struggle and as commodity: As struggle, because Marcela seeks to improve her linguistic competence through new technologies and reaffirm herself as a believer, but at the same time as commodity because Marcela’s search to achieve standards implies the neoliberal project as a hidden curriculum.

Being in the middle of her studies represents a dilemma for Marcela, who, although she likes to learn English and would like to convey this feeling to her future students, is not yet sure whether she wants to be an English teacher. According to Deng et al. (2018) , these dilemmas are very common among student teachers “in light of their emergent professional identity formation” (p. 442).

I enjoy learning English

And I want my students to do so

The teaching practicum

Has enriched me a lot

I love my profession

But I am still not sure

Whether I would like to be

An English teacher or not

Marcela believes that her friends have helped her become a stronger person. Marcela is also aware of the influence her teachers will have on her teaching, so, at the university, anyone can learn by interacting with people.

Friends come and go

Each one leaves a footprint

Same is true for teachers

Whose print I will reflect

In every part of who I am

The practicum appears again as fear for Marcela. This fear is the product of a feeling of insecurity that leads her to be afraid of not being a good teacher and not doing things well. This might confirm Eren’s (2014) hypothesis, according to which teachers showing negative emotions might feel that they are less effective; in the case of Marcela, her insecurity towards her first time teaching makes her think that she might not do well as an English teacher. However, the fear she experiences in the practicum also allows her to learn what it means to become an English teacher. One might assert that the practicum is a community where Marcela “theorizes practice and practices theory” (Díaz-Maggioli, 2012, p. 12). This is why she states that this is the place where she really learns what being a teacher means.

The practicum made me fearful

But there is where I learned

What being a teacher

Is really about

In summary, the university, identified by Marcela as a community, encapsulates a community as immunity, where believers have no place; as a struggle, where Marcela seeks to reaffirm herself as to who she really is and seeks to be accepted. The practicum is identified as a community as a struggle since it poses a dilemma for Marcela, who still does not feel confident about wanting to be an English teacher. Finally, we can also see how the academic community in which Marcela moves becomes a commodity as long as it is governed by standards that determine what it means to be a good language teacher.

Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of this research project was to explore the senses of community of a group of ELTPs (otherwise). In order to achieve this purpose, we collectively carried out a relational research process in which we categorized the main communities they belonged to.

Marcela mentioned the university, the ELTEP, her family, the Christians, the practicum, and cybercommunities as the main communities she belongs to. Marcela’s sense of university community is basically that of exclusion, an exclusion derived from her religious faith. This sense of exclusion makes Marcela accept things she does not agree with. This fact turns the university into a community fed by fear: fear of being excluded from a particular group. Fear is what leads Marcela to hide the true ideas that she keeps deep down inside. The ELTEP is also a community nurtured by fear, but, this time, the fear is associated with the dichotomy of ‘native vs. non-native’, thus leading Marcela to feel stage fright, as well as frustrated and dumb, when speaking English. Another community of fear for Marcela is the practicum. When teaching, Marcela feels afraid of failing as a teacher. The practicum also represents the place where Marcela really understands what being a teacher means. However, because Marcela is in the middle of her studies, she experiences an ontological dilemma as well: she is not sure whether she wants to be a teacher. Finally, in cybercommunities, she enjoys a sense of belonging since it is there that she can interact with family and friends in an informal environment. Although fear appears recurrently, this fear does not paralyze Marcela, but rather motivates her to action, to seek to be better, something that she achieves by joining the cybercommunities and extracting the best from her classmates and teachers.

Figure 2: Constellation of communities within the community of fear

In sum, the university, the ELTEP, her family, the Christians, the practicum, and cybercommunities make up the constellation of communities within the community of fear for Marcela, as shown in Figure 2 . Despite the fact that fear is associated with phobias and panic that could cause hesitation and estrangement, it is also an emotion that serves to seek survival ( Muñoz, 2009 ). That is, emotions motivate actions. In Marcela’s case, these actions are manifested in her agentic initiatives through which she “exert[s] control over [her learning and decision-making processes] and give[s] direction to the course of [her life]” (Jing and Benson, 2013, p. 13). This is evident in Marcela’s decision to continue being a Christian despite criticism and to find ways to overcome her English language learning difficulties.

As explained in the alternative and complementary theoretical framework section, the constellation of communities described by the ELPTs can be encapsulated in three main themes such as community as commodity, immunity, and struggle ( Figure 1 ). These three communities are intertwined since, for example, Marcela’s struggle to be accepted at the university and the ELTEP (despite her religious beliefs) hides the action of an academic community that shows itself as immune by not accepting those beliefs.

The community as struggle is present at all times; it is evident in Marcela’s desire to achieve linguistic proficiency so she can meet the expectations of the ELTEP. There is also struggle in Marcela’s search for the affirmation of her identity, a search that takes place not only in the ELTEP, but also in the cybercommunities to which she belongs. Finally, the community as struggle implies the community as commodity because the ELTPs are trapped in an educational model governed by a neoliberal project in which quality control is created through standards and competencies ( Miñana and Rodríguez, 2002 ).

Implications

This study has some implications for ELTEPs. First of all, it is important to recognize that the senses of community of the ELPTs are built on a continuum formed by the present, past, and future of their educational experiences, and that this continuum is key in the construction of their professional identities. This means that it is necessary to acknowledge this process in order to be able to open room for new ecologies in ELTEP’s profiles.

Secondly, considering that the university, the ELTEP and the practicum are fear communities for ELPTs, it is necessary to know and work on the role of fear not only in learning processes, but also in the constitution of the identity and subjectivity of future language teachers.

Providing suitable environments for learning brings forth the need to create mechanisms, so that the education of ELPTs is more associated with a welcoming environment not only governed by the achievement of parameters established by neoliberalism, but also, and more importantly, based on the ELTPs and their particular interests, including their spirituality.

Finally, it is necessary to design research projects that introduce other ways to conduct research and that, more than giving voice, promote mutual listening because, by doing so, we will not only move away from traditional ways of doing research but also from a colonial and adult-centric perspective in which it is adults, represented by the Ministry of Education and scholarship, who determine what young people should be taught and what their research should be about.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Cindy Milena Posada Montoya for her drawing of the constellation of communities.

References

Notes

Metrics

License

Copyright (c) 2021 Julia Zoraida Posada Ortiz, Harold Castañeda Peña

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.