DOI:

https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.185Published:

2003-01-01Issue:

No. 5 (2003)Section:

Research ArticlesTeachers’ informed decision-making in evaluation: Corollary of ELT curriculum as a human lived experience

Keywords:

ELT curriculum, evaluation approaches, teachers’ decision-making, technical evaluation, human evaluation, evaluation framework, small-scale evaluation projects. (en).Downloads

References

Brown, J.D. (1995). The elements of language curriculum: a systematic approach to program development. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Brown, J.D. (1996). Testing in language programs. New Jersey: Prentice Hall Regents.

Clavijo, A. (2001). Redifining the role of language in the curriculum: Inquirybased curriculum an alternative. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal,

,1.

Genesee, F. and Upshur, J.A. (1999). Classroom-based evaluation in second

How to Cite

APA

ACM

ACS

ABNT

Chicago

Harvard

IEEE

MLA

Turabian

Vancouver

Download Citation

Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 2003-09-00 vol:5 nro:5 pág:122-138

Teachers' informed decision-making in evaluation: Corollary of ELT curriculum as a human lived experience

Álvaro Hernán Quintero Polo

is an assistant professor in the undergraduate and graduate language programs at Distrital University in Bogotá, Colombia.

lherquin@hotmail.com

ABSTRACT

This article characterizes informed decision-making as one important activity of evaluation in the English Language Teaching (ELT) curriculum. I emphasize on a distinction between human and technical approaches to evaluation. This emphasis is consequence of my reflection upon my and some in-service teachers' perceptions about literature and small-scale research projects related to the area of evaluation. In this article, I also intend to contribute to an understanding of why educational processes need to be seen as a lived experience for which informed decision-making can be used as a sound practice in a process of evaluation. A practical academic experience illustrates the discussions in this article. I led the practical experience as a professor of a seminar on testing and evaluation in English language teaching (ELT), in the Master's Program in Applied Linguistics to the Teaching of English as a Foreign Language at the Distrital University in Bogotá, Colombia.

RESUMEN

Este artículo examina la toma de decisiones ilustrada como una actividad importante de la evaluación en el currículo de la enseñanza del idioma inglés. El énfasis aquí es en la distinción entre dos enfoques para evaluar: uno humano y otro técnico. Este énfasis resulta de mi reflexión sobre lo que algunos docentes y yo percibimos acerca de la literatura y unos proyectos de investigación a pequeñescala relacionados con el área de evaluación. Intento además contribuir al entendimiento de por qué los procesos educativos necesitan ser vistos como una experiencia vivida para que la toma de decisiones ilustrada pueda usarse como un ejercicio evaluativo válido. Una experiencia académica práctica sustenta las discusiones en este artículo. Conduje esta práctica como profesor de un seminario sobre evaluación en la enseñanza del inglés. Este seminario hace parte del Programa de Maestría en Lingüística Aplicada de la Universidad Distrital en Bogotá, Colombia.

KEY WORDS

ELT curriculum, evaluation approaches, teachers' decision-making, technical evaluation, human evaluation, evaluation framework, small-scale evaluation projects.

INTRODUCTION

Before starting to read this article, I invite you to recall situations in which you had to make any sort of decision in the last couple of hours. Now, let me guide you in a brief retrospective practice through some questions: Would you say that you made not only one but many decisions? If you did make some decisions, you may agree with me on the idea that decision-making is a daily mental activity every human being carries out. Provided that you made some decisions, could you account for the consequences of those decisions? You will probably think that as humans, we might be either right or wrong after we decide something. Finally, what were the foundations of your decisions? You may perhaps say that your decisions were based upon experiences, beliefs, academic training, or merely common sense. Nevertheless, the tendency to rely only on intuition may lead to making mistakes. Minimizing risks, thus, becomes mandatory.

After this short retrospection, I could perhaps introduce the issue of decision-making as a significant aspect of evaluation in school life. As teachers, we have to make decisions, too. This requires a less informal perspective, a curriculum perspective. Evaluation is a curriculum activity that needs to be less casual and more systematic, less trivial and more critical, less technical and more human and emerges as a way to generate informed decisions.

In view of that, a characterization of decision-making as a significant aspect of evaluation is what I put forward in this article. This characterization is the result of my reflections upon my participation in an academic experience as a professor of a seminar on testing and evaluation in English language teaching (ELT), in the Master's Program in Applied Linguistics to the Teaching of English as a Foreign Language at the Distrital University in Bogotá, Colombia. This reflection has my appreciation of some related literature as a complement and support. Furthermore, I must mention that some in-service teachers who were also participants in the seminar provided me with insights through their perceptions about theories and practical small-scale research projects related to evaluation. The manner I organize this article is as follows: Firstly, I describe a practical experience that includes the seminar on testing and evaluation in ELT and the small-scale research projects. Secondly, I discuss a theoretical component that connects curriculum, evaluation, and decision-making as key terms. Thirdly, I examine the participants' perceptions about the practical experience and theories. Finally, I draw some conclusions.

PRACTICAL EXPERIENCE

As a professor, I usually find out that issues of evaluation inspire curiosity and concern among professionals in ELT. For instance, for some, measurement is a challenging puzzle or problem they want to solve, others wonder how they can do a better job in determining what learners know and can do. Furthermore, an effort to inform certain decisions about pedagogical interventions and an attempt to become informed about the potential misuse and abuse of testing and assessment results are points for discussion as well. In accordance with these ideas, what follows is a description of this experience in terms of the seminar on testing and evaluation in ELT and small-scale projects.

SEMINAR ON TESTING AND EVALUATION IN ELT

This seminar has made part of the structure of a master's program in applied linguistics to the teaching of English as a foreign language for at least the last three years. It has always been conceived as an opportunity for its participants to reflect upon their beliefs and practices regarding evaluation. The participants in this seminar have been mostly in-service language teachers who work in private as well as public institutions in Bogotá, Colombia. These teachers have taught for some years at various levels such as, primary, secondary, and university. Moreover, the seminar has included, among others, activities to examine monitoring procedures of the English teaching/learning in the participants' contexts, instruments used for measurement, how they are used and the reasons for their use. In sum, the seminar has been based upon the participants' critical reflection and practical experiences.

The reflective and critical approach of the seminar has made the participants explore ways to move from purely technical knowledge development to an experiential approach that considers the human dimension of evaluation as a significant activity of a curriculum. As part of this, informed decision-making has also been understood as a curriculum activity.

The objectives of the seminar have contemplated the development of critical knowledge and competencies in evaluation as a means to monitor not only a course of study or plan, but also school life and educational experiences. Moreover, the participants have discussed how and why the instruments for assessment are used in their contexts. These objectives have been confronted with exploration of theories. In general, the participants have been expected to develop an individual approach to testing, assessment, and evaluation.

The content of the seminar has been divided into three modules: evaluation, testing and assessment. The modules have always emphasized on evaluation as an ongoing informative activity of the ELT curriculum. Among the topics for discussion and reflection in the seminar, there are the following: Curriculum components and activities, general principles of evaluation, framework for evaluation in ELT, evaluation in ELT projects, planning and conducting evaluation, testing principles, critical perspectives on tests, testing and research of English as a foreign/second language, test types and features, test procedures and techniques, assessing foreign/second language proficiency, formal and informal assessment, literacy assessment. These topics have been dealt with by authors of articles selected for the seminar reading assignments.

A balance between theory and practice has characterized the methodology of this seminar. This has been done by means of illustrated lectures, weekly reading assignments, workshops about practical evaluation tasks, and plenary discussions. The lectures are presentations about topics included in the syllabus. These lectures have been taken as the guidelines for the practical applications and plenary discussions. As for the weekly assignments, the participants have prepared brief oral reports of their personal insights based on readings included in the syllabus and practical experience. There have also been workshops in which the participants have found application of the theoretical and practical discussions to their regular professional activities as part of an in-service training.

The reflective component of the seminar has been the participants' contribution to the development of experiential knowledge on evaluation since have stated their perceptions about testing, assessment and evaluation and they have related those perceptions to their experiences in teaching and research. This leads me to refer to the research component of the seminar that has taken the form of small-scale projects in which participants have integrated theory and practice related to the general area of evaluation in ELT. This last component is better described below under the subheading small-scale projects. I will address both the theoretical and reflective components afterwards in the sections titled theoretical component and participants' perceptions.

SMALL-SCALE PROJECTS

The small-scale projects have been practical research activities whose main objective has been to integrate basic research elements, theoretical knowledge, professional experience, academic competencies, and reflections upon English language teaching adopting a perspective from the ELT curriculum. The participants have had the opportunity to demonstrate, among other abilities, those of evaluating personal and professional experiences, awareness of their participation as agents of change and innovation, creativity to solve difficult situations, and reflection upon their own academic competencies. This is related to the regulations of Colombian public education (Ley 115) that refers to the need for teachers to think of their roles as innovative and well-informed educators.

The participants have developed their projects in one semester. The minorscale research design has contemplated preparation, execution, and a written and oral report in the same semester. This has been accomplished in three stages. First, there is a statement of a proposal based upon data collection, exploration of theory-based and research-based articles, a rationale, an objective, a plan of activities, and some methodological aspects. Then, there is the implementation and monitoring of the proposals, data collection, and partial analysis. Finally, there is a final analysis and presentation of results together with some recommendations and implications for evaluation in teaching of English as a foreign/second language.

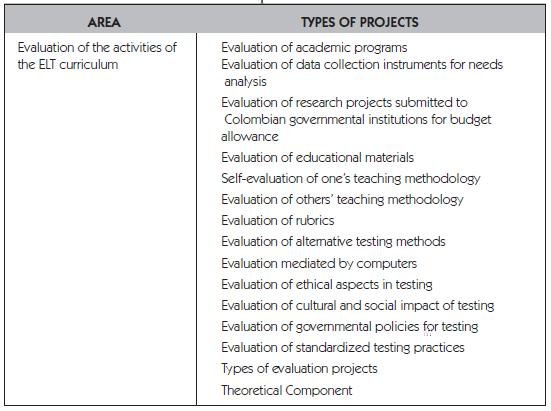

As seen in the chart below, the types of projects that the participants have chosen to develop are closely related to evaluation of activities of an ELT curriculum, as the main concern of the seminar.

Evaluation is an experience that has relevance for particular students and particular teachers in a particular context. Therefore, evaluation is an essential activity of the ELT curriculum and it is understood as a lived experience in school life (Simons, 1998). Teachers are closer to understanding the formal and informal students' curriculum experiences and how to access them. Since

many of the creative opportunities for learning take place in unexpected ways and at unexpected times, teachers and students are in a better position, than external evaluators, to document and evaluate the rich experience of learning. Therefore, those closer to the setting have a more immediate understanding and intimate knowledge of students. Simons, (1998) maintains that this evaluative perspective is what makes a difference ";(1) to how the issues for evaluation are conceptualized (frequently generated from observations in practice); (2) to the analysis, where outcomes can be related to specific processes and particular students; and (3) to the implications to be drawn for further curriculum development in the specific context" (p. 367).

This view of curriculum not as a course of study or a plan (technical approach), but as what actually happens to the students (human approach) is based upon classroom life itself and its influence on evaluation, becoming both means and ends simultaneously. To complement this idea, Clavijo (2001) states that ´curriculum organization and development represents a way of thinking and acting in school by teachers and students. Their active roles influence their decision about how to construct curriculum¡ (p. 34).

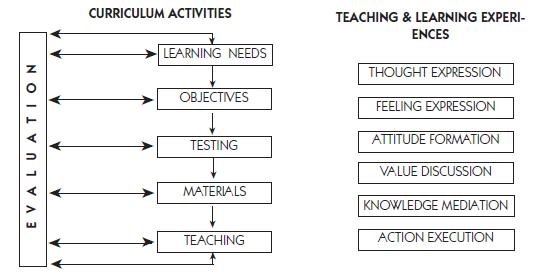

The technical approach to evaluation is remote, based upon prespecified and desirable goals. Conversely, as illustrated in figure 1 above, the human approach to evaluation in the ELT curriculum is continuous, immediate, based on classroom life, free from prespecified goals. Evaluation gives meaning, validity, and reliability to the curriculum because it can determine the effectiveness

of any of its components: learning needs, objectives, testing, materials, and teaching (Brown, 1995). Furthermore, it considers the teaching and learning experiences as the array of thoughts, feelings, attitudes, values, knowledge, and actions that teachers and students undergo and undertake in living their lives in schools. In this sense, evaluating the curriculum is not much different from evaluating living in general.

In the introduction of this article, I already mentioned that human acts involve evaluation of alternatives and consequently decision-making. Additional to that, in education teachers need to see evaluation as an experiential process which is serious, formal, systematic, and as an intrinsic part of teaching and learning (Rea-Dickins and Germaine, 1992); that is, an exercise upon learning events that requires from teachers ongoing evaluative tasks. More specifically, evaluation in the ELT curriculum needs to be more than an end-of-a-process activity. Complementary to this, Pineda (2001) proposes a compelling distinction between instructional evaluation and curriculum evaluation. Citing the Council of Europe (1996), she maintains that besides students' language proficiency, there is more to look at in the curriculum. Pineda believes (based upon Oliva, 1997) that curriculum evaluation marks the end of a cycle and the beginning of a new one. Since evaluation is related to decision-making, all information gathered in a cycle (including information from instructional evaluation) should be used to adjust the curriculum. Furthermore, Pineda suggests a principled evaluation of an English as a Foreign Language curriculum that accounts for both the development and outcomes as related to educational goals.

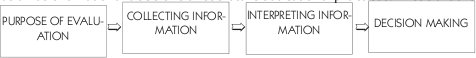

Classroom-based evaluation constitutes a major activity of the ELT curriculum. In this sense, Genesee and Upshur (1999) propose four stages that constitute a framework (figure 2) for evaluators to add a purposeful and interpretative component to their practice. Information becomes meaningful when it is interpreted, and meaningful interpretations are needed in order to decide what actions to take or what changes to make instead of moving straight from information collection to decision-making. Therefore, decision-making needs to be the result of a meaningful process that considers purpose, information collection, information interpretation in that very order.

Evaluation as a complex activity implies a process of gathering information in order to make good decisions, and includes both subjective input (opinion) and objective input (fact) through different forms that include assessment, testing,and self-reflection (Richards and Lockhart, 1994). Well-planned and wellcon-ducted evaluation provides useful information to show the real worth of an ELT curriculum, to show where to improve future teaching and learning practices, and as a basis for rational decisions about future educational practices. These are the

FIGURE 2. Classroom-based evaluation (based upon Genesee & Upshur, 1999)

formal and the systematic specifications of evaluation which are corroborated by Brown (1995) when he states that evaluation is "...the systematic collection and analysis of all relevant information necessary to promote the improvement of a curriculum and assess its effectiveness within the context of the particular institutions involved" (p. 24).

Additionally, the systematic dimension of evaluation requires from teachers appropriate use of instruments and procedures to gather data for curriculum development. From my point of view, in this process it is not enough to define the data collection instruments, it is also necessary to determine procedures, participants, purposes, goals and specific circumstances under which the evaluation process can take place effectively. This goes along with the statement by Heaton (1998) about explaining and confirming existing procedures and gaining information in order to bring about some change and innovation as the two main reasons to conduct evaluation in the ELT curriculum.

PARTICIPANTS' PERCEPTIONS

As one of the activities of the seminar, the participants have discussed their beliefs about testing, assessment and evaluation in ELT. These beliefs have been about theories and the participants' practical experiences. Moreover, the participants have expressed these beliefs orally or in writing. Their written expressions have taken place when they complete questionnaires or checklists, and report on their small-scale research projects. The participants' oral expressions of their beliefs have taken place in plenary discussions and presentations of their assignments of the seminar. To illustrate this section, I would like to mention only some points resulting from my analysis of the participants' written voices.

Using instruments such as the ones in the annexes (contributed by Dr. Austin, T. from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst) has been a usual practice of the seminar. Through them, the participants have had the opportunity to reflect, raise awareness, and discuss about topics that make up the contents of the seminar. For instance, I have perceived the participants' answers to questionnaire in annex one as a sign of a need to have an induction to different issues (other than tests) related to evaluation in an ELT curriculum as an initial stage of the seminar. With very few exceptions, the participants have initially declared having heard of topics included in the questionnaire but being able to neither define nor apply them to specific situations, or recognizing those issues only in the theoretical references. It has been interesting to see that in the initial stage of the seminar, the majority of the participants have not focused on testing as the only main topic of the seminar. There has been a tendency to consider a broader perspective to evaluation that relates the theory reviewed in the literature and the practice experienced by the participants.

As a wrap-up practice of the seminar, the checklist in annex two has provided the participants with insights about the understanding that they have gained because of the seminar. What has been noticeable in many occasions is that the participants have considered the concept of "true ability" as important when constructing instruments that elicit students' best performance. Furthermore, evaluation as a periodical, ongoing practice of an ELT curriculum has become a valid conceptualization that surpasses the image of evaluation as a questionnaire to fill out at the end of a program. The participants have also manifested that evaluation cannot occur in isolation from curriculum improvement. To be precise, the process of gathering useful information (including both opinions as well as facts) has been seen as necessary to determine where to improve teaching and learning practices, to make rational decisions about educational practices, and in general, to show the real worth of an ELT curriculum.

Regarding the small-scale projects reports, a common characterization of an effective evaluation resulting from this activity developed in the seminar has been as follows: evaluation means collecting, organizing, analyzing, and reporting data about a number of features of an ELT curriculum and its impact on its actors for decision purposes. The following sample of the pedagogical implications section in one participant's written report evidences this idea:

The projects have also shaped an outline of procedures to plan effective evaluation (based upon Genesee and Upshur, 1999): (1) during a program where techniques are used to change it while it is being developed and conducted (called formative evaluation), (2) at the end of a program or at the end of a specific part of a program where techniques are used to assess how well participants and the program meet the goals at the end of the instruction time (called summative evaluation), and (3) at some point or points after a program to assess the lasting effects of instruction (called follow-up evaluation). One participant, reporting on the methodology of her small-scale project writes:

"To develop this evaluation project I gathered information in three moments: before implementing a change, while the change was taking place, and after the change has been produced."

Consequently, effective evaluation cannot just happen on its own. The participants have manifested their agreement with the idea of evaluation as a carefully planned curriculum activity that provides them with useful information for their management and change of English teaching and learning tasks, planning of courses, and classroom practice. In the conclusion section of her written project report, one participant states that:

"Since a great part of our professional work has to do with decision making, at classroom level or at institution level, our role as informed teachers is to promote change towards evaluation in our institutions."

Finally, a common agreement that I have been able to identify in these project reports has been an identification of at least four areas that teachers can consider to decide on different components of the curriculum (based upon Tribble, 2000). These areas are as follows: (1) Planning the domain (topics, overall content) of the curriculum, the major goals, and the more detailed objectives; (2) programming (or setting up the logistics) the procedures for running the curriculum, facilities and other resources needed; (3) conducting the activities that make up the curriculum; and (4) deciding when and why to continue, evaluate, change, or end the activities that make up the curriculum. In connection with curriculum development, the key to planning a useful evaluation might be the same as the key to planning successful curricula (Tribble, 2000). For instance, a system for evaluating the curriculum must be put in place before a program begins. Allocation of adequate resources (people, time, materials) to plan and carry out the evaluation is a sensible strategy.

CONCLUSION

This article is a discussion that serves as an attempt to revise our conceptualization of evaluation as an activity of an ELT curriculum. I suggest a conceptualization of evaluation as an activity that is not different from evaluating living in general. My viewpoints here propose a more human and less technical approach to evaluation. If this approach is adopted in plans, teachers will be able to implement evaluation procedures as significant factors for those who want to embark on new programs or evaluate current ones in a formal and systematic manner.

The conceptualization that needs to be rethought is that of a technical evaluation that considers pre-specified, desirable, and remote goals. Conversely, I put forward the adoption of a human approach to evaluation that is continuous, immediate, based on classroom life that gives meaning and to an ELT curriculum. Furthermore, this human approach considers the teaching and learning experiences as the array of thoughts, feelings, attitudes, values, knowledge, and actions that teachers and students undergo and undertake in living their lives in schools.

The academic experience reported here has contributed to its participants' understanding of why educational processes need to be evaluated and to the consideration of informed decision-making as a sound practice. Decision-making needs to be the result of a meaningful process that considers purpose, information collection, and information interpretation. This process provides our beliefs and common sense with foundations to make decisions.

REFERENCES

- Brown, J.D. (1995). The elements of language curriculum: a systematic approach to program development. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

- Brown, J.D. (1996). Testing in language programs. New Jersey: Prentice Hall Regents.

- Clavijo, A. (2001). Redifining the role of language in the curriculum: Inquiry-based curriculum an alternative. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 3,1.

- Genesee, F. and Upshur, J.A. (1999). Classroom-based evaluation in second language education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Heaton, J.B. (1998). Classroom testing. Essex: Longman.

- Ministerio de Educaión Nacional. (1991). Ley general de la educación. Bogotá.

- Pineda, C. (2001). Developing an English as a foreign language curriculum: The need for an articulated framework. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 3,1.

- Rea-Dikins, P. and Germaine, K. (1992). Evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Richards, J.C. and Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflecting teaching in second language classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Simons, H. (1998). Developing curriculum through school self-evaluation. In Beyer, L. E. and Apple, M.W. (Eds.), The curriculum: problems, politics, and possibilities (pp. 358-379). Albany: The State University of New York Press.

- Tribble, C. (2000). Designing evaluation into educational change processes. ELT Journal, 54, 4.

- Willis, G. (1998). The human problems and possibilities of curriculum evaluation. In Beyer, L. E. and Apple, M.W. (Eds.), The curriculum: problems, politics, and possibilities (pp. 339-357). Albany: The State University of New York Press.

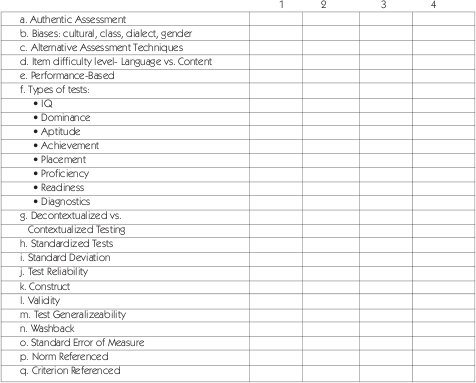

NAME: DATE:

Indicate your familiarity with the following concepts. Your answers will be used to help me determine class activities and set the pace of the course.

1. I can define it and apply it to a test. 2. I have heard of this concept, but would not be able to recognize it. 3. I know it when I see it. 4. I have never heard of this before.

What are three goals you would like to be able to accomplish by the end of this course? Be as specific as possible.

For example, If you are currently a teacher, of the tests/assessments that you currently use, which would you be interested in understanding better? Are there any assessment issues that have been puzzling you?

1.

2.

3.

NAME: DATE:

Select all applicable characteristics of a "good" assessment.

1. _____ Assessments should be practical to administer, score, and interpret.

2. _____ Placement tests should identify where the student should be most appropriately placed with respect to a curriculum.

3. _____ cal Language assessments should focus on isolated grammati-forms, eg.: Supply the present tense in each sen-

Metrics

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.

NoDerivatives — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyright without restrictions. Also, The Colombian Apllied Linguistics Journal will allow the author(s) to retain publishing rights without restrictions.