DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.154Published:

2009-01-01Issue:

No 11, (2009)Section:

Research ArticlesBuilding communities of interest and practice through critical exchanges among chilean and colombian novice language teachers

Construcción de comunidades de interés y de práctica mediante intercambios entre estudiantes chilenos y colombianos de un programa de lenguas

Keywords:

conectividad, TICs, docentes en formación, comunidades de práctica (es).Keywords:

Connectivity, ICT, novice language teachers, communities of practice (en).Downloads

References

Brown, D. (1994). Principles of language learning and teaching. New Jersey: Prentice Hall Regents.

Buckingham, (2003). D. Media education. Literacy, learning and contemporary culture. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Cassany, D. (2000) De lo Analógico a lo digital: El futuro de la enseñanza de la composición. Revista Latinoamericana de Lectura, junio, n.2, p.1-11.

Farias, M. (2005). Multimodalidad, Lenguaje y Aprendizajes, Contribuciones Científicas y Tecnológicas, Usach, No 133, 33, p.26-31, Available also at http:// www.usach.cl/VRID/pub

Farias, M. (2008). (unpublised paper). Farias interviews Dr. Nick Hine at the University of Dundee, Scotland. June.

Freire, P. and D. Macedo. (1987). Literacy: reading the word and reading in the world. South Hadley, MA: Bergin and Garvey.

Kress, G. y T. van Leeuwen. (1996). Reading images. The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.

Horwitz, E and D. Young (eds). (1991). Language Anxiety. From theory and research to classroom implications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Mayer, R. (2001). Multimedia Learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

McCarthy, M. (2001). Issues in Applied Linguistics, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mitchell, R. and F. Myles. (2004). Second Language Learning Theories, New York: Oxford University Press.

Quintana, A. and R. Rueda. (2007). Ellos vienen con el chip incorporado. Bogotá: Universidad Distrital FJDC.

Seidlhofer, B. (2003). Controversies in Applied Linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Vandenhorpe, C. (2003). Del papiro al hipertexto. México, DF: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Warschauer, M. (1997). Computer mediated collaborative learning: Theory and practice. The Modern Language Journal, vol. 81, No 4, (Winter, 1997), pp. 470-481.

Wenger, E. (2007). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colomb. Appl. Linguist. J., 2009 vol:11 nro:1 pág:63-79

Research Article

Building Communities of Interest and Practice through Critical Exchanges among Chilean and Colombian Novice Language Teachers

Construcción de comunidades de interés y de práctica mediante intercambios entre estudiantes Chilenos y Colombianos de un programa de lenguas

Miguel Farias

Professor Department of Linguistics and Literature Universidad de Santiago de Chile E-mail: mfarias@usach.cl

Katica Obilinovic

Associate Professor Department of Linguistics and Literature Universidad de Santiago de Chile E-mail: kobilinovic@usach.cl

Abstract

This article reports a collaborative experience between two groups of EFL novice teachers from Chile and Colombia. We explored the potential of a virtual platform and other means of ICT connectivity to create communities of practice and interest by engaging in critical pedagogy activities that allowed the trainees to look at their education from a comparative perspective. Through the creation of blogs, a group of 30 Chilean pre-service teachers, as language learners and language users, were asked particularly to reflect critically on the power of hypertextuality so they could gain an understanding of the (non-neutral) constructedness of texts, to raise their rhetorical awareness both as text producers and text readers, and to develop agency as communicators and not just passive receivers of media messages. We postulated that immediate feedback from peers and opportunities for sharing with real global audiences would promote higher level thinking, communication skills, and deeper understandings of texts. Sample comments taken from responses to a qualitative survey applied to the Chilean participants will be used to illustrate these points.

Key words: Connectivity, ICT, novice language teachers, communities of practice

Resumen

Este artículo reporta una experiencia colaborativa entre dos grupos de docentes en formación inicial en dos programas de formación de docentes de inglés como lengua extranjera en Chile y Colombia. Exploramos el potencial que una plataforma virtual y otros medios de conectividad, usando las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación (TICs), ofrecen en la creación de comunidades de interés y de práctica, al utilizar actividades de la pedagogía crítica que les permitieron a los docentes en formación mirar su educación desde una perspectiva comparativa. A través del uso de blogs, se les pidió a un grupo de 30 docentes en formación inicial, como aprendices y usuarios de inglés como lengua extranjera que reflexionaran en forma crítica sobre el poder de la hipertextualidad con el fin de que comprendieran la construcción no-neutral de los textos, tuvieran una conciencia retórica como lectores y productores de los textos y desarrollaran agency como comunicadores para que no fueran receptores pasivos de los mensajes de los medios. Postulamos que la retroalimentación inmediata de los compañeros y las oportunidades de compartir con audiencias a nivel global promueve el desarrollo de un alto nivel de pensamiento, habilidades de comunicación, y una mayor comprensión de los textos. Ejemplos de comentarios tomados de las respuestas a una encuesta aplicada a los participantes Chilenos se utilizan para ilustrar los puntos claves de este estudio.

Palabras claves: conectividad, TICs, docentes en formación, comunidades de práctica

Introduction

The current demands and contradictions of globalization and the necessary critical reflections on the implications it brings to our lives as citizens and educators set the grounds for innovating our practices. Looking at the individual as a single node in a huge network of varied connections can yield an Orwellian picture of dismay and isolation. Yet, understanding those connections as inherent to human growth (learning) offers the challenge to exploit such connectivity in the best interest of our ideals as educators: to build a better world with social justice for everyone and create learning communities engaged with those ideals.

The field of language education is not alien to these demands, more so when language as discourse is the means by which these networks are constructed and ideals are shared. The new generations of foreign language teaching educators in Latin America, particularly in the teaching and learning of English as foreign or second language, are slowly constructing local practices that detach themselves from imported knowledge coming primarily from the so called hegemonic centers. These practices are made possible through the connectivity that allows us to have network-based projects like the one we are reporting on.

This paper has been divided into two sections. In part I we present the theoretical foundations that support the activities that we carried out with two groups of undergraduate student teachers in an applied linguistics course in Chile during the first semester of 2008. In this part the reader will find three subsections structured around three theoretical concepts: learning within communities of practice, defined by Wenger (2007) as “social participation” (p.4), concepts derived from the Vygotskyan sociocultural model, and the notions of multimodality and hypertextuality. The discussion of these concepts is illustrated with our reflections on aspects of the project. Part II focuses on the qualitative and quantitative findings obtained in the academic project, based on some of these theoretical constructs and illustrated with excerpts from students´ answers to a qualitative survey.

Part I. Some theoretical constructs

Communities of practice

The following quotation summarizes one of Wenger’s assumptions and is self-explanatory: “Meaning – our ability to experience the world and our engagement with it as meaningful – is ultimately what learning is to produce”. (p.4). Wenger’s social theory of learning stems from four dimensions: ‘meaning’, defined as the ability “to experience our life and the world as meaningful” (p.5), ‘practice’, ‘community’, and ‘identity’. We here make reference only to those components of his theory that relate to the experience that we are reporting. Wenger separates ‘learning’ from a ‘conception’ of learning, which in his model is social in nature. In his view, it is this conception the one that really requires all our attention. From his perspective, then, the traditional format that has been used to promote learning, regardless of the specific conception of it, is not as productive as the meaningful transformations that individuals and groups of individuals experience when they actually learn. He believes that:

What does look promising are inventive ways of engaging students in meaningful practices, of providing access to resources that enhance their participation, of opening their horizons so they can put themselves on learning trajectories they can identify with, and of involving them in actions, discussions, and reflections that make a difference to the communities that they value.(p.10)

This excerpt summarizes in a nutshell the main assumptions behind our project. Although it is not for us to say it, we feel we provided an inventive way to engage a group of EFL preservice teachers in a social practice that was significant for them to the extent that they could access resources that would have probably remained untapped had we chosen a traditional lecture-like approach to the course.

When attempting to define his concept of ‘community of practice’ as a unitary notion, Wenger claims that “Because they belong to a community of practice where people help each other, it is more important to know how to give and receive help than to try to know everything yourself. (p.76)

The two quotations above also fit perfectly into the plan we made for the course we taught. Among other objectives, we wanted our students to engage in a type of learning environment in which the two different types of agents involved could share what they knew, did not hide what they lacked, and were willing to demonstrate that they were open to receive help. Thus, as the two educators in charge of the sections of the course –through our own didactic strategieswe presented and explained contents that were undoubtedly new to them. At the same time, through the help of two peers, our assistants, our students engaged in a task which demanded that they use the technological sophistications that characterize their generation. They were asked to construct, in the course of the semester, an academic blog that included both readings on topics previously presented in class by themselves and a format that allowed the interaction with both the teacher and their peers. The hypertexts used in the construction of these blogs combined on screen texts, images and hyperlinks to videos or documents that complemented or expanded on the concepts being discussed. Part of this material included their own PowerPoint presentations used to introduce the texts to the class. The main objective of this activity was to contribute to their own transformation of ‘outside knowledge’ into their own mental representations of that information through active cognitive engagement.

Throughout the term, the students formed what Wenger would call a ‘community of practice’.

...collective learning results in practices that reflect both the pursuit of our enterprises and the attendant social relations. These practices are thus the property of a kind of community created over time by the sustained pursuit of shared enterprise. It makes sense, therefore, to call these kinds of communities communities of practice. (p. 45)

The fact that their skills, in the use of both technology and the second language, were heterogeneous is not surprising and by no means does it invalidate Wenger’s conception of ‘community of practice’. Consequently, as they progressed in the construction of their blogs, we observed ‘engagement in action’, ‘interpersonal relations’, ‘shared knowledge’, and ‘negotiation of enterprises’, all of them features that Wenger considers important (p.85). Our original plan, which encouraged continuous interaction between Chilean and Colombian students, succeeded in its first phase by means of a videoconference and in the dialog that was carried out through their personal and debate blogs.

There is not a profound gap between Wenger’s theoretical stance on learning as social participation and the Vygostkyan sociocultural perspective, in spite of constituting different alternatives to account for the same processes. Although not exempt from criticism, sociocultural theory offers an interesting conception of learning to be summarized in the following section.

Sociocultural theory

Swain and Lapkin (1998, p.321, cited in Mitchel & Myles, 2004, p.193) contend that “the co-construction of linguistic knowledge in dialogue is language learning in progress”. This quote synthesizes the core assumption behind socio-cultural perspectives on second language learning. Interaction is not simply considered as an important part of the process conducive to language learning but constitutes the learning process in and of itself. In other words, the advocates of socio-cultural perspectives view learning in general and language learning in particular as being social first and only afterwards individual.

Yet, closely connected to our objectives of incorporating elements of criticality in this project, we need to add the influence that the work of Paulo Freire has had in developing a critical pedagogy for second language literacy. Freire and Macedo (1987), for example, emphasize the notion of ‘reading the word and the world’ by paying attention to the social contexts and social practice of literacy. As our students compared, for example, the status of teachers in both the Chilean and Colombian societies they were able to critique the power structures underlying the social roles, functions and status accorded to (language) teachers. As linguists and language teachers know well, throughout the history of our disciplines the conceptions of “language” and “learning” have changed and each new perspective has derived, inevitably, from the linguistic and the psychological positions that have been adopted at different points in time. As Brown (1994:5) explains, one of these views has defined language as being systematic and generative; another has focussed on the presence of prefabricated elements that also characterize it. At present we still face controversies with regard to an explanation of what language and language learning are. McCarthy (2001) presents an analytical synthesis of this controversy. On the one hand, the strictly psycholinguistic perspective claims that language is an abstract system of rules that the child, in his role as “little linguist”, is able to discover. Although psycholinguists do not neglect the role of the data or samples of language that the child is exposed to, their explanation of language learning highlights the process that occurs inside the child’s mind. In the context of second language learning, the assumption is the same. On the other hand, McCarthy continues, the sociolinguistic perspective overemphasizes the social function and purpose of language. If during first language acquisition the caretaker engages in social negotiation with the child by simplifying her speech and consequently allowing the co-construction of language, the language teacher’s role is supposed to replicate this constant process of meaning negotiation.

Although at first sight these two theoretical viewpoints seem to be mutually exclusive, we believe, like Susan Gass (in Seidlhofer, 2003) that they can complement each other relatively well. She states that:

Views of language that consider language as a social phenomenon and views of language that consider language to reside in the individual do not necessarily have to be incompatible. It may be the case that some parts of language are constructed socially, but that does not necessarily mean that we cannot investigate language as an abstract entity that resides in the individual. (p.227)

The interaction with the input through negotiation of meaning can be interpreted as a springboard for the activation of the child’s linguistic device and mental processes. And it is this interaction, now using technologies as computers and videoconferencing, the one we were interested in evaluating in this study.

Along with shifts in TEFL from teachercentered to learner-centered curricula came the realization that computer mediated communications (CMC) was also marking the transition of the teacher’s role from that of the “sage on the stage” to that of “guide on the side”, (Tella, 1996 cited in Warschauer, 1997, p.478). Even though trainees may come with sophisticated computer literacy skills (with the chip built in, so to say), the educator knows how to provide scaffolding activities for the community of interest to pick up. From a Vygotskyian perspective, the educator introduces the ´scientific´ concepts to complement and expand on the ´spontaneous´ concepts the learners bring with them. For Vygotsky, spontaneous concepts are developed through the child’s own mental efforts, whereas scientific concepts are influenced by adults. Scientific concepts differ from spontaneous concepts in two respects: firstly, they are distanced from immediate experience and thus allow for systematic generalizations and, secondly, they involve self-reflection (metacognition).

Mitchell and Myles (2004) explain that sociocultural theorists establish a difference between the apparently similar views represented by Vygotsky´s model based on the construct of ‘Zone of Proximal Development’ (ZPD) and Krashen´s ‘i+1 hypothesis’, which in turn is one of the five hypotheses that make up his well-known and controversial model known as the monitor model. Mitchell and Myles account for such difference saying that:

The Input Hypothesis prioritizes psycholinguistic processes, with linguistic input just ahead of the learner’s current developmental stage systematically affecting the learner’s underlying second language system. Application of the Zone of Proximal Development to SLL assumes that new language knowledge is jointly constructed through collaborative activity, which may or may not involve formal instruction and meta-talk, and is then appropriated by the learner, seen as an active agent in their own development. (p.200)

A misconception that we feel Mitchell and Myles try to clarify has to do with the difference between the advocates of Vygotskyan theory of SLL and the advocates of interactional models. It is common knowledge that Vygotskyan theoreticians are against “transmission” models of communication. What we sometimes ignore is that they also seem to criticize the perspective of interactionists. As Mitchell and Myles explain: They are also critical of input/interactional models in which ”negotiation of meaning” is central because they believe that this view fails to capture the main characteristics of language use which they say is to solve problems regardless of the speakers´ communicative intent.(p.206)

Although the socio-cultural perspective has been highly critical of other well-known linguistic models such as the Saussurean and the Chomskyan views, it has not been completely exempt from criticism itself. Mitchell and Myles put it this way: “However, socio-cultural theorists of SLL do not offer in its place any very thorough or detailed view of the nature of language as a system- a ‘property theory’ is lacking.” (p.220)

One possible solution to the presumed “artificial” character of foreign language learning interactions is to open up the contexts in which learners interact and include CMC where they are paying attention to the problems or tasks they have to deal with rather than to how grammatical or appropriate their use of the language can be. Even though we may here have the traditional tension between fluency and accuracy, in this project we also provided opportunities for them to use their “monitor”, as when our students had to present their in-progress reports and their final blogs to the class.

We are not necessarily making here a clearcut distinction between the position advocated by the interactionists and that of the Vygotskyan theorists but clarifying that the former is more focussed on negotiation of meaning and the latter on problem-solving interactions.

What we have done with our groups of foreign language learners at our universities in Chile and Colombia has been to stimulate the use of technology in a systematic and creative orchestration of the skills they are already supposed to bring with them in their capacity as “screen-agers” and the new information from applied linguistics they read about and complemented with their Internet searches. For the purposes of this course, we have understood applied linguistics as a discipline that takes care of language-related problems, concerning specifically the teaching and learning of second languages.

The collaborative work done succeeded in bringing together the expertise of a young generation and that of a much older one because, as Farías argues (2005): “Los grupos sociales se diferencian, como consecuencia, en aquellos que pertenecen a la generación de la pantalla (o post tipográfica) y aquellos que pertenecen al grupo tipográfico.” (p. 27)

Multimodal learning and hypertextualityAs applied linguists, we are interested in the potential links between multimodality and aspects of second language acquisition (a concept we are using as an umbrella term to include all kinds of language learning processes, naturalistic and artificial, foreign or tutored as well as truly second or untutored). However, we are aware of the fact that the interest in the area of multimodal learning is certainly much broader and covers practically all bodies of knowledge. As Kress and van Leeuwen (1996) explain:

We believe that visual communication is coming to be less and less the domain of specialists, and more and more crucial in the domains of public communication […] Not being ‘visually literate’ will begin to attract social sanctions. ‘Visual literacy’ will begin to be a matter of survival, especially in the workplace (p.3)

And it is here that our professional interest in multimodality makes a lot of sense. The application to second language acquisition of some of the principles already tested by psychologists in other disciplines may help us understand how exactly the different modes of presenting the information to the second language learner may facilitate (or hinder) the interaction needed.

In their work using a platform provided by the University of Dundee, in Scotland, our students´ engagement with different sources of information on topics related to applied linguistics evidenced in their practices the findings informed by Mayer and other psychologists. When Mayer makes reference to the so-called multimedia principle, he explains that “students learn better from words and pictures than from words alone.” (2001, p.63)

Our young teacher trainees were involved in diverse activities during the course of the semester. They read from printed material, they gave presentations whose topics were researched in different sources including the Internet, and worked on a final project which was constructed progressively and which illustrates quite well the application of this principle. Images and ‘words’ were always present in all of the blogs.

Even those of us who do not belong to the generation of ‘screen-agers’ or ‘digital natives’ know about the pervading impact of the writing technology known as hypertext that information and communications technologies have brought with them.

Cassany (2000) explains that for decades some writers have been able to develop hypertextuality in some literary genres- such as interactive novels for teenagers or experimental novels like Rayuela by Julio Cortázar. In turn, Vandendorpe (2003) when discussing the transition from linear to non-linear texts, mentions other literary texts that require nonlinear readings, like La vida, instrucciones de uso, by Perec, Pálido fuego, by Nabokov, and Crónica de una muerte anunciada, by García Márquez. However, all of today’s digital communication uses hypertexts as its basic structure. For a better understanding, especially on the part of ‘digital immigrants’ or older generations, Vandendorpe (2003) compares hypertexts with linear texts. Linear texts break down into several autonomous fragments that are connected with each other through links that allow the reader to rapidly jump from one to the others in any direction, like a spider through its web.

Hypertextuality was a key component and requisite of the academic blogs that our students had to create. Although they are used to reading in a non-linear fashion, having to look for material relevant to the issues discussed during the course and, then, organizing it using hypertexts was not always an easy task and most of them resorted to the knowledgeable scaffolding of our experienced assistants. Regardless of how difficult or relatively easy our students found their work with the platform, it is important to mention that in some of them there was an accurate perception of the ‘horizontal status’ of the interaction that could potentially take place. Thus, one of them stated that:

All of the countries that are linked to this website can expose their ideas about aspects concerning English language teaching. This platform, as well as the video conference, helps us to keep closer to the way other countries may think about everything regarding English learning and teaching. (S1)

This student is offering important evidence about another one of our objectives for this activity: that by using hypertextuality it was possible to raise our students´ rhetorical awareness both as text producers and text readers.

Part II Activities and analysis of the findings

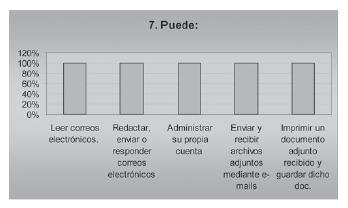

At the beginning of the semester, before negotiating with our students the instructions for the creation of their academic blogs, the Computer Literacy and Multimodality Questionnaire was administered (see Appendix 1). The objective of the questionnaire was to find out, before involving these students in our project, how computer literate they were about the information and communication technologies that make digital communication possible. It was not at all surprising to find out that they are familiar with the great majority of these technologies. Graph 1 below illustrates how knowledgeable they are in using reading and sending emails, administering their email accounts, sending and receiving attached files and printing and saving them.

At the end of the semester, we applied an open-answer survey containing a question about the use of the platform and another about the video conference. Some of the answers to this survey are used in this paper to illustrate the students’ reception of these activities.

The ‘ourdigitalculture.org’ platform.

Nick Hine has brought forward the idea of ‘critical pedagogy’ as a key concept for the “Our digital culture” project (www.ourdigitalculture. org), the platform we used during the course of applied linguistics.

In an interview held in July of 2008 at the University of Dundee, Scotland, Farías asked Nick Hine how the notion of ‘critical pedagogy’ was reflected in the work that he and his team are doing. We would like to quote part of his long response:

The critical pedagogy aspect is the single unifying concept that can associate the different curricula across, even within one city, the different cultures and the different situations around the world that we are working with….. So the notion of critical pedagogy applies in knowing society, knowing your place in society, being able to be critical of society in order to identify where change would take place.

For language education training, and in our particular experience as teachers of a course in applied linguistics, we introduced the learners into the discourse of the (scientific concepts of the) language teaching profession by having students read and reflect on issues in the fields of psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics, pragmatics and discourse studies.

We expected to create communities of interests with similar students in Colombia, but the lack of supervision and follow up of the exchanges ended up converting the platform work in a local forum and the activities became more of an exercise in incorporating scientific concepts in applied linguistics and building computer literacy skills.

The following list shows the instructions that our students were given for the construction of their academic blogs:

Instructions for the construction of academic blogs

- Use your own, creative “organization” (you can use sound, images –still pictures and/or animated pictures-color, etc.)

- Your blogs must obligatorily contain three elements: text + image + hyperlinks.

- The topic to be developed: the same topic (in more depth) you selected for your presentation

- Where will you get the information from? The Internet Your peers from Colombia The university libraries

- You must use hyperlinks which will take the reader to the information you have been able to collect.

Each hyperlink must contain a brief summary (a sort of statement that summarizes the information that each hyperlink takes us to) Include a “text” (your own text) in which you introduce and summarize the main ideas you have extracted through your readings, using your own words.

When Farías asks Hine: “In your opinion, what have been the main challenges that you have had, as an administrator of this platform?”, Hine refers to one that is not easy to solve, the fact that Chile, like the countries in the Southern hemisphere and unlike those in the Northern hemisphere, has a long break in the transition from one year to the next but a short break in the middle of the year. This means that when other countries are on vacation in July and August, Chile is busy. When Chile is on vacation in January and/or February, other countries are working. He explains: “…if there’s a lag in responding, then people lose faith in it.”

The obvious idea that the virtual community created through a virtual platform is constructed collaboratively by its users is clearly expressed by one of the students:

…if the platform has no active users, there is no point in using it and having it there. We cannot force anybody to go online and try to interact with others if the person doesn´t want to. Learning and critical thinking can be achieved by other means and we should never forget that. (S2)

Structural problems dealing with access to ICTs and connectivity confabulated against the success of the original objectives for this project; yet, it offers an interesting diagnosis of the problems encountered when applying in communities in the Periphery models imported from more resourceful contexts in the Center (we are using the concepts of Periphery and Center following Kachru’s model).

Concretely speaking, most of the students at state universities in Chile come from socioeconomic backgrounds where computers are not still part of the household items. Thus, these students log on from cybercafés, internet shops or from computers at the university libraries.

At any rate, and despite problems of connectivity, the fact that the new generations, as Rueda and Quintana (2007) would put it “come with the chip built in” and can be critical of certain designs in CMC, can be illustrated by the following assertion by one of the students that participated in this project: “Maybe the page, I mean its design, is not appealing to us, or maybe we feel not attracted to virtual communities because it is something we have been dealing with for many years; it does not impress us”.

Moreover, we can appreciate that some of them have already developed what has been called ´critical multimodal literacy´. For example, one of the students, after reading some texts on multimodality (scientific concepts) was able to come up with a critical appraisal of the platform:

The main problem is its design because of the lack of certain elements that make social networks attractive to people (use of video, graphics, photo galleries, profiles, messenger system). In the perspective of “multimodal learning” this is fundamental because well-designed platforms encourage cognitive processing and make possible exchanges of ideas among learners and teachers. In other words, text-based platforms could not make these processes possible.(S3)

Interestingly, when applied to develop computer literacy skills, which was indirectly one of the objectives of this experience, Buckingham (2003) postulates that “media education might be seen to provide a body of scientific concepts which will enable them(students) to think and to use language (including ´media language´), in a much more conscious and deliberate way”. (p. 141).

With respect to our objective of raising the students´ rhetorical awareness both as text producers and text readers, we can mention:

a. The problems the students underwent in the construction of their blogs with the use of the platform’s tools. As teachers and attempting to scaffold an activity that was beyond our own capacities, we selected two assistants whom we have known from previous courses to possess high computer literacy skills. These two assistants in little time designed a tutorial for blog construction that helped most students to create and upload their blogs.

b. Faced with such problems with the platform´s tools, some students decided to migrate to more familiar and user-friendly grounds and so built their blogs using blogspot.

c. Through the process of blog construction, novice teachers were able to notice such problems as paraphrasing to avoid literal cut and paste composing, concordancing to accommodate referenced texts in person, number and gender, and text organizing to edit multimodal discourses where videos, texts and sound files were included.

Thematic discussions in the debate blog and videoconference

The videoconference (VC) was an activity designed to launch the collaboration between the Chilean and Colombian students. It might be worthwhile mentioning here the importance of interdisciplinary dialog among university educators as we could not have had the VC without the support from a colleague researcher in the VirtualLab project at USACH who dealt with the technicalities of the connection and provided the room for the vc to take place. One of the main topics addressed was the comparison between the two educational systems in terms of quality standards differentiating public an private schools.

We hadn´t much time to discuss the main topic (public education in both countries), but I think we all agree that since we are inserted in a latinamerican context, we share many of the problems discussed. (e.g. number of students per class). Same as with the platform, in this experience we can learn through other students´experiences and we can get deeper comprehension when things are presented in a “conversational style rather than a formal style.(S4)

This student is expressing, among other things, her support towards one of the phenomena investigated and tested by Mayer and that the students had to read about as part of the course syllabus. She is making reference to Mayer´s (2001) ‘personalization effect’ which states the following:

Multimedia messages result in better trans-fer performance (but not retention) when the verbal material is presented in a conversational style-using first and second person – than when the identical verbal material is presented in a nonconversational style – using third person.(p.188)

Another trainee found that through videoconferences some cross curricular values can be promoted:

A videoconference also helps us to develop tolerance and respect for that person who is sharing his/her opinion. One of the most important problems that I can mention here are the frequent loss of the signal with Colombia (video and audio), and the difficulties (technical ones) in understanding what the Colombian students were trying to say. (S5) This encounter with culturally different others (Todorov) is an essential learning activity as out of the comparison comes the realization of identical problems and, what is more educationally interesting, the possibility of action (praxis, in Freire’s terms), as mentioned by the following students:

It was useful for me to find out that the Colombian reality is very similar to our Chilean educational reality……I realized that education is a global problem that can be solved, first of all, by sharing experiences, and then, trying to find out solutions to the problems in collaboration. (S6)

In Colombia, people who decide to be teachers really have the vocation because economically they won´t receive a lot of money. (S7)

For some students the two activities were complementary in that one promoted the active production of the second language, which is not something that all the students find easy, whereas the other encouraged a different kind of active agency. When elaborating their hypertexts the learners can still learn by ‘experiencing’ the new knowledge through the search for adequate material on the selected topics; however, this type of engagement does not cause them the type of anxiety (language learning anxiety, communication apprehension, foreign language classroom anxiety, see Horwitz and Young 1991) that oral production in front of an audience usually provokes.

I found myself very motivated to listen and understand the Colombian students´points of view about the topic we were talking about. However, I did not participate talking or giving my opinion because as many other students I think, I prefer to express myself through the use of the platform, which gives me more confidence and I don´t feel that kind of “panic” that most people feel when talking in public. (S8)

One of the benefits that some students could observe in the interaction through a videoconference was the realization that at least two of the countries in the same continent face the same problems that they have already perceived as young novice teachers of English.

The interaction is always positive and enriching. In this videoconference we all were aware of the similarities between our colleagues´problems in Colombia and ours. As two cultures have diverse influences and characteristics we can share our experiences on how to face and deal with these problems.

I think there´s a great deal of what is mentioned on pages 187 and 188 about speakers as virtual communities. Discussing a topic related to education between the same groups of people is certainly quite different from discussing a topic related to education with a multimedia tool as videoconference. Because we had the chance to exchange experiences, ideas and realities. We could see what we have in common and not. (S9)

Students´ engagement in the forum and in the debate blogs show how dialog and learning communities, sharing ideas and opinions helps their process of becoming teachers.

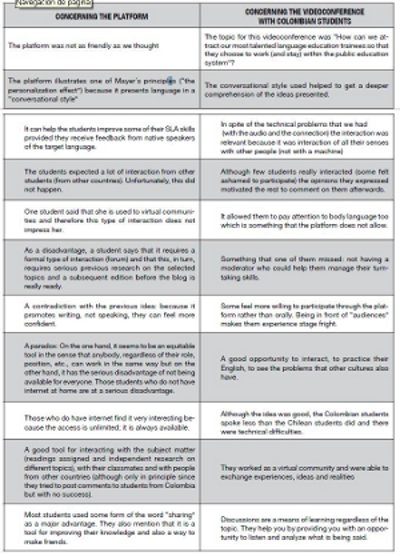

Students´ opinions on the two activities with ICTs: synthesis.

Table 2 shows a synthesis of the opinions from the Chilean novice teachers after their experience working on the platform and the videoconference held with their Colombian peers:

Conclusions

We here need to confess that the two authors of this paper were really impressed by the final projects our students produced in their blogs they created through the platform. Rather than an impression that may bring frustration to see such sophisticated computer literacy in our students (that we are slowly learning), these projects provide great avenues to engage second language learners in activities that explore the potentials of CMC for critical thinking.

At the same time, the diversity in styles, learning paces and criticality, demonstrated the democratic nature that lies at the heart of every community of interest and practice: the respect for individual differences while doing collaborative work.

Language teacher education needs to provide novice teachers with skills, attitudes and design elements for them to orchestrate in the best possible way, activities aimed at deploying their future students’ creativity and critical thinking skills. As teachers, we must begin to include these interactions with technology in our repertoire of activities while considering the new literacies needed to construct and share personal interpretations within Internet communities.

The (already) buzz words of ‘communities of interest’ and ‘practice’ have brought our attention, once again, to the human potential to learn by collaborating in the construction of empowering projects. If this is not one central aim of education, we are out of here.

Acknowledgments

The elaboration of this article was possible by support from DICYT USACH, Project 03065FF.

References

Brown, D. (1994). Principles of language learning and teaching. New Jersey: Prentice Hall Regents.

Buckingham, (2003). D. Media education. Literacy, learning and contemporary culture. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Cassany, D. (2000) De lo Analógico a lo digital: El futuro de la enseñanza de la composición. Revista Latinoamericana de Lectura, junio, n.2, p.1-11.

Farias, M. (2005). Multimodalidad, Lenguaje y Aprendizajes, Contribuciones Científicas y Tecnológicas, Usach, No 133, 33, p.26-31, Available also at http:// www.usach.cl/VRID/pub

Farias, M. (2008). (unpublised paper). Farias interviews Dr. Nick Hine at the University of Dundee, Scotland. June.

Freire, P. and D. Macedo. (1987). Literacy: reading the word and reading in the world. South Hadley, MA: Bergin and Garvey.

Kress, G. y T. van Leeuwen. (1996). Reading images. The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.

Horwitz, E and D. Young (eds). (1991). Language Anxiety. From theory and research to classroom implications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Mayer, R. (2001). Multimedia Learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

McCarthy, M. (2001). Issues in Applied Linguistics, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mitchell, R. and F. Myles. (2004). Second Language Learning Theories, New York: Oxford University Press.

Quintana, A. and R. Rueda. (2007). Ellos vienen con el chip incorporado. Bogotá: Universidad Distrital FJDC.

Seidlhofer, B. (2003). Controversies in Applied Linguistics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Vandenhorpe, C. (2003). Del papiro al hipertexto. México, DF: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Warschauer, M. (1997). Computer mediated collaborative learning: Theory and practice. The Modern Language Journal, vol. 81, No 4, (Winter, 1997), pp. 470-481.

Wenger, E. (2007). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

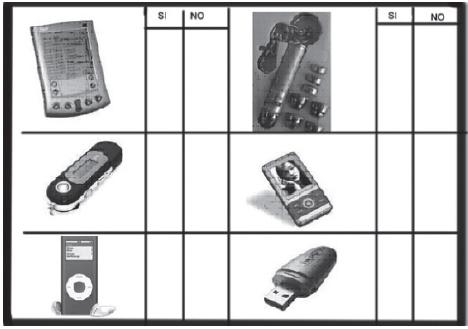

APPENDIX 1: Cuestionario de Alfabetización Computacional y Multimodalidad.

UNIVERSIDAD DE SANTIAGO DE CHILE DEPARTAMENTO DE LINGÜÍSTICA Y LITERATURA

Grupo de Investigación acerca de la Multimodalidad y la Enseñanza del Idioma Inglés

Multimodality and English Language Teaching Research Group (MELTG)

Cuestionario de Alfabetización Computacional y Multimodalidad.

Nombre : _____________________________

Apellidos: _____________________________

E - mail: _____________________________

Instrucciones: El cuestionario se debe responder siguiendo las instrucciones que se especifican en cada sección del cuestionario.

Favor conteste de forma veraz TODAS las preguntas.

Para aquellas preguntas que requieran desarrollo, escriba la respuesta en el espacio destinado para ello.

Operaciones Computacionales y Conceptos básicos.

1. Escriba el nombre de las figuras que se muestran asociadas al computador.

2. Puede …? Marque con una “X” las afirmaciones que representen lo que Ud. es capaz de hacer computacionalmente.

- Crear archivos

- Guardar información en los archivos

- Acceder a la información guardada en los archivos

- Cerrar correctamente una aplicación (ej: ventana, programa, etc)

- Apagar un computador apropiadamente

Habilidades para procesar texto

3. Puede..? Marque con una “X” las afirmaciones que representen lo que Ud. es capaz de hacer en un documento.

- Crear y guardar un nuevo documento tipeado

- Cortar, copiar y pegar un texto

- Cambiar el tipo y tamaño de letra

- Justificar un texto y cambiar el espaciado

- Fijar los márgenes de un texto y seleccionar su orientación (vertical/horizontal) en un programa procesador de texto

- Incluir números de página y encabezados/notas al pie

- Enumerar o destacar una lista

- Crear tablas

- Crear formas

- Insertar hipervínculos

- Insertar elementos multimedia (gráficos, imágenes, recortes de otro documento)

Habilidades para la Internet/Redes (Web)

4. Puede..? Marque con una “X” las afirmaciones que representen lo que Ud. es capaz de hacer.

- Acceder a un sitio web especifico dada su dirección URL (Universal Resource Locator).

- Crear páginas web simples

- Usar un buscador web

- Seguir hipervínculos

- Guardar la dirección URL de un sitio Web para visitarla más tarde (“marcadores” “favoritos”)

- Usar un motor de búsqueda Internet (ej. Yahoo, Google, Infoseek) para encontrar información específica

- Descargar y guardar archivos desde la Web (ej. textos, graficos, archivos PDF)

- Descargar e instalar programas de lectura (browser plugins) tales como Acrobat Reader y Real Audio

Multimedia

Marque con una “X” las afirmaciones que representen lo que Ud. es capaz de hacer.

5. Puede…?

- Usar presentaciones Power Point

- Insertar gráficos e imágenes en su archivo Power Point

- Subir/descargar archivos hacia/desde sitios web gratuitos

- Chatear en una sala de chat (ej. MSN, Skype)

6. Sabe Ud. usar los siguientes artefactos electrónicos?

Correo Electrónico (E-mail )

Marque con una “X” las afirmaciones que representen lo que Ud. es capaz de hacer.

7. Puede…?

- Leer correos electrónicos

- Redactar, enviar o responder correos electrónicos

- Administrar su propia cuenta de correo electrónico (copiar, guardar, reenviar y borrar mensajes).

- Enviar y recibir archivos adjuntos mediante mensajes de correo

- Imprimir un documento adjunto recibido a través de un correo electrónico y guardar dicho documento en un lugar

- apropiado (ej. Carpeta Mis Documentos)

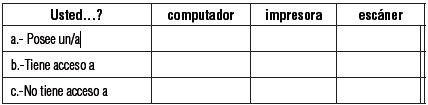

- Acceso a computador, impresora y escáner

8. Marque con una “X” en la siguiente tabla, contestando las alternativas que correspondan de acuerdo a su caso.

Implementos de su computador (Hardware).

9. ¿Qué tipo de computador tiene?

____________________________________________________

10. ¿Cuál es el sistema operativo que su computador tiene?

____________________________________________________

11. ¿Cómo se conecta a Internet?

- Network

- ADSL

- Modem (acceso telefónico)

- Tecnología Inalámbrica (Wi-fi)

- No tengo acceso aInternet.

12. ¿Tiene experiencia en diseño de páginas web?

Si No Algo

Sección de Multimodalidad

1. Conoce el significado de la palabra Multimodalidad?

Sí No

2. Conoces la diferencia entre Multimodalidad y multimedia

Sí No

Si la respuesta es sí, explícalo en tus propias palabras.

Multimodalidad es: ___________________________________________________

Multimedia es: ________________________________________________________

3. ¿Estás consciente del uso de la Multimodalidad en el proceso de aprendizaje del Inglés?

Questionnaire adapted by A. Góngora, B. Rivera and D. Veas from EDFS 326/687 Literacy Questionnaire, from the College of Charleston on line materials, 2006. Section on multimodality, prepared by R. Orrego.

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.